As I discussed last week, new knowledge, not in itself research, is an important outcome of research and, through diffusion and dissemination, a tool for further research.

As I discussed last week, new knowledge, not in itself research, is an important outcome of research and, through diffusion and dissemination, a tool for further research.

GN, meaning to know and beget, with both cognitive and sexual connotations, is one of the most prolific IndoEuropean roots, with numerous forms: lengthened e-grade, GNĒ, o-grade, GNŌ, and zero-grade, GNƎ, which can all be suffixed.

Greek derivatives included γνώμων, one who knows, and therefore an inspector, examiner, interpreter, then a carpenter’s square, and, with its modern English derivative, gnomon, the pointer on a sundial. These meanings were then transferred metaphorically to mean a rule of life or code of regulations. The plural, γνώμονες, meant a horse’s teeth, which indicate its age, and physiognomy is a human face. A gnome is a short pithy statement pathognomonic of a general truth.

Norma in Latin, a carpenter’s square or rule, was cognate with gnomon, perhaps derived via Etruscan; it also meant a standard or pattern of practice or behaviour—hence normal and normative.

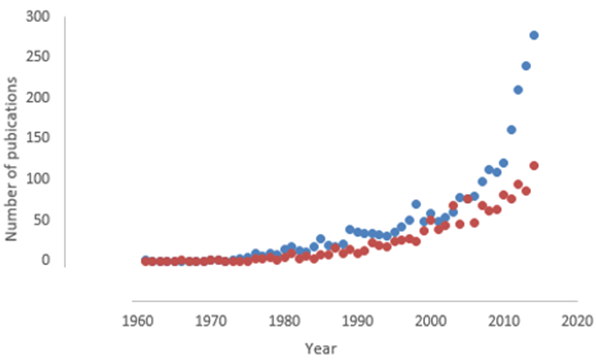

Reduplication in Greek gave γιγνώσκειν, to know or perceive, the noun from which, γνῶσις, meant seeking to know, inquiry, or investigation, giving us gnosis, gnostic, agnosia, anosognosia, diagnosis, misdiagnosis, prognosis, astereognosis, and the terms underdiagnosis and overdiagnosis, currently gaining popularity (see Figure). As I write, the earliest citations for “underdiagnosis” and “overdiagnosis” in the OED are from 1966 and 1971, respectively, from Gastroenterology and the Journal of the Canadian Association of Radiologists. But I have found an earlier instance of both, from 1955, in the British Journal of Preventive and Social Medicine: “The authors’ opinion inclines to the possibility of underdiagnosis of lung cancer rather than to its overdiagnosis in the two bronchitic series.”

Figure. Numbers of publications retrieved by searching for the terms “overdiagnosis” (blue symbols) and “underdiagnosis” (red symbols) in PubMed

In Latin, [g]noscere and cognoscere meant to know, learn, study, from which we recognise cognition and general ignorance. Nobilis meant well known, giving us noble and nobility. [G]narus meant knowledgeable or expert and [g]narrare to tell something you knew about; hence narrate.

Teutonic derivatives change the g in GN to a k, giving German words meaning to know: kennen, erkennen (to know, recognise, identify), and können (to know, be capable, or be permitted); and “ken” is still used in Scotland to mean “know”. “Can” and “cunning” are English derivatives, as is “con”, to know or get to know and hence to study, learn, peruse, or memorise. In “kin”, people you know all too well, knowledge and sex converge. A kindergarten is where you send your children (German kinder) and to kindle means to beget flame. Similarly, “con” has a sexual meaning.

“Know” in “the biblical sense” dates at least from the 12th century. “And Adam knew Eve his wife, and she [begat] Cain”. This trail leads us to gender, generate, pregnant, progeny, genitals, genitive, gentry and jaunty, gentleman, gonad, gonorrhea . . . the list goes on and on. Lectus genialis, the conjugal bed, gives us genial, congenial, and generous.

“Con” is French slang for the female pudenda (also, punningly, petit coin). When Shakespeare shows us Princess Katharine having an English lesson in anticipation of her marriage to Henry V, we see her gentlewoman telling her that a dress in English is a gown, which, in modern versions, she pronounces “coun”, although the First Folio is more explicit—it has “count”. The princess is shocked, especially having also just heard that the English for “pied” is “foot”, reminiscent of the French word “foutre”: “O seigneur Dieu! Ce sont mots de son mauvais, corruptible, gros, et impudique: je ne voudrais prononcer ces mots devant les seigneurs de France pour tout le monde. Foh! Le foot et le coun!”

Elsewhere, Shakespeare plays the same game with “country”. In The Comedy of Errors, Dromio of Syracuse says of a kitchen maid, “a very beastly creature”, who mistakes him for his twin brother, Dromio of Ephesus, “I think I could find out countries in her”. Just before the performance of “The Mousetrap” Hamlet, having asked Ophelia if he might lie in her lap, and having been rebuffed, says to her “Do you think I meant country matters?” Ophelia is coy: “I think nothing, my lord.” And in Cymbeline, one of Filario’s friends, a Frenchman, talks about praising “our country mistresses”, having in mind, no doubt the old French word “cuntré”, from the Latin terra contrata. The Latin word cunnus, pudenda, may have been influenced by “cuneus”, a wedge.

Knowledge makes research sexy.

Jeffrey Aronson is a clinical pharmacologist, working in the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine in Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences. He is also president emeritus of the British Pharmacological Society.

Competing interests: None declared.