Having deconstructed part of the Conservative Party’s 2015 manifesto in last week’s blog, I thought that I ought to extend the favour this week to the Labour Party’s 2015 manifesto.

Having deconstructed part of the Conservative Party’s 2015 manifesto in last week’s blog, I thought that I ought to extend the favour this week to the Labour Party’s 2015 manifesto.

Reading it, I was immediately struck by a phenomenon that I previously described when discussing weasel words—the flexible use of the words “we” and “our”, covering the spectrum from the all exclusive variety (the editorial or royal we, i.e. “I”) to the all inclusive variety (i.e. all of us). Even single sentences illustrate this diversity: “We [i.e. our opponents in the coalition government] are not building the homes we [all of us, or at least those in search of a home] need.” And again: “We [the author(s) of the manifesto] know we [the Labour Party in government] achieve more when we [indeterminate] work together.”

Then of course there is vagueness and ambiguity: “There are some [unspecified people] who believe there is nothing we [the current government? the Labour Party, if elected? all of us?] can do to change things [what things?] for the better.” When I came to read the section on the NHS, I was struck by the way in which the service was personified.

Personification is a rhetorical trope in which animals, plants, natural elements, or abstract ideas are treated as if they had human attributes. In art it refers to symbolic representation of a thing or abstraction by a human figure, as in the personification of health, cleanliness, and hygiene in statues of the goddess Hygeia, daughter of Asklepios. The Latin word persona originally meant a mask, as worn by actors on stage, hiding their faces while they represented a fictional character, an animal, an object, an institution, or some abstract quality. The characters in the cast were collectively known as dramatis personae. Persona could also refer to a gargoyle, a grotesque representation of a face in stone. It then came to mean the representation of a face in a portrait and hence an individual. Personae fictio was the pretence (fictio) that something non-human had a personality—personification.

Persona in Latin was the equivalent of πρόσωπον in Greek, literally close to the eyes or face. Prosopography is the study or description of an individual’s life and career, and can describe a collection of such studies, focusing on the careers and relationships of a particular group in a particular place and time. Prosopolepsy is a preference for a particular person, class, or rank. Prosopagnosia is difficulty in recognising faces. Having a mild form of this, I am on occasion unable to distinguish between two people of similar appearance if I see them at different times, especially in connected places, or to recognise an individual I know, if out of context. Oliver Sacks had a more severe form, as he described in detail in The Mind’s Eye (2010). Sacks’s difficulty went beyond other people’s faces. It extended to buildings and even to himself. “On several occasions,” he wrote, “I have apologised for almost bumping into a large bearded man, only to realise that the large bearded man was myself in a mirror.”

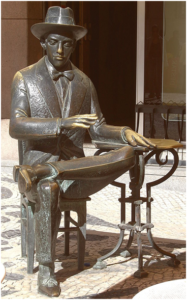

The surname of the Portuguese writer and poet Fernando António Nogueira Pessoa (1888–1935, picture) means “person”. It was not perhaps surprising therefore that a man whose name offered him no more identity than would confirm his own existence should have chosen to publish under a vast number of pseudonyms, which he variously called heteronyms, para-heteronyms, proto-heteronyms, and semi-heteronyms. He even described his own name, Fernando Pessoa, variously as an autonym, heteronym, or orthonym. Pessoa created over 70 personas, each with his own personality and characteristics, not mere alter egos. “Give to each emotion,” Pessoa wrote, “a personality.” His personas included “Ricardo Reis”, a physician who composed odes influenced by the Roman poet Horace.

Image: Personification personified: a statue of Fernando Pessoa outside a Lisbon coffeehouse, A Brasileira

Personification of “our NHS” infests the Labour Party’s 2015 manifesto: “We will start with the promise of investment so that the NHS has time to care. The NHS is struggling with staffing shortages. … We will … restor[e] proper democratic accountability for the NHS. … an NHS under huge strain faces a real threat to its future.” How can the NHS show that it cares, remedy its staff shortages, respond to those who would hold it accountable, or face its future? Who are those behind the mask of personification who will do all that? If the authors of the manifesto didn’t know, or were reluctant to identify them, how could they have achieved what they promised? In short, who are “we”?

Jeffrey Aronson is a clinical pharmacologist, working in the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine in Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences. He is also president emeritus of the British Pharmacological Society.

Competing interests: None declared.