“You want a blood test to make sure that there isn’t a reason why you’re tired?” I ask the patient sat in front of me, checking that I have understood what they have been telling me about for the last five minutes. I now know that they work shifts, have three children under the age of five, and that their mother has recently been diagnosed with cancer.

“You want a blood test to make sure that there isn’t a reason why you’re tired?” I ask the patient sat in front of me, checking that I have understood what they have been telling me about for the last five minutes. I now know that they work shifts, have three children under the age of five, and that their mother has recently been diagnosed with cancer.

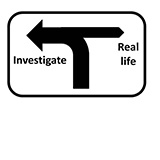

For a split second I realise that I am at a T-junction. The wide road I am standing on swings round to the left. It is signposted, “Investigate.” Off to the right is pot-holed dirt track heading into a dark wood. It is signposted, “Real life.”

One of the many decisions I have to make in this consultation is whether to acquiesce to medicalisation of symptoms which are highly likely to be due to social factors. The alternative is to begin a potentially difficult discussion about how blood tests usually don’t show anything meaningful and that there are plenty of reasons for people, and not just patients to feel tired. Nagging right at the back of my mind is a nebulous swirl of sinister and not-so-sinister conditions that present with symptoms of fatigue. What if, against all odds this patient actually had some pathology?

Standing at the junction, I had managed, in a split second, to have sent out a search party down each and every fork off each of the two routes that stand before me. They wouldn’t, unfortunately, be able to send back reports from the near and far future.

Standing at the junction, I had managed, in a split second, to have sent out a search party down each and every fork off each of the two routes that stand before me. They wouldn’t, unfortunately, be able to send back reports from the near and far future.

“So what do you think, doctor?” asked the patient.

I hoped that I had given the appearance of being as thoughtful as I actually felt. I glanced at the computer screen. It told me that three patients were waiting to see me. I was running late. I hated running late and yet I also felt compelled to do the right thing.

I took a deep breath, “You know, it seems to me that there are plenty of reasons to explain why you feel tired, don’t you think?”

As the consultation ended I couldn’t help thinking that there were many barriers to doing the right thing, practicing holistic medicine that treated (no pun intended) patients as human beings and not just a collection of symptoms and “measurables.” There were pressures to treat numbers, hit targets, interpret which medications and interventions were actually effective and cost-effective. I often have to ignore my dislike for running late; I find the greatest pressure is time. Explaining why an investigation or treatment is not needed is often more lengthy, nuanced, and difficult than simply saying, “Just book a phlebotomy appointment at reception.”

Samir Dawlatly is a GP partner at Jiggins Lane Surgery in Birmingham. He combines clinical practice with being a part time house husband and an interest in social media, as well as publishing poems, essays, and blogs. He can be found on Twitter as @sdawlatly.

Competing interests: I have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and declare the following interests: I am a member of the RCGP online working group on overdiagnosis.

The patient in this blog is not real.