Dr Paul Bowie is programme director for safety and improvement at NHS Education for Scotland. Twitter: @pbnes

“Checking” is endemic in healthcare the world over. It is a routine everyday activity in all care settings and is fundamental to maintaining patient safety. Checking tasks go well in the great majority of cases and do contribute to a successful outcome for the patient. However, sometimes they do not, and this may lead to things going wrong that contribute to patient safety incidents – circumstances where patients could have been or were harmed. Unfortunately some of these incidents can and do have a devastating impact on the wellbeing of patients and families, as well as the care professionals involved.

Minimising the risks of such occurrences is obviously a major safety priority. Even so, this can be very difficult to achieve given the sheer complexity of care systems and the everyday constraints that care teams often work within (eg high workloads, increasing patient demand, and limited resources). The skill and dedication of care professionals in constantly coping and adapting to these ever changing circumstances convincingly explains why things normally go well for patients, but also why sometimes they do not (see the work of Erik Hollnagel or Sidney Dekker for example).

The use of “checklists” is promoted as one approach to standardising working practices to make care systems more reliable and contribute to patient safety.[1] A checklist is a cognitive tool that may help care teams to ensure that safety critical tasks (including communicating effectively with each other) are actually carried out. Perhaps the most well known example in healthcare is the WHO Surgical Safety Checklist which is now mandated in over 150 countries worldwide.[2]

Barriers to checklist use

The safety checklist is often seen as a simple, practical solution – even a panacea – in making sure that highly important patient care tasks are actually performed and performed on time.[3,4] The evidence base, however, shows a different reality.[3,5-9] Checklist adoption by staff groups and subsequent impacts on enhancing patient safety are fairly mixed. In some ways this is no great surprise. In the risk management world, the “hierarchy of intervention effectiveness” rates human behaviour dependent interventions such as checklists, doublechecks, and reminders towards the bottom of its scale.[10]

A range of reasons for this are now apparent. Prime among them is that the checklist can be viewed as an inadequate “technical fix” to what is a “complex socio-cultural problem”. In other words, individual “checking” behaviours and intentions are influenced by the “social group” that people belong to, as well as local healthcare practices, values, beliefs, and traditions. Therefore, adoption is often dependent on how seriously the issue of “checking” is taken within a team or organisation, particularly in complex and dynamic working environments. Potential users may also resist or feel threatened by checklists because they are perceived to replace their expertise or decision making, or oversimplify the complexity of work.

Checklist success factors

On the other hand, checklist success is associated with a number of important factors in combination; it will have limited impact as a solo intervention. Firstly it needs the commitment and the support of healthcare leaders and local promotional champions. Success is also more likely where step by step instructions for simple or straightforward technical tasks are necessary and where staff already know that variations in checking performance exists. There is also the fact that reliance on human memory is a problem in a busy working environment.

Importantly, any checklist should also be flexible enough to enable users to apply “common sense” judgements, otherwise it will be considered an irritation and remain unused. Checklists that are externally imposed and lack adaptability to suit local contexts can struggle to be fully accepted and implemented effectively. Ultimately, it should have a greater chance of adoption and sustainability where there is frontline consensus that checklist use is highly relevant, that it is feasible to use routinely, and is an improvement on how work is currently done.

A safety checklist for general practice?

So, given all that we know about checklists and their impacts in secondary care, why embark on such a development for the UK general practice setting?

Well, firstly there is a potential “checking problem” in general practice. This is not at all surprising given workload pressures, the complexity and uncertainty of care, and the volume of checks that are required to be carried out on a daily, weekly, monthly, quarterly, and annual basis to help the team run the practice safely and efficiently. General practice managers and nurses in particular will all attest to that!

