Film Review by Khalid Ali, film and media correspondent

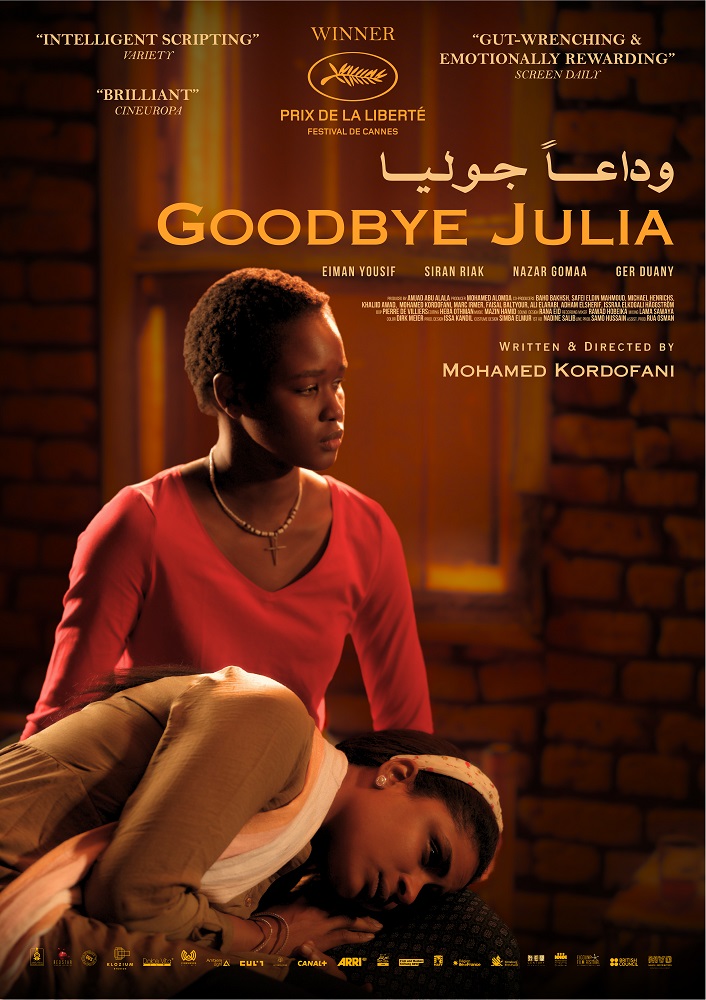

Goodbye Julia (Mohamed Kordofani, Sudan, 2023), screening on 14th and 15th October at the London Film Festival, https://whatson.bfi.org.uk/lff//online/default.asp?BOparam::WScontent::loadArticle::permalink=goodbye-julia-lff23

Winner of the Freedom Prize, Un Certain Regard, Cannes Film Festival 2023.

Alert: this review contains spoilers

The riots, looting, and violence that erupted in Khartoum in 2005 following the death of John Garang in a helicopter crash after only 3 weeks of acting as Sudan’s Vice President comprise the opening scenes of ‘Goodbye Julia,’ a film that delves deeply into the longstanding tensions and mistrust between Northern and Southern citizens of Sudan. During the ensuing demonstrations, Mona (Eiman Yousif), a rich Muslim Northern woman, while driving her car hits Daniel (Louis Daniel Ding), a young Southern boy, and flees the accident scene. Daniel’s father Santino (Paulino Victor Bol) chases Mona in his motorbike and ends up confronting Akram (Nazar Gomaa), Mona’s husband. The heightened emotions that prevailed at the time lead to a tragic ending where Santino is shot dead by Akram. The police force, mostly Northern Sudanese, collude with Akram in dismissing any criminal investigation, and hurriedly close the case as one of ‘self-defence’ against a ‘barbaric Southern slave’. Ridden with guilt, Mona searches for Santino’s family. When she ultimately finds them, she offers the wife Julia (Siran Riak), and her son Daniel shelter, and she employs Julia as a maid in her house. Mona also pays for Daniel’s (old Daniel played by Stephanos James Peter) education in a private school and encourages Julia to join a Christian college to further her own education.

