Blog by Susanne Lundin

In this second part of a two-part series on the role of ethnology as a humanistic discipline, we look closely at ethnological methods. We saw in part one how a nineteenth-century pregnant farmer’s wife in a Swedish parish placed an axe under her marital bed, hoping to influence the sex of her child. Studying objects such as Hulda’s axe (and today’s ultrasound machines) is one of several qualitative ethnological methods. Other qualitative approaches include interviewing community members, observing participants in their natural environment, and, more recently, studying digital communities (netnography). Quantitative methods such as questionnaires and statistical analyses often complement qualitative approaches (the Folklife Archives housing Hulda’s story included questionnaires). Ethnologists coordinate a patchwork of methods to study how people’s lives are embedded in their social milieu.1

Ethnological Patchwork

The term bricolage, a patchwork technique, describes ethnology’s overall methodology.2 Bricolage allows ethnologists to examine culture in broad and deep ways. Questionnaires and surveys reach a wide public, while interviews uncover nuanced views that may warrant further study. For example, ethnologists polled one thousand individuals in Sweden to gauge their attitude towards organ and cell transplants from animals, or xenotransplantation.3 Most Swedes had a positive opinion of the procedure. At the same time, their free-text comments indicated fears about the procedure’s risks. One participant wrote, “of course you don’t want to die if your heart doesn’t work or your kidney gives out, you grasp at the last straw, but this thing with animals in the body makes me insecure.” Another stated, “I’ve heard that the genetically modified pigs carry some kind of virus similar to HIV, but the researchers don’t know what the situation is … so maybe we’re not supposed to get involved in this.”