Although the safety evidence base is limited in this area,[11] most who work there will be able to recall different incidents happening (and recurring) that involved a failure to check safety critical issues, or (probably more likely) when necessary checking tasks were not performed on time. Examples would include: patients with the same name being mixed up, emergency drugs being out of date when required, employing clinicians who are not currently registered to practise, emergency equipment not working or adequately calibrated, IT systems not being routinely backed up, and so on.Secondly, although numerous safety checks are always carried out, it often seems to be done in an ad hoc manner – that is, there is a lack of standardised, timely and consistent checking processes in many general practices. Again this is unsurprising. Most practices will have limited knowledge or experience of taking a ‘systems approach’ to identifying and routinely checking safety issues of importance, measuring performance and implementing any necessary improvements.

As a starting point to understanding this issue more clearly, NHS Education for Scotland worked closely with GP managers, nurses, and doctors to identify and prioritise a comprehensive range of safety hazards across the whole working environment (box 1). This in turn informed the design of an integrated checklist; although we’ve labeled it a “checklist” it would probably be more accurately defined as a global checking system.[12] The consensus is that it would need to be applied at least every four months. Pilot testing estimated that this would take around two hours to complete, which was deemed feasible and is arguably more manageable when compared to some checking processes that are in place.

A way forward?

It is perceived to be a very necessary intervention by those involved in the initial study, with many frontline practitioners and safety improvement decision makers, who have since attended related workshops or conference presentations, also agreeing. The RCGP clearly recognises its potential value and have included it in their recently launched national patient safety toolkit.[13]

To some extent the most straightforward part has been achieved. The real difficulty comes in developing the checklist further to make it easier to use and implement in busy practices – this is currently under discussion with colleagues in Healthcare Improvement Scotland. The idea of using a tablet or similar device to assist users is being given serious consideration, although introducing another technology potentially raises a set of other problems.

Importantly, how the checking process is designed, promoted, implemented, used, and supported as a patient safety intervention will largely determine its fate – we will need to understand if and how it works and why. If most GP teams believe it to be helpful and an improvement on how everyday work is currently carried out then there is hope for success. However, if most believe it to be a hindrance then…

Suggested reading:

- Catchpole K and Russ S. The problem with checklists. BMJ Qual Saf 2015;24:545-549 doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004431

- Bosk CL, Dixon-Woods M, Goeschel CA, et al. The art of medicine: reality check for checklists. Lancet. 2009;374: 444–5.

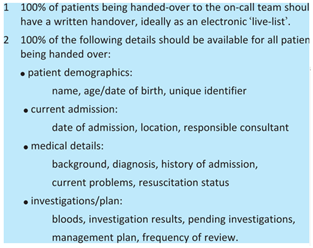

Box 1. Selected examples of identified potential hazards in the general practice work environment which informed development of checklist content

| Safety Domains

(sub-categories) |

Examples of potential hazards:

Patient, GP team members, and practice organisational outcomes

(eg quality, safety, health, wellbeing, performance) |

| Medication management(controlled drugs; emergency drugs and equipment; prescriptions and pads; vaccinations; all other drugs) |

- Lack of in-date stock may lead to inability to treat acutely ill patient

- Lack of necessary emergency drugs or out-of-date emergency drugs can lead to patient safety being compromised, for example, adrenaline for anaphylaxis.

- Protects these prescription-related items from potential theft which can lead to unauthorised prescriptions of high risk drugs being dispensed to vulnerable patients or members of the public who may harm themselves as a result

- Safe and secure keeping is necessary to prevent theft and misuse which could harm patients and members of the public

|

| Housekeeping

(infection control; stocking of clinical rooms; confidential waste; clinical equipment maintenance) |

- Staff and patients, including children, obtaining a needle stick injury from overfilled “sharps” bins

- Patients at risk of infection from spilled hazardous waste on clinical surfaces/equipment

- Patients and staff at risk of cross-contamination from blood/bodily fluids

- Risk of cross-infections from, for example, people, equipment and clinical surface areas

- Breaches of patient confidentiality can impact on patient safety via patients’ suffering psychological harm from knowing their medical history has been disclosed publically

|

| Information systems

(business continuity plan is up to date; verifiable back-up of all IT systems; data protection; record keeping) |

