Blog by Dr Emilie Taylor-Pirie

In the sweltering heat of British India, a doctor was working late one evening in his laboratory. His scalpel glinted with the sweat from his brow as he dissected his 1000th mosquito, gently separating the flesh of the thorax from the abdomen. He was tired, a little feverish, and about to give up and go to bed when he saw them. Tiny speckled dots—plasmodium parasites—peppering the cells beneath the lens of his microscope. This was his eureka moment.

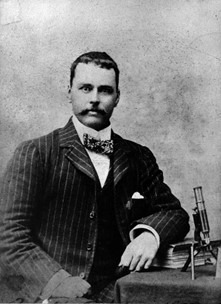

December 2022 marks 120 years since Britain won its very first Nobel Prize. It was given to Scottish pathologist Ronald Ross for proving that mosquitoes transmit malaria.

Ross had made a groundbreaking discovery—today vector control (targeting the mosquitoes that transmit the malaria parasite) is still the cornerstone of the World Health Organisation’s anti-malaria strategy.

As a member of the Indian Medical Service and later professor at the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, Ross gained fame as an authority on science. He published widely on malaria prevention, invented a diagnostic microscope, and led several expeditions to West Africa funded by the Royal Society. He gave one of the earliest BBC radio lectures—broadcast to over a million—in March 1924, a month before George V would become the first British monarch to speak on the radio.

And yet, few people outside medicine have heard of Ronald Ross, despite his potential as a pub quiz answer. Who was the first British Nobel laureate? (I first heard about Ross during my biology degree—a cell in the gut of the mosquito is named after him: the Ross cell).

Those who have heard of him likely know him through a poem he wrote moments after his discovery:

This day relenting God

Hath placed within my hand

A wonderous thing; and God

Be praised. At his command,

Seeking His secret deeds

With tears and toiling breath,

I find thy cunning seeds,

O million-murdering Death.

I know this little thing

A myriad men will save.

O Death, where is thy sting?

Thy victory, O Grave?[1]

Ross’s poem is dutifully trotted out on World Mosquito Day (20th August), which is celebrated annually on the very day that Ross saw those speckled dots. But the fact that he wrote poetry is not simply a fun piece of trivia to be filed away with the knowledge that Romantic poet John Keats was trained in medicine or that we share 60 percent of our genes with bananas.

Rather, Ross’s poetry is an integral part of the history of malaria. In 1910 Ross had published an anthology of poetry in tandem with a textbook on malaria perceiving the two works as complementary threads to the story of his discovery. It included that famous stanza, which was reprinted in the British Medical Journal and The Lancet, in national and regional newspapers, in articles, in op-eds, and in biographies. Additionally, it appeared in posthumous radio plays, adorned the menus at anniversary luncheons, and was even chiselled into stone—on a monument erected to Ross in Calcutta in 1927.

Viewed as a lyrical rendition of his “eureka moment,” the poem took the British imagination by storm, earning Ross a reputation as “the poet who conquered malaria.” For many it provided an access point for the public understanding of science. The poem laid bare the emotional stakes of medical research, providing a humanising narrative to counter the imagined objectivity of experimental science.

Whilst working as a doctor in the Indian Medical Service, Ross frequently turned to poetry to express the frustrations he felt at the limits of scientific medicine:

In this, O Nature, yield I pray to me,

I pace and pace, and think and think, and take

The fever’d hands, and note down all I see,

That some dim distant light may haply break.

The painful faces ask, can we not cure?

We answer, No, not yet; we seek the laws.

O God, reveal thro’ all this thing obscure

The unseen, small, but million-murdering cause.

Following his discovery, Ross received letters from would-be patients wanting diagnoses, doctors wanting advice, even fans wanting autographs. Many correspondents used poetry as a kind of shorthand, quoting his verses or penning their own to convey their affection, to lay bare their admiration, to communicate in-jokes, or to offer commentary on the medical profession.

Thus, poetry was not just a strategy for communicating science to the public, or a means of processing emotion, but a language in which to express the social and political aspects of malaria prevention.

Ross himself believed that poetry and science were kindred practices; he even gave a lecture on the subject at the Royal Institution in 1920. For him, the perseverance and problem solving of the scientific imagination was embodied in the meticulous design of poetic form.

Fellow parasitologist Ronald Campbell Macfie insisted that “it was the great poet in him that made him a great man of science […]. The same fine faithful technique that found the microbe in the mosquito finds the precise immortal word. The same surgent imagination that inspired his poetry surges in his science.”[2]

Ross was born a Victorian in a period famous for its polymaths, but he lived and worked through the very different professional culture of the twentieth century. Towards the end of Ross’s life, his friend and biographer Rodolphe Louis Mégroz claimed that whilst Ross had gained “undying fame as a medical scientist,” he had “begun as a poet, and remained essentially a poet.”[3] It was a claim with significant narrative appeal, implying a crossover skill set that was—by the 1930s—thought of as rare and special.

A medical humanities approach to the history of malaria spotlights the cultural contexts that mediate the relationship between science and society, helping us to reflect on our own disciplinary landscape with its unwritten—and sometimes written—assumptions about the arts and sciences. Government funding initiatives pit STEM against the arts and humanities, revealing a higher education system that siloes the so-called “creative” subjects from the more “objective” ones. There is a tacit assumption that people are “naturally” suited to one “type” of subject.

But change is afoot. Across the country we see the emergence of centres for cross-disciplinary collaboration, grant funding for interdisciplinary research, and degree programmes focusing on problem-based learning by scaffolding knowledge from multiple subjects. These innovations challenge the false dichotomy of Science and Art (there are many sciences and many arts), recognising that STEM students can—and should—employ critical and reflective tools from the arts and humanities and that the latter subjects can use scientific methodologies to enrich their own practices.

The recent anniversary of Britain’s very first Nobel Prize should remind us that medicine and the humanities have long been productive bedfellows, helping us to understand the dynamic entanglements between science and culture.

References

[1] Ronald Ross, “Reply” in Philosophies (London: John Murray, 1910).

[2] Ronald Campbell Macfie, “Poems by Sir Ronald Ross,” The Bookman (September 1928): 315.

[3] R. L. Mégroz, “Ronald Ross as Fiction Writer,” The Bookman (October 1930): 15.

Dr Emilie Taylor-Pirie is a Leverhulme Trust Research Fellow at the University of Birmingham. She holds a BSc in Biology and higher degrees in the humanities. Her research interests encompass the history of medicine and medical humanities and include tropical medicine, gut health, and the public understanding of science.