The riots, looting, and violence that erupted in Khartoum in 2005 following the death of John Garang in a helicopter crash after only 3 weeks of acting as Sudan’s Vice President comprise the opening scenes of ‘Goodbye Julia,’ a film that delves deeply into the longstanding tensions and mistrust between Northern and Southern citizens of Sudan. During the ensuing demonstrations, Mona (Eiman Yousif), a rich Muslim Northern woman, while driving her car hits Daniel (Louis Daniel Ding), a young Southern boy, and flees the accident scene. Daniel’s father Santino (Paulino Victor Bol) chases Mona in his motorbike and ends up confronting Akram (Nazar Gomaa), Mona’s husband. The heightened emotions that prevailed at the time lead to a tragic ending where Santino is shot dead by Akram. The police force, mostly Northern Sudanese, collude with Akram in dismissing any criminal investigation, and hurriedly close the case as one of ‘self-defence’ against a ‘barbaric Southern slave’. Ridden with guilt, Mona searches for Santino’s family. When she ultimately finds them, she offers the wife Julia (Siran Riak), and her son Daniel shelter, and she employs Julia as a maid in her house. Mona also pays for Daniel’s (old Daniel played by Stephanos James Peter) education in a private school and encourages Julia to join a Christian college to further her own education.

Mona’s apparent ‘acts of kindness’ sow the seeds of friendship and understanding between the two women. Over the course of six years, Julia becomes Mona’s confidante, both women sharing the intimate details of their respective traumas living in a patriarchal society. Julia matures into a confident, resilient, politically aware woman when she befriends Ager (Ger Duany), an activist in Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA). Ager and his movement champion the referendum of self-determination and separation of the predominantly Christian Southern Sudan from the mostly Muslim Northern Sudan.

When eventually Mona’s long-hidden secret of being responsible for Santino’s death comes the surface, their suddenly fragile friendship is put to the test. However, Mona and Julia’s six years of bonding and camaraderie not only endure, but powerfully demonstrate how women can act as ‘catalysts for change’. By the end, the inevitable, sad parting of the two women mirrors the separation of South Sudan from Sudan, as declared on 9th July 2011.

In this film writer/director Kordofani considers in all its complexity, the discourse of shame, secrecy and silence experienced by internally displaced and refugee women. In so doing, he thoughtfully dissects the overlapping roles of culture, gender, class, and ethnicity in Sudan. In Kordofani’s words: “The film attributes the separation of South Sudan to long-held discriminatory attitudes and practices of Northerners grappling with their cultural and religious identity crises.”

Understanding what happened in Sudan in 2011 and preserving what remains of its unity requires an honest appraisal of the region’s social injustice, oppression, misogyny, and tribal and religious racism. Kordofani again: “The war in South Sudan was a consequence of all these afflictions”. Amjad Abu Alala, film producer, comments further: “Our film is a cautionary tale exposing bigotry and racism against Southerners. Similar practices were the underlying reasons behind the genocide of Sudanese in Darfur, a crime that is still happening to this day. As film makers, we must expose such ills of our society before it is too late, and Darfur ends splitting from Sudan”.

Examples of discrimination and social prejudices against Southerners are to be found throughout the film: Mona insisting that Julia and Daniel use different cutlery; Akram dismissing Julia as a ‘sexually promiscuous Southern woman’; and their neighbour frequently referring to Southerners as alcoholic slaves whose lives are worthless. Kordofani himself lived through some of these incidents as a child: “I was raised in a home where servants’ cutlery was labelled with a red paint to ensure that they are not mixed with household members’ cutlery. Such practices were not frowned upon, they were legitimised as ‘normal’. My father often used the term ‘slave’ and washed his hands after shaking hands with Southern people even though he was one of the most pious and generous men. I loved my father and dedicated the film to his memory as a call to reject and abandon such discrimination”.

Kordofani hopes that Goodbye Julia will inspire its audience to question and challenge themselves, to perceive matters differently, or at least to appreciate that ‘things can be grey sometimes’. He adds: “Julia is neither a saint nor a villain. She went along with Mona’s lies, fully knowing Mona’s motivations, to make a better life for herself and her son. She manipulated Mona’s guilt to her advantage. She is an ordinary fallible character doing wrong things because she is forced to do them as a victim of her society and circumstances. I empathise with all the film characters. Even Akram has a humanitarian side alongside his racist and misogynistic traits”. On a wider scale, Kordofani hopes that the film will attract global attention to what is happening currently in Sudan. There is still an ongoing, escalating tragedy of death and violence perpetuated by the military and the militia rapid support forces who continue to fight each other for riches and power while innocent citizens are paying the price.

The quality of authenticity in the acting of Eiman Yousif and Siran Riak (both non-professional actresses), as Mona and Julia respectively, is a highlight of the film, and a testament to the director’s skills. Kordofani concludes by saying: “The film is my way to say that we need to break the cycle of violence by reconciling as people, otherwise war will never stop. True reconciliation comes from understanding and reflecting on our most painful memories”. The poignant words of the song at the film finale, written by Mohamed Hamid and composed by Mazin Hamid, sum up the hope that despite the separation, joyful memories can still create points of connection among us as human beings, irrespective of our cultural and ethnic differences.

“Take with you all the memories and my meagre apologies.

Just leave me with your smile in my mirror”