Some of us are driven by personal conviction about our career choice while others succumb to the subtle and not to subtle influence of peer pressure or well meaning parents.

Some of us are driven by personal conviction about our career choice while others succumb to the subtle and not to subtle influence of peer pressure or well meaning parents.

I have a childhood encounter with a lamp post to thank for setting me on the road to becoming a surgeon, when I lost a tooth and shattered the bone above my mouth leading to several years of reconstructive surgery.

My confidence—and willingness to smile in photographs—returned with a replacement tooth and I plumped for a career in dentistry before specialising in maxillofacial surgery, which uniquely combines the disciplines of dentistry and surgery.

“Max fax” is at the radical end of the surgical scale. It can literally involve taking the face and neck apart, including major tissue transplants, and the removal and replacement of cancerous bone, teeth, eyes, and muscle.

A rise in the incidence of head and neck cancers presents a challenging roster of surgical procedures, and I now regularly employ the use of 3-D technology in major reconstructive surgery.

This technology was originally developed in the film industry by pioneering special effects directors such as Steven Spielberg and James Cameron, and its crossover employment in medical science has great potential.

You’d be hard pressed to find another surgeon citing Toy Story or Jurassic Park as seminal influences, but these groundbreaking special effects have proved inspirational, if unorthodox, reference points in my work as a surgeon.

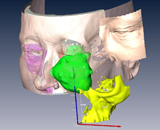

The technology accurately maps 3-D “before and after” models of patients’ heads allowing me to view objects such as tumours from any number of angles, as well conduct “virtual” surgery.

Images are initially gathered via CT and MRI scans and then uploaded into an over the counter software package.

The benefits include greater preoperative planning, reduced theatre times, and the ability to calculate various measurements and incisions involving the removal and replacement of damaged bone and tissue.

I am lucky enough to have honed my computer skills over the years from my initial efforts as a teenager modelling 3-D furniture and fruit to my first surgically applied application repairing a fractured cheekbone.

One of the most recent procedures captured the media’s attention when, during two seven hour operations, myself and a fellow surgeon removed a large tumour including a portion of a patient’s jaw, left eye, and numerous teeth before beginning the painstaking work of reconstructing the damaged area.

One of the most recent procedures captured the media’s attention when, during two seven hour operations, myself and a fellow surgeon removed a large tumour including a portion of a patient’s jaw, left eye, and numerous teeth before beginning the painstaking work of reconstructing the damaged area.

This included removing a portion of leg bone and re-sculpting it into the jaw as well as prepping the jaw for the latter inclusion of dental implants.

The advantage of pre-operative planning meant we could determine the position of the implants in the patient’s iliac crest, scapula, or fibula in virtual space, which saved a lot of guesswork on the operating table.

The next leap in technology will be the use of 3-D surgical glasses with the ability to see through tissues. This will help surgeons to see the microscopic spread of cancerous cells allowing us to more accurately remove affected areas.

I am also hopeful that St George’s Hospital, Tooting, pioneering use of robotic surgery in urology will be expanded to include maxillofacial procedures in the next year.

This, of course, requires considerable training and the challenge for surgeons is finding both the time and technological appetite for more study. It’s always demanding working on the edge of your comfort zone, but that’s where the real change takes place.

Kavin Andi is a consultant maxillofacial and specialist microvascular reconstructive plastic surgeon at St George’s Hospital, Tooting, London.

Competing interests: KA has nothing to disclose.

Patient consent obtained.