Article Summary by Perseverence Madhuku

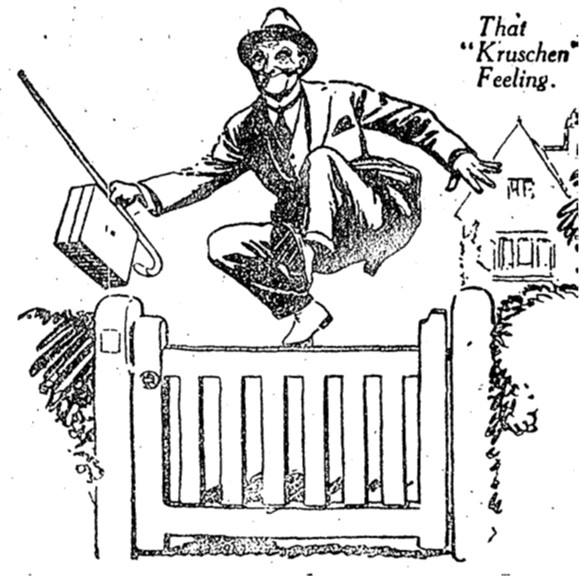

How did exhaustion in British colonies become a medical problem to be fixed, remedied, and eradicated? In the first half of the twentieth century, Kruschen salts, a laxative and diuretic tonic, circulated in Britain and its colonies. It was advertised as a cure for a range of diseases and everyday problems of modern life, including gout, rheumatism, tiredness, weight, eczema, depression, nervousness, anxiety, kidney disorders, constipation, and lumbago. Kruschen salts were manufactured and distributed by the oldest British chemists, Griffiths Hughes Company, established in 1754, and sold at 1s. 6d. Across the British empire, the company established networks of chemists to distribute the salts among white families. From a medical humanities perspective, the most intriguing aspect of Griffiths Hughes’s advertising campaign for Kruschen salts was the claim to alleviate exhaustion, anxiety, and fatigue. Their advertisements promised renewed bodily vigour and mental alertness so as to “work unweariedly without fear of getting tired.”1

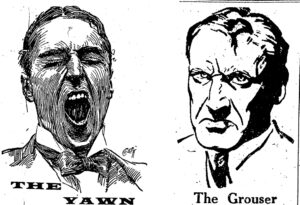

Behind these fantasies for curing tiredness were significant societal transformations that made exhaustion a topic of interest. Kruschen salts claimed to give people a cheerful view of things in the context of colonial expansion and the First World War. In settler colonies with large white communities, such as Southern Rhodesia, South Africa, and Kenya, Kruschen salts found fertile markets because there was a constant fear of nervous degeneration and depletion of energy (real and imagined). White families worried not only about exposure to new tropical environments, popularly known as the “white man’s grave,”2 but also about entanglements with indigenous societies. Tropical environments were thought to breed degenerative and lazy people, in contrast to the strong and manly individuals produced by temperate zones. Medical texts, guidebooks, and promotional material teaching Europeans how to survive in tropical environments reflect these anxieties about degeneracy. Exhaustion became a medical problem to be diagnosed at a time when the body was required to do more for the empire. Thus, Kruschen salt advertisements were embroiled in the language of the empire because “mental and bodily fitness is a state which every man and woman owes to the empire.”3 Frowning, yawning, dozing, and being humourless were all pathologized as unnatural signs of the body demanding proper medicine to eliminate impurities. One advertisement warned against yawning: “…whenever you feel the urge to yawn, commence a Kruschen course; the Kruschen habit is prevention.”4

These cures also reflected dominant conceptions of gender, as they claimed to cure “attacks of housewife nerves”v associated with household chores that were increasingly turning women into rebellious beings. The advertisements encouraged women to use Kruschen salts to tame the nasty tempers caused by exhaustion from household responsibilities. Those who used Kruschen salts looked “alive, happy, healthy and pleased with life,”6 which fit into notions of domesticity that encouraged women to be content with the private sphere rather than look for jobs outside the household.

The promotion of the salts went hand in hand with the growth of print media. The advertisements were appealing, giving people the impression that if they were exhausted, they were ill and could only be cured by proprietary medicines. One declared, “the body is like an orchestra. When badly conducted, away goes the harmony. The body needs a proper conductor to keep its functions in tune. What your body needs is a daily dose of Kruschen salts.”7 Positive testimonials abounded, perhaps by people who had never tasted the salts but desired the prestige of signing their names in print. In South Africa, one doctor complained about the advertisements’ misleading words and illustrations, arguing that certain problems were natural, thus disputing the medicalization of ordinary life. In the United States, the Federal Trade Commission banned Kruschen salts and other proprietary preparations sold by the Griffiths Hughes Company for fraudulent advertising and unfair trade practices, i.e. for “misleading and deceiving the public.”8 However, the salts continued to circulate in the colonies where regulatory regimes were weak.

Among the metaphors associated with burnout in modern life was an image implying the possibilities of regeneration. However, this regeneration of the body was in no way premised on getting enough rest but on taking the miraculous salts because “every hour you are unfit is a wasted hour.”9 The salts expelled “the waste matter that clogs and produces depression and fatigue, purifying and refreshing the blood, priming you in every fibre of your being with a tingling sense of vitality and joyous energy.”10 These advertisements transformed exhaustion into a new category of illness, frequently claiming that it was not overwork that caused fatigue but poison in the blood.

Contextualizing early twentieth-century exhaustion cures helps us understand how individual bodies connect to broader societal transformations. Kruschen salts advertisements transformed what it meant to be exhausted, categorizing this state as a form of sickness to be treated. This rhetorical history should inform our understanding of exhaustion today. The condition of being drained at an individual level is still fertile ground for pharmaceutical companies who might want to take advantage of societal developments to both shift the public’s attention away from the root causes of human problems and medicalize every aspect of life in order to create markets for new products. Sighard Neckel et al. characterised the twenty-first century as “an age of exhaustion.”11 We have seen a massive expansion of markets all over the globe selling antidepressants and antifatigue medicines, making exhaustion an exclusively medical problem.

Perseverence Madhuku is a PhD candidate in the Department of African History at the University of Bayreuth in Germany. She is a DAAD-funded scholar and a member of the Bayreuth International Graduate School of African Studies (BIGSAS). Her research interests lie in the histories of medicine, health interventions, and medical technologies in Africa.

References

[1] The Bulawayo Chronicle, January 28, 1922.

[2] The idea that Europeans in tropical climates suffered physical debilitation. This image was pervasive in the writings of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century travellers, explorers, and philosophers who, due to high mortality rates experienced by Europeans in West Africa, believed that Europeans were racially incapable of surviving in African environments. See Phillip Curtin, “The White Man’s Grave: Image and Reality, 1780-1850,” Journal of British Studies 1, no.1 (November 1961): 94-110, https://www.jstor.org/stable/175101.

[3] The Graphic, January 4, 1919.

[4] Rhodesia Herald, November 17, 1922.

[5] The Bulawayo Chronicle, December 23, 1922.

[6] The Bulawayo Chronicle, December 23, 1922.

[7] The Bulawayo Chronicle, September 24, 1921.

[8] Federal Trade Commission Decisions: Findings, Orders and Stipulations, June 1933 to April 1934, vol. 8, (United States: Washington, 1935), 486, https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/commission_decision_volumes/volume-18/vol18.pdf.

[9] The Graphic, January 4, 1919.

[10] The Sketch, December 12, 1924.

[11] Sighard Neckel et al., eds., Burnout, Fatigue, Exhaustion: An Interdisciplinary Perspective on a Modern Affliction (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017) 1.