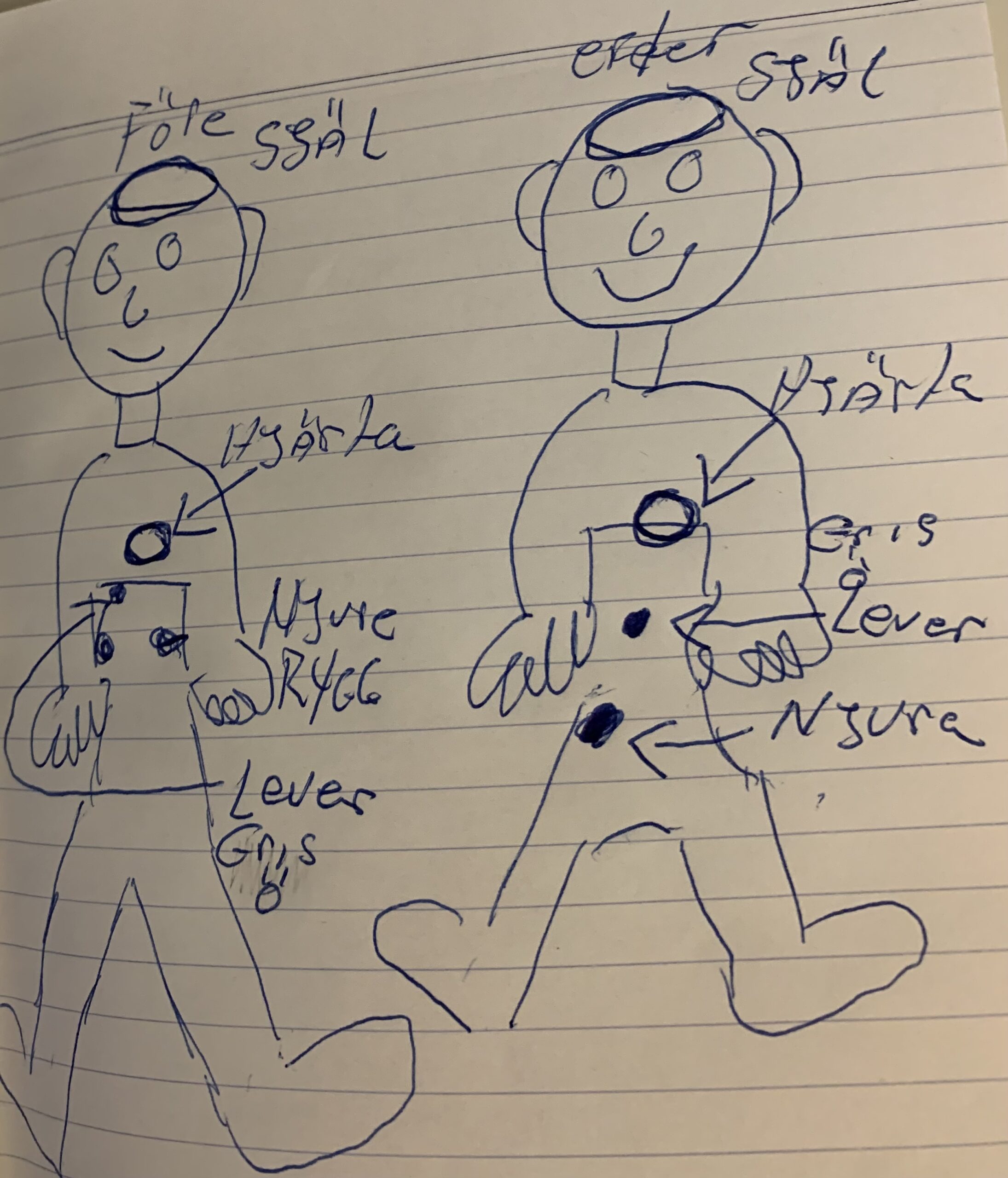

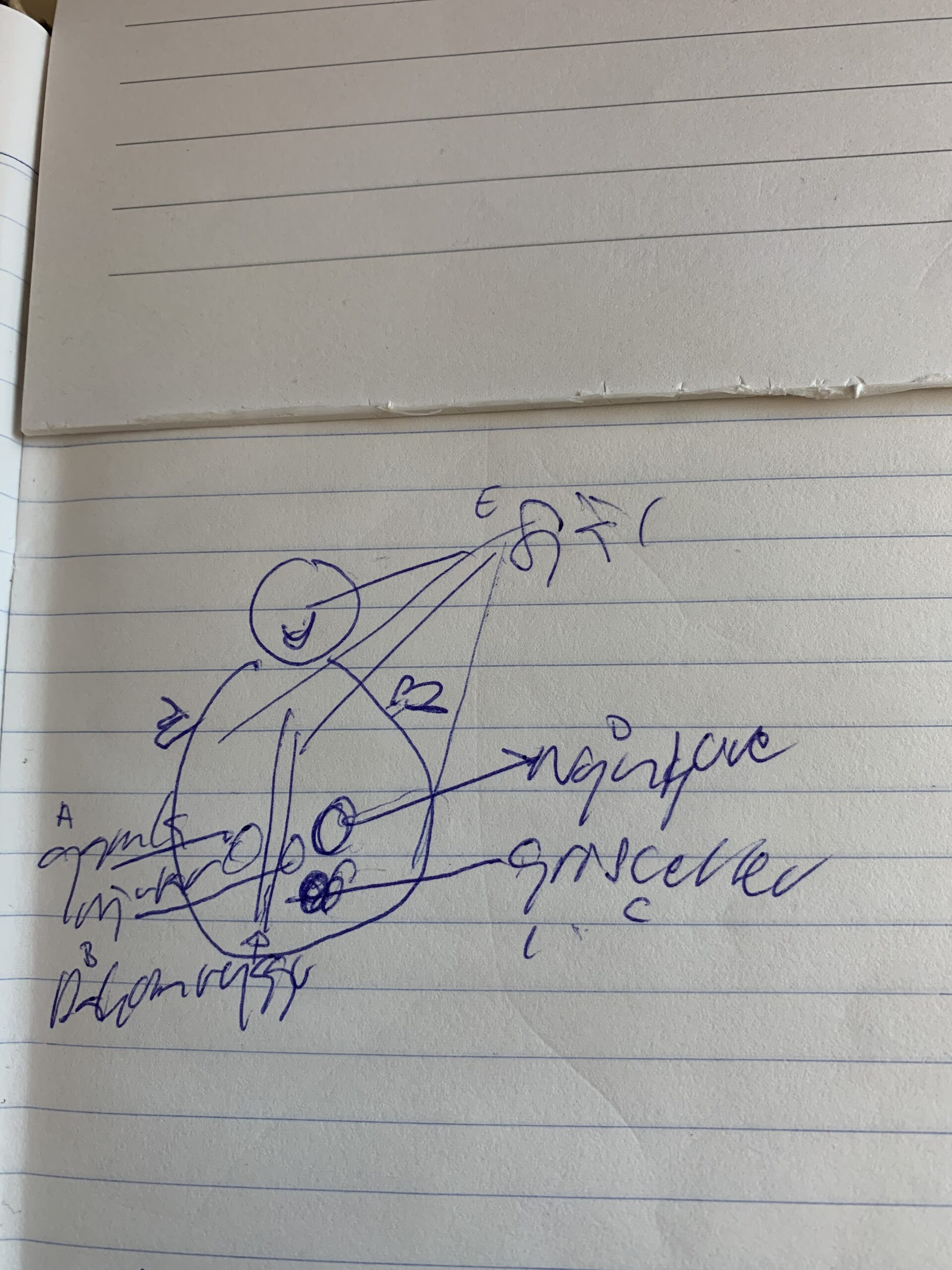

Ethnologists also ask people to describe their thoughts in ways that go beyond speech and writing. When I conducted interviews with nine diabetics in Sweden treated with insulin-producing cells from pigs, I asked them to make simple drawings of their bodies to indicate how they looked before and after the xenotransplantation.4 The drawings were a gateway to discussing their views of the human being within the context of biomedical developments. Three main views emerged: Some interviewees believed humans occupy a unique position in nature because reason, or the soul, is localized in the brain (Figure 1). Others believed humans, like animals, are cogs in the machinery of nature (Figure 2). Even though all the interviewees approved of xenotransplantation for survival, some wondered whether pigs would be humanized when given human DNA and whether this could lead to a change in the hierarchy of species. According to one participant, “It’s okay to have something animal in me, but it’s scary that the pig is being humanized.” Participants’ discussion and interpretation of their own drawings reveal the Swedish public’s complex views of xenotransplantation, which would be invisible without ethnology’s patchwork method.