- Can impact on how safe patient care is delivered in an emergency situation e.g. electrical outage to the practice affecting IT systems and how to manage and deliver care in such a situation

|

| Practice team

(registration checks; CPR and anaphylaxis training; induction processes; access to patient safety-related training) |

- [All clinicians are registered with professional regulators]… patient safety-critical checks which protect the local patient population and the practice as an organisation

|

| Patient access and identification

(access information for patients; standardised patient ID verification) |

- Numerous significant events in general practice are related to mix-ups over patient identification leading to patient’s being subjected to unnecessary treatments, hospital visits and investigations, and breaches of confidentiality which can cause avoidable physical and emotional harm

|

| Health and safety

(building safety and insurance; environmental awareness; staff health and wellbeing) |

- Hazards in the workplace which are not identified and attended to can lead to harm (e.g. a patient sustaining a head injury from walking into a low lying light)

- Staff can be subject to abuse, anger, threatening behaviour and violence and should be trained to manage these situations to protect the safety and wellbeing of themselves and patients.

|

References

- Haynes AB, Weiser TG, Berry WR, et al. . A surgical safety checklist to reduce morbidity and mortality in a global population. N Engl J Med 2009;360:491–9.

- World Health Organisation. Implementation of the surgical safety checklist. WHO, Geneva; 2008.

- Catchpole K and Russ S. The problem with checklists. BMJ Qual Saf 2015;24:545-549 doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004431.

- Bosk CL, Dixon-Woods M, Goeschel CA, et al. The art of medicine: reality check for checklists. Lancet 2009;374: 444–5.

- Fourcade A, Blache J-L, Grenier C et al., Barriers to staff adoption of a surgical safety checklist. BMJ Quality & Safety 2011 doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2011-000094.

- Hillgoss B & Moffat-Bruce S. The limits of checklists: handoff and narrative thinking. BMJ Qual Saf 2013;doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2013-002705.

- Ko HCH, Turner TJ, Finnigan M. Systematic review of safety checklists for use by medical care team in acute hospital settings – limited evidence of effectiveness. BMC Health Services Research 2011;11:211.

- Gillespie B, Marshall A. Implementation of safety checklists in surgery: a realist synthesis of evidence. Implementation Sci 2015, 10:137.

- Russ SJ, Sevdalis N, Moorthy K, Mayer EK, Rout S, Caris J, et al. A Qualitative Evaluation of the Barriers and Facilitators Toward Implementation of the WHO Surgical Safety Checklist Across Hospitals in England Lessons From the “Surgical Checklist Implementation Project”. Ann Surg 2015;261(1):81–91. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000000793.

- Caffazo JA, St-Cyr. From discovery to design: the evolution of Human Factors in healthcare. Healthcare Quarterly 2012:(Vol.15 Special Issue);24-29.

- Health Foundation. Evidence scan: levels of harm in primary care (2011). Available at: http://www.health.org.uk/publications/levels-of-harm-in-primary-care/ [Accessed 25th September 2015]

- Bowie P, Ferguson J, Macleod M, Kennedy S, de Wet C, McNab D, Kelly M, McKay J, Atkinson S. Participatory design of a preliminary safety checklist for general practice. Brit J Gen Pract 2015; 65(634) DOI:10.3399/bjgp15X684865

- Royal College of General Practitioners. Patient Safety Toolkit for General Practice. http://www.rcgp.org.uk/clinical-and-research/toolkits/patient-safety.aspx [Accessed 11th November, 2015]

As comfortable as we have become over the last eight months, there are still times where we are reminded that we have a long way to go. As a junior doctor you often feel powerless to execute change yourself. Sometimes you feel as if you are just a small cog in a giant wheel of change that is rusty and stuck; a wheel crying out for oil like the Tin Man from “The Wizard of Oz”.

As comfortable as we have become over the last eight months, there are still times where we are reminded that we have a long way to go. As a junior doctor you often feel powerless to execute change yourself. Sometimes you feel as if you are just a small cog in a giant wheel of change that is rusty and stuck; a wheel crying out for oil like the Tin Man from “The Wizard of Oz”.