Blog by Susanne Lundin

In the Swedish parish of Anderslöv in the late 1880s, a pregnant farmer’s wife named Hulda placed an axe under the marital bed. She hoped her future child would be a boy because the farm needed a son to take over the business. A cracked clog in the same place would have signaled the family wanted to increase their chances of having a girl child. More than 100 years later, having a child and predicting the child’s sex are still expressions of human longing; however, today such desires are mediated by medical technologies such as ultrasound and artificial insemination. But what do a nineteenth-century axe and clog under the bed have to do with today’s biomedicines? Such questions attract ethnologists whose science is about why people do what they do, often unconsciously, and how different historical and social structures have influenced people’s activities. Yet the early ethnology, or rather the folklore research from which the subject emerges, had a different focus.

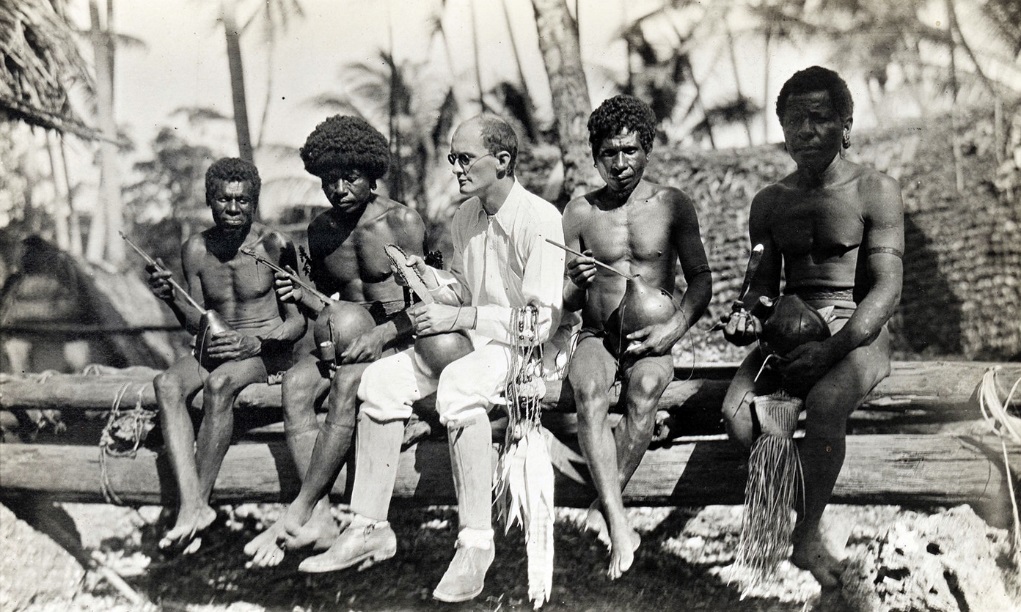

Like its sister science, social anthropology, ethnology is rooted in the ideological upheavals that characterized the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries with their efforts to capture the soul of the people. This lead to the folklore research of the early twentieth century, whose goal was to gain knowledge about people as social and cultural beings. But not just any cultural beings. Researchers directed their gaze towards the others, which meant peasants, the working class, and the so-called primitive cultures in distant countries. The we looking at these others belonged to the upper classes, the bourgeoisie, and the scientific community. Two basic perspectives were distinctive at this time. The first described social and cultural contexts from an outside perspective (Figure 1); the second captured the essence of culture through participation and therefore applied an insider’s perspective (Figure 2). Researchers aimed to save cultures feared to disappear—be it the everyday life of a Swedish farming community or populations in countries far away from their own. Their knowledge goals were incorporated into the emerging museum business, where they still exist today. However, scientific research in general has undergone major changes, and these changes are clearly reflected in today’s ethnological research.

This is part one of a two-part series on the role of ethnology as a humanistic discipline, particularly its contribution to understanding the cultural impact of current medical practices and research. Ethnology describes itself as a science that takes the pulse of society. How this is carried out and what questions ethnology asks is the overarching theme throughout the two parts of the series. In this first part, I present some of the methodological and analytical tools used by ethnologists.

