Blog by Aanya Ravichander

Metaphors may be as necessary to illness as they are to literature, as comforting to the patient as his own bathrobe and slippers.

—Anatole Broyard1

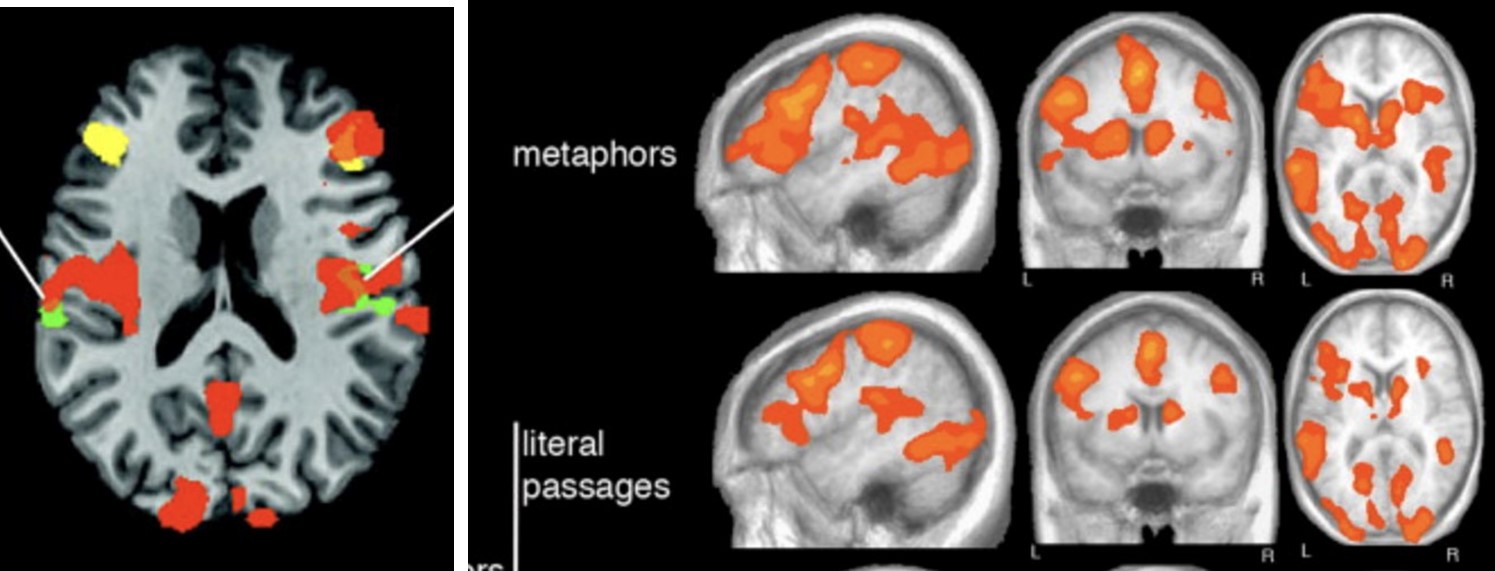

Studies show that patients communicate better with physicians who use metaphors.2 Metaphors not only subconsciously influence our thinking, they determine how we approach obstacles, conceptualize abstract concepts, and find solutions.3 One well-known medical example examines how framing cancer as a journey alters the way patients perceive their illness.4 Other studies have reinforced that metaphorical language activates more regions of the brain than literal language does (fig. 1).5

As part of an ongoing research project, I conducted a case study to investigate the use of metaphors within pediatric practices for the care and treatment of sexual abuse survivors. I interviewed three medical professionals, including two child abuse pediatricians and a Trauma Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT) certified psychologist. Treating such a vulnerable population makes careful language use even more relevant and applicable to improved clinical outcomes. My aim was to draw attention to the utility of language tools in clinical and healthcare settings rather than to make generalized claims about the usage of metaphors in the treatment of sexually assaulted pediatric patients.

At the onset of the interview process, the health care professionals explained that they did not use many metaphors in their clinical practice, primarily because protocols required them to be succinct and precise. However, as the interviews progressed, they described several metaphors indispensable to patient communication, care, and treatment in their clinics. Upon further reflection, the care providers acknowledged that metaphors are intertwined in the language they use to provide care. The clinicians were surprised at the degree to which they use metaphors in their everyday practice and that they were doing so unconsciously.

The metaphors were varied and typically had a specific rationale pertinent to the patient’s age and situation. A “box of memories” was one of the most effective metaphors because it enabled the separation of emotion from trauma. The children had agency to choose what stays in and what comes out of the “box,” exerting control over the details of the abuse that they were ready to share. Other metaphors reassured the children that therapy could be beneficial in their situation. For example, “monsters in the basement,” a “giant rock,” or a “ping pong ball in your head” allowed them to visualize their trauma and relate it to something that they see in everyday life. Metaphors, therefore, enabled patients to communicate their feelings more clearly with their providers and navigate an unruly and unmanageable situation.

The health care professionals also used metaphorical framing to express difficult topics in contexts relatable to a pediatric population. Diagnostic uses included helping children open up about their experiences, for example, comparing pediatric trauma to a “scraped knee” that requires washing out and not just a Band-Aid. And since treatment often requires conceptualizing a “trauma hierarchy” that needs to be unpacked, step by step, some providers had children imagine “climbing a mountain.”

Overall, the interviewed care professionals employed metaphorical language to help these patients process and express their trauma. Such attentive language aids the continuation of care and helps shepherd patients through the difficult process of navigating trauma. More importantly, metaphors allowed pediatric patients to be more comfortable discussing their care.

Metaphors aid clinicians to establish rapport, enable in-depth patient-physician conversations, and serve as therapeutic aides. Language tools incorporating metaphors may also humanize therapeutic care for patient populations, alleviating the typically sterile clinical experience. Figurative language tools can thus have broad applications in many patient care settings well beyond the specific pediatric population I have discussed in this paper, although further research is required to substantiate the clinical utility of metaphors in practice.

Aanya Ravichander is an undergraduate at Emory University majoring in Human Health with a minor in Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies. She is interested in pursuing a career in medicine with a focus on pediatric neurological conditions, adolescent medicine, and women’s health. She is passionate about advocacy for survivors of sexual violence and unearthing areas of research in the intersections of clinical medicine and humanities.

References

[1] Intoxicated by My Illness and Other Writings on Life and Death (New York: Ballantine Books, 1993).

[2] David Casarett et al., “Can Metaphors and Analogies Improve Communication with Seriously Ill Patients?” Journal of Palliative Medicine 13, no. 3 (2010): 255–60. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2009.0221.

[3] Paul H. Thibodeau and Lera Boroditsky, “Natural Language Metaphors Covertly Influence Reasoning,” PLoS ONE 8, no. 1 (2013): e52961. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0052961.

[4] Rose K. Hendricks et al., “Emotional Implications of Metaphor: Consequences of Metaphor Framing for Mindset about Cancer,” Metaphor and Symbol 33, no. 4 (2018): 267–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926488.2018.1549835.

[5] Valentina Bambini et al., “Decomposing Metaphor Processing at the Cognitive and Neural Level through Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging,” Brain Research Bulletin 86, nos. 3–4 (2011): 203–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainresbull.2011.07.015.