The latest Quarterly Monitoring Report from the King’s Fund surveying NHS trust finance directors reveals deepening pessimism about local finances and concern about the outturn for the current financial year. New NHS inflation figures from NHS Improvement reveal the true extent of the financial pressures facing the NHS this year and up to 2020/21.

The latest Quarterly Monitoring Report from the King’s Fund surveying NHS trust finance directors reveals deepening pessimism about local finances and concern about the outturn for the current financial year. New NHS inflation figures from NHS Improvement reveal the true extent of the financial pressures facing the NHS this year and up to 2020/21.

How much money the NHS has been allocated over the next few years is a somewhat contested fact. It shouldn’t be of course; how much the government has decided to spend on healthcare should be —in one sense at least—an uncontroversial figure. But since the spending review last November, the increase in NHS funding by 2020/21 has variously been announced as “an additional £10 billion,” “a further £8 billion,” and, for 2016/17, “the sixth biggest increase in its history.”

We arrive at a very different assessment for 2016/17, as Adam Roberts of the Health Foundation and I illustrated in our analysis of how this year’s NHS budget compares historically. But the first two figures are correct—albeit in their own narrowly defined terms. They rely partly on stretching the boundaries of the spending review (the £10 billion includes a £2 billion increase in 2015/16 decided before the spending review was published, for example). They also count increases just for NHS England, rather than for the whole of the NHS, and—unusually—use 2020/21 as the base year for calculating real funding changes.

The measure of inflation used to calculate the real changes in funding for all these figures is the GDP deflator. This is not controversial, and is the way public spending figures are deflated to provide real figures across government on a like for like basis.

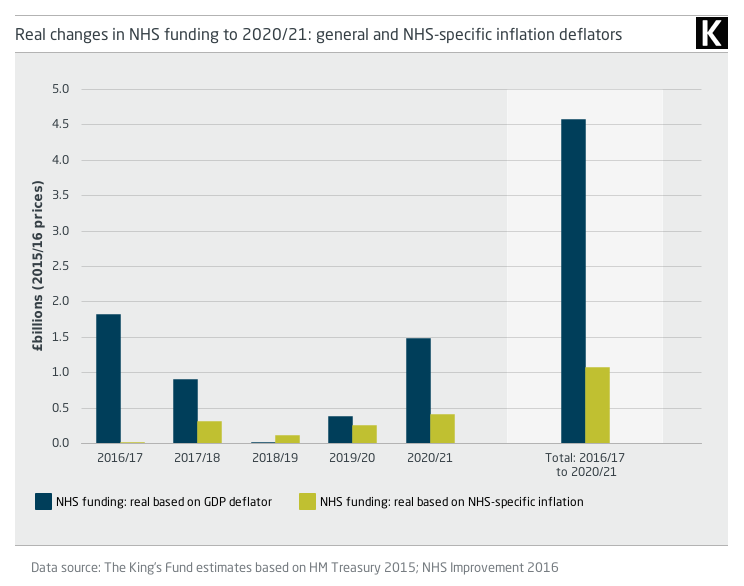

But the GDP deflator is an average measure of inflation across the whole economy; the actual inflation experienced by the NHS will be different given its particular inputs: doctors, managers, needles, drugs etc. Importantly, it is the NHS specific measure of inflation that really counts when it comes to assessing the actual financial resources available to the NHS. And usefully, forward estimates of changes in unit costs for the NHS are produced by NHS Improvement.

NHS Improvement’s latest economic assumptions suggest that NHS specific inflation will be 3.1% this year—double the Treasury’s current estimate of 1.5% for the GDP deflator. This NHS specific rate of inflation is enough to perfectly wipe out this year’s cash increase of £3.6 billion, as all of this is likely to be absorbed by higher staff pay, pay drift and increases in the unit costs of drugs, capital, and other operating costs.

As the chart below shows, on the basis of NHS Improvement’s new inflation forecasts, the overall real increase for the NHS by 2020/21 will be just £1.5 billion and an increase averaging around 0.2% per year.

If NHS Improvement’s inflation estimates turn out to be correct (and they will be subject to revision), it is not hard to discern a key reason for finance directors’ views that this year is going to be exceptionally difficult. Despite an upfront financial rescue package of £1.8 billion, our latest survey suggests that just over half of all NHS trust financial directors forecast a deficit this year—including 69% of acute trusts.

Looking forward, NHS inflation adjusted funding in 2017/18 amounts to an increase of only £313 million—equivalent to less than one day’s running costs for the NHS. Perhaps it’s not surprising then that nearly two thirds of trust financial directors say they are “fairly or very concerned” about balancing their books in the next financial year.

John Appleby is the chief economist at the King’s Fund.

This blog first appeared on the King’s Fund website.