There is a long honoured tradition in a number of specialities, and sub-specialities, of knowing The Landmark Trials. The studies that demonstrated that something works or that some method is better than another.

There is a long honoured tradition in a number of specialities, and sub-specialities, of knowing The Landmark Trials. The studies that demonstrated that something works or that some method is better than another.

But Landmark Trials are bunkum.

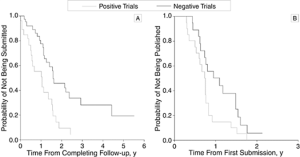

There’s a couple of problems with Landmark Trials though; firstly – the general rule is that the earliest trials in a subject show report much greater effects than later ones. This has been demonstrated in a fair few examples – including this classic from 1998 showing that the in non-significant studies is greater than delay tends to be in significant ones:

(doi:10.1001/jama.279.4.281)

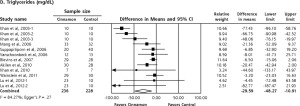

In terms of effects and time, then this ‘cinnamon in diabetes’ review is fascinating – it’s arranges in chronological order of publication:

(doi: 10.1370/afm.1517 – ignore that meta-analytic diamond by the way – it’s meaningless – the I-sq is 84%)

But perhaps the greatest example of why we should destroy the edifice of the Landmark Trial is this huge analysis by the genius of John P. A. Ioannidis, who took about a decade’s worth of studies from major journals that had been cited over 1000 times, and looked to see what the subsequent studies showed. His conclusion was

“Contradiction and initially stronger effects are not unusual in highly cited research of clinical interventions and their outcomes.”

Only 44% of these ‘Landmark’ studies ended up having subsequent studies confirming the size and direction of effect they had found.

Of course, it’s interesting to know what led us to do what we do. But let’s not make the ‘Landmark Trial’ a thing of clinical importance; systematic reviews are what should guide our practice. Landmark trials are just for the historian in us.

- Archi