Film Review by Robert Abrams

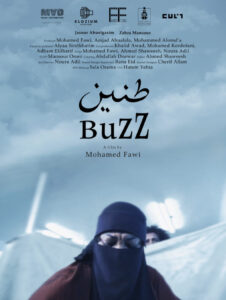

Buzz (short film, Sudan 2022, directed by Mohamed Fawi, produced by Amjad Abu Alala, distributed by Mad Solutions), world Premiere at the 2022 Cairo International Film Festival (CIFF)

Buzz, a new short film created by the visionary director Mohamed Fawi, presents, in just under 20 minutes, several different themes that flow together naturally, without competing separately for the viewer’s attention. First, the film highlights the isolation and culturally sanctioned burdens of women in the Middle East and their imperative to assist each other. There is an old Auntie at the beginning of this story who generously aids her overwhelmed young niece, Zahra (Zahra Mansour) a woman caring for a newborn, two other children and a dying mother, all apparently on her own. The aunt offers to care for the baby and young children while their critically ill grandmother is taken by Zahra to the hospital.

That’s not all. The dying older woman also has a twenty-something son, Jasour (Jasour Abuelgasim). Jasour is scolded on his arrival at the family’s home by his sister for his absence over the previous 2 months as their mother’s condition worsened, and also shamed for his unkempt grown-out hair. Jasour is mostly silent but affectionate with his mother. There is also an early hint of the malady that could explain his absence and withdrawn personality —a slight but distinct buzzing sound heard just before his arrival and a then a head-shaking motion as he kneels to greet his bed-bound mother.

It appears that Jasour has a tic disorder, and with it, the onus of stigma that it carries and its limiting effect on his life. This condition is poorly understood by his sister, Zahra, and by extension, the whole of society. Often enough, the behavior of someone like Jasour is misread as being purposeless or disconnected from emotion but still under the individual’s control. Neither is true. In this case, the anticipation of seeing his mother so ill appears to have stimulated Jasour’s customary tic, but this expression is nevertheless involuntary. Meanwhile, Jasour the person is seen to be intelligent and loving as he places his ailing mother on a stretcher and gently guides her into an ambulance. He has evidently done this before and knows exactly what to do now.

Jasour is far too organized and emotionally present to be psychotic, though auditory hallucinations—in this case hearing a buzzing insect that isn’t there– are not normally features seen in Tourette’s disorder and related conditions. Low-dose atypical antipsychotics are, however, the pharmacological agents most frequently used in standard treatment. But the buzzing sound would alone be justified by the director’s artistic license, as a way of emphasizing the distress and lack of control experienced by Jasour. The buzzing sound is also consistent with the variations in neurobiology and presentation of tic disorders, entities that are informally grouped under the rubric “Atypical Tic Disorders.”1 After all, not every tic disorder involves the socially inappropriate vocalizations characteristic of Tourette’s.

The film is also about a cruel medical system, featuring the heartless indifference of an ambulance driver as the aged mother rides with her adult children to the hospital. Once at the facility, Jasour and Zahra are confronted with an à-la-carte-pay-in-cash requirement for every imaginable aspect of their mother’s care. Inevitably they run out of money for critical medications. The young hospital physician seems to know his patient from previous admissions, so there is at least some continuity of care; and he appears competent, a bit abrupt, but not unkind. He is well aware of the importance of timely intervention. But of course, this doctor is obliged to contend with the same deplorable system as his patients.

Buzz can be seen as social commentary on at least three fronts: the unbalanced level of burden that devolves upon women; the lack of understanding and compassion accorded to those who suffer from tic disorders; and a system of medical care that is efficient but soulless. These three themes coalesce in the final scene, in which the mother is expected to die from the most recent in a series of myocardial infarctions. If so, she will die without the comforting presence of her son and daughter, because the hospital rules do not permit family visitation in the ICU.

The meaning of such an isolated death comprises a fourth, perhaps the most critical, theme in the film, not only from the family’s point of view, but also from that of the patient herself. In fact, Mr. Fawi always positions the camera in Buzz to reflect the dying woman’s point of view (POV), so in that sense the entire film is told through her eyes, even if she is speechless. At one point she tries to pull out her IV port, a sign that usually suggests delirium, a state of confusion often seen in dying patients. But here this act could be also be interpreted as a metaphor for the mother’s rejection of a futile last hospitalization; and it could also indicate her wish to die at home, surrounded by her family, rather than taking her last breaths in an emotionally arid ICU, where she will feel abandoned by and disconnected from those she loves.

The film’s final scene is thus a deathwatch minus the patient. Brother and sister wait glumly outside of the ICU, the daughter for once silent; and Jasour afflicted now with a crescendo of buzzing sounds that, in the context of acute anxiety and anticipatory grief, are much louder and more irritating to him than before, calling forth jerky, determined gestures to shake a non-existent insect away from his head. It is on that striking, memorable note that, after a brief twenty minutes, this extraordinary film abruptly ends. In that small detail, although in minutes instead of years, this film is a worthy reprise to You Will Die at Twenty,2 a 2019 film directed by the producer of Buzz, Amjad Abu Alala.

References

[1] Narrapareddy, A. et al. Altered interoceptive sensibility in adults with Chronic Tic Disorder. Front. Psychiatry 21 June 2022. Vol.13. https://doi.org/10.3389/psyt 2022 914897

[2] Abrams, R. Counting the days, not living them: You Will Die at Twenty, by Amjad Abu Alala day (film reviews). Journal of Medical Humanities (2021) 42:503–504 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10912-021-09703-4