A Keyhole into Culture

A common thread running from early folklore research to contemporary ethnology concerns people’s ideas, actions and objects for organizing life. Folklorists strove for objective descriptions of social groups, but today’s researchers perform critical and cultural analyses of social phenomena. The 1979 publication of the now classic Den kultiverade människan (The Cultivated Man) by Jonas Frykman and Orvar Löfgren became a watershed moment in Swedish ethnology that laid the foundation for future ethnologists’ studies of class, culture and gender.1 The authors were influenced by the social anthropologist Mary Douglas’s discourse analyses of how taboos around cleanliness in different cultures create social categories.2 Yet whereas Douglas examined classification systems in other cultures, Frykman and Löfgren turned their attention to how norms about cleanliness served to maintain social differences in late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Swedish society. An illustrative example is how the working class was associated with uncleanliness, which was, in turn, associated with immorality and criminality; the bourgeoisie, on the other hand, was associated with cleanliness and high morals, giving them a natural right to social privileges. Similar models of thinking have led not only to new positions of social power but also to an unequal balance of power between the genders. Cultural anthropologist Emily Martin’s extensive studies of gender and class show that menstruation was seen as “unclean” and therefore became a tool for separating women from the “pure” patriarchal social body.3

For ethnologists, everyday life becomes a keyhole into how cultural norms are activated in people’s lives, allowing us to see what is considered normal and thus obvious and invisible. Ethnology’s insights reveal the unspoken rules that determine daily routines in homes or workplaces; or, in a medical humanities context, how the digital delivery of medical care creates particular behavioural patterns. For instance, today’s patients have become more like customers.4 Ethnology examines how such phenomena are rooted in complex historical and cultural patterns.

Ethnology encompasses research areas as varied as human social life—cultural heritage, the digitalization of everyday life, medicine, consumption patterns, violence and ethnicity. A key theme that has emerged in contemporary ethnology is the body, which includes health and the culture surrounding health and the body. Ethnology, like social anthropology, examines the role of biotechnological developments in social change. Margaret Lock and Vinh-Kim Nguyen ask what it means when technologies such as in vitro fertilization and xenotransplantation enable the creation of life outside the body.5 Treatments that were previously not possible, or even conceivable, are giving rise to a growing demand for cells, tissues, organs and certain medical tests. Both society and individuals must manage the consequences of such demand. Additionally, medical advances challenge established norms and therefore lead to a reassessment of ethical and cultural guidelines.

One way for ethnologists to understand such complex social processes is to examine the relationships between time, space and society. This means that ethnologists exploring the present often turn to archival material. Swedish folklife archives are filled with material on the rural populations and the working-class of the industrial era, such as the folklife archives of the Scania Music Collections in Lund and Nordiska Museum in Stockholm. They cover everything from annual festivals to medicine to views on work, the family, and childbirth (including the description of the peasant mother Hulda placing an axe under her bed to influence the sex of her future child). These records provide insight into social structures and tell us about the hopes that permeated people’s lives. They also provide insight into a series of actions that went against the Church’s guiding principle of accepting the course of fate. For example, records contemporaneous with Hulda’s personal account warn rural communities that such actions had consequences: the Church’s condemnation as well as the future child being ostracized and forced to live as a werewolf. Like yesterday’s superstitions, today’s techniques for “changing the course of fate” are not simply characterized by the hope of treatment results. As the ethnologist Stefan Beck and many other cultural researchers discuss, our medical advancements reflect both the joy of medical progress on the one hand, and the fear of “messing with nature” on the other.6

As we have seen, ethnology can be characterized by its object—the complexities of human cultures and how individuals are situated within them—and by its practitioners, the researchers who extrapolate structural insights from cultural phenomena. The second part of this two-part series will focus more on the practitioners, especially the importance of reflexivity as an analytical and critical tool in the discipline.

Read Part II of this two-part series on Ethnology

References

[1] Jonas Frykman and Orvar Löfgren, Den kultiverade människan (Malmö: Gleerups Utbildning AB, 1979).

[2] Mary Douglas, Purity and Danger: An Analysis of Concepts of Pollution and Taboo (London: Routledge and Keegan Paul, 1966).

[3] Emily Martin, The Woman in the Body: A Cultural Analysis of Reproduction (Boston: Beacon Press, 1987).

[4] Ingrid Fioretos, Kristofer Hansson, and Gabriella Nilsson, Vårdmöten: Kulturanalytiska perspektiv på möten inom vården (Lund: Studentlitteratur, 2013).

[5] Margaret M. Lock and and Vinh-Kim Nguyen, An Anthropology of Biomedicine (Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010).

[6] Stefan Beck, “Translating Experience into Biomedical Assemblages. Observations on European Forms of (Imagined) Participatory Agency in Healthcare,” in Health Promotion and Prevention Programmes in Practice, eds. Thomas Mathar and Yvonne J.F.M. Jansen (Bielefeld: transcript Verlag, 2010) 195-222; Susanne Lundin, “Moral Accounting. Ethics and Praxis in Biomedical Research,” in The Atomised Body: The Cultural Life of Stem Cells, Genes and Neurons, eds. Max Liljefors, Susanne Lundin and Andréa Wiszmeg (Lund: Nordic Academic Press, 2012).