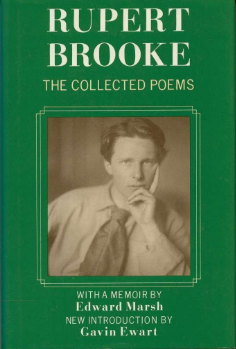

As I noted last week, “spuria”, defined in the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) as “spurious works, words, etc.”, was first recorded in 1918. The word appeared in Rupert Brooke: a Memoir by Sir Edward Marsh, who also edited Brooke’s Collected Poems in the same year (pictures). Commenting in a footnote on Brooke’s use of “your” instead of “you’re” in a letter in which he appointed Marsh his “literary agent or grass executor”, as Brooke put it, Marsh wrote “I hope this note will not start a vain hunt for spuria among [Brooke’s] published poems.” Certainly, no spurious words are attributed to Brooke in the OED.

As I noted last week, “spuria”, defined in the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) as “spurious works, words, etc.”, was first recorded in 1918. The word appeared in Rupert Brooke: a Memoir by Sir Edward Marsh, who also edited Brooke’s Collected Poems in the same year (pictures). Commenting in a footnote on Brooke’s use of “your” instead of “you’re” in a letter in which he appointed Marsh his “literary agent or grass executor”, as Brooke put it, Marsh wrote “I hope this note will not start a vain hunt for spuria among [Brooke’s] published poems.” Certainly, no spurious words are attributed to Brooke in the OED.

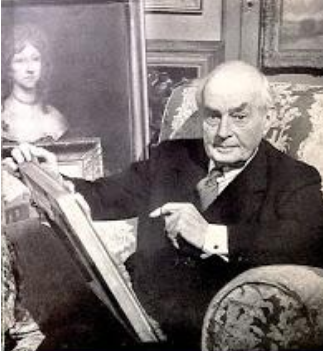

Sir Edward Marsh and a later edition of Rupert Brooke’s Collected Poems (originally published in 1918)

However, several spurious words and spurious meanings of proper words have appeared in dictionaries from time to time. For example, a spurious meaning of the word “imperiality”—“an imperial right or privilege”—was first mistakenly recorded in Webster’s Dictionary of 1828 and copied verbatim into later dictionaries.

James Boswell tells how a woman challenged Johnson to explain why, in his dictionary of 1755, he had defined “pastern” as “the knee of a horse”. Johnson’s reply was typically robust: “Ignorance, madam, pure ignorance.” In the abridged version of 1756 Johnson defined pastern correctly as “that part of the leg of a horse between the joint next the foot and the hoof.”

Truly spurious, i.e. non-existent, words are also recorded in dictionaries. Here are some examples from the current online OED:

- fleingall: “an alleged name of the kestrel”, from a misprint in E Topsell’s History of Serpents, for “steingall”, the German name for the bird; other English words for the kestrel include staniel and stonegall;

- shairl: a misprint for “shawl” in E P Wright’s Animal Life (1879);

- suffarraneous, which the OED merely glosses as a spurious word, supposedly from sub + far (grain or meal) and meaning something related to “[the carriage of] meal or flour to any place to sell”.

In the first edition of the OED, James Murray included about 400 spurious words, identifiable by being enclosed in square brackets, correcting errors that had been perpetrated in other dictionaries—a sort of oneupmanship on the editor’s part. Most of these nonexistent words arose through misprints or through errors or misreadings of copyists or translators. For example, exidemic for epidemic, owing to the similarity between x and p in early handwriting.

One of these, “dentize” was a misreading of the Latin verb “dentire”, to cut teeth, as found in Sylva Sylvarum (1626), in which Francis Bacon wrote how “They tell a tale of the old Countesse of Desmond, who lived till she was seven-score yeares old, that she did Dentire, twice, or thrice; Casting her old Teeth, and others Comming in their Place.” Now humans, and most other mammals, are diphyodonts—they normally have only two dentitions; rodents are monophyodonts—their teeth grow continuously and are never replaced; kangaroos, elephants, and manatees, unique among mammals, and some non-mammalians species, typically fishes and reptiles, are polyphyodonts, animals whose teeth are repeatedly replaced during their lives.

“Third dentition” is often used to describe false teeth. However, there have been well attested reports of true third dentition in humans. Ooë, for example, referred to some reported cases (attributed to delayed eruption of supernumerary teeth) and also described a histological structure that he proposed was the precursor of a potential third dentition in man. Furthermore, studies of the several genetically determined syndromes that are associated with supernumerary teeth have opened up the possibility of stimulating third dentition using gene therapy.

Although many other spurious words, also called ghost words, have arisen through misprints or misreadings, lexicographers have also sometimes deliberately included nonexistent words in their dictionaries, in order to catch out plagiarists. Such words are sometimes called Mountweazels, after Lillian Virginia Mountweazel, a fictitious person listed in the fourth edition of The New Columbia Encyclopedia (1975). The name may have been coined by association with weasel words, defined in the OED as “equivocating or ambiguous words which take away the force or meaning of the concept being expressed”.

Jeffrey Aronson is a clinical pharmacologist, working in the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine in Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences. He is also president emeritus of the British Pharmacological Society.

Competing interests: None declared.