Finally, as it aims to capture the relationship between objects, individuals and society, ethnology relies on the researcher’s field observations. Social anthropologist Arjun Appadurai believes field observations help illuminate the social life of things.5 Anita Hardon’s study of women in the Philippines illustrates this point well.6 She noticed that women in an economically disadvantaged neighborhood scraped together their last pennies to buy medicine for their sick children. Of course the medicines were intended to make the children feel better, but buying them also to showed the neighborhood that the women are responsible mothers. Hardon’s observations led to an ethnological insight—medicines can become social markers.

Interpreting Ethnological Research

Similar to medical and social anthropology, ethnology’s key findings come from a broad, comparative approach to cultural analysis. When I investigated views of reproductive medicine in 2012, my research led me to various folklife archives as well as to reproductive clinics. This research illustrates how ethnology’s “patchwork method,” including its comparisons with other times and environments, produces insights about research methods in the social sciences and ethnologists’ interpretations of their findings. One of my ethnographic observations involved meeting with a Middle Eastern couple consulting a doctor at the clinic. The aim of their visit was clear: if the examination showed the fetus was a girl, it would be aborted. They had five daughters and wanted a son who would eventually take over responsibility for the family. The doctor explained that abortions could only be carried out if the fetus showed serious pathological damage. My immediate reaction to the couple’s demand was disgust, but this feeling was trumped by their dismay (and suddenly my own) at the doctor’s reasoning. What kind of heartless society aborted children because of illness?

This moment illustrates culture-specific social systems operating in real time. The doctor framed his explanation within medicine as a normative system that values healthy individuals above all else; the couple frames their decision within a model of family succession that favours a specific gender order. Both my outrage over another country’s gender power structure and my obvious acceptance of the Swedish healthcare guidelines showed me that the observer’s, the researcher’s, eyes are clouded. This experience reminded me that all research involves subjective biases, or what the field of ethnology calls cultural science reflexivity.7

Ethnology also teaches us that knowledge production is not synonymous with clear-cut answers. In a medical humanities context, ethnologists are sometimes hired by authorities who want to know what the public thinks about problematic issues. What is “natural” in medicine? What should be prioritized in healthcare? Which medical technologies should governments invest in? Yet these stakeholders often express disappointment when ethnologists report that people are ambivalent and give neither a “yes” nor a “no,” but at best say “well, it’s complicated.” A woman with kidney disease who responded to a questionnaire on biomedicine simultaneously holds two different views on the subject: “I am completely against artificial fertilization and other interventions. It is unnatural. But a genetically modified kidney is okay, because without it I will die.”8 She juxtaposes her principled view on which biotechnologies should be authorized with a situational decision. Her comment also reveals an attempt to redefine what is natural and unnatural in medical care. Physical decay, i.e. death due to a defective organ, appears to be almost unnatural, whereas the technologically transformed body becomes natural.

Structural processes, such as medical treatments, have profound consequences for individuals. But behind all structures there are people—people who negotiate these frameworks. They may seek alternative methods for controlling the sex of a child, as recommended by nineteenth-century folklore, or push for laws that allow experimental treatments using animal organs. Ethnology teaches us that individuals are both carriers and builders of culture.9

Read Part I of this two-part series on Ethnology

References

[1] Susanne Lundin, “Ethnologi/Ethnology,” in Människan i centrum: nio röster om humaniora/The human being at the centre: Nine voices on the humanities, eds. Arne Jarrick, Görel Cavalli-Björkman and Kerstin Lidén (Votum, 2022) 83-94. I originally presented these ideas at The Royal Swedish Academy of Science (https://www.kva.se/en/) and then published them in the anthology cited here.

[2] Billy Ehn, Orvar Löfgren, and Richard Wilk, Exploring Everyday Life: Strategies for Ethnography and Cultural Analysis (Lantham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2016).

[3] Susanne Lundin and Markus Idvall, “Attitudes of Swedes to Marginal Donors and Xenotransplantation,” Journal of Medical Ethics 29 (2003): 186-192.

[4] Emily Martin, The Woman in the Body: A Cultural Analysis of Reproduction (Boston: Beacon Press, 1987). Martin used images in sensitive interviews and inspired my interview method in this study.

[5] Arjun Appadurai, ed., The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986).

[6] Susan Reynolds Whyte, Sjaak van der Geest, and Anita Hardon, Social Lives of Medicines (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002).

[7] James Clifford and George E. Marcus, eds., Writing Culture: The Poetics and Politics of Ethnography (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986).

[8] Quotes are from the 2004 survey Biomedicine och prioriteringar I vården/ Biomedicine and priorities in care, designed by Susanne Lundin and Andréa Wiszmeg and conducted by Lund University’s Folklife Archives team.

[9] Jonas Frykman and Orvar Löfgren, Culture Builders: A Historical Anthropology of Middle-Class Life, trans. Alan Crozier (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1987).