Book Review by Professor Robert Abrams, Weill-Cornell Medicine, New York

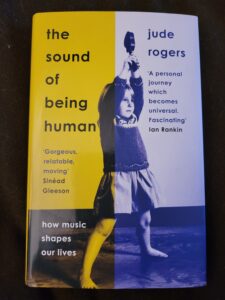

The Sound of Being Human by Jude Rogers, published by White Rabbit, London, UK, 2022

In recent years a fascinating neurobiological literature has emerged, describing the connections between music and one’s earliest memories and emotions.[1] Clinical applications have also been developed: Patients with advanced dementia who are speechless can still sing long-remembered tunes if given cues; and listening to much-loved music appears to enhance mood states in patients with severe cognitive impairment.[2],[3]

In recent years a fascinating neurobiological literature has emerged, describing the connections between music and one’s earliest memories and emotions.[1] Clinical applications have also been developed: Patients with advanced dementia who are speechless can still sing long-remembered tunes if given cues; and listening to much-loved music appears to enhance mood states in patients with severe cognitive impairment.[2],[3]

These basic and clinical advances are summarized in Jude Rogers’s new book, The Sound of Being Human, but as a journalist and respected critic of popular music, her professional expertise is in the history and personalities of the musical scene of the 1980s and 1990s. Nevertheless, as the title suggests, it is describing the human experience of listening and emoting to the sound of music that is her special gift; and the book is moving and powerful when she stays in this lane and does not lose her thread either in neuroscience or intricate insider discussions of popular-music artists.

The Sound of Being Human is loosely structured around the author’s personal history, revealing the memories associated with popular songs of her childhood, youth and young adulthood. Her first selections are closely linked to the death of her father when she was five years old. On the eve of his departure to the hospital for a surgical procedure, her father had asked the young Jude to inform him, when he came home, which song had reached “Number One” on the pop charts during his absence. He never returned to learn the answer.

That “Number One” song was apparently Pipes of Peace by Paul McCartney. But it had been another hit, a previous “Number One,” that had been the real favorite of her father’s. That song, Only You, by the pop duo Yazoo, or in an acapella version by another group, evoked the most enduring emotional memories for the author. Either rendition prompted the same heightened response. For example, hearing this music played aloud at a shopping center would be enough to interrupt the adult Rogers’s pressing errands and bring her to a state of imagined conversation with her father, during which she might tell him all about the person she had become, the teenager and then the grown daughter, wife, mother and award-winning journalist he never knew. In this writer’s psychiatric practice with older patients, such “conversations” with those who have been loved and lost can be among the most cathartic features of mourning.

Another song that prompted memories of Rogers’s father was ABBA’s Super Trouper. In this music, Rogers writes that she found “something in the movement in the song that feels full of sweet, genuine, unquenchable life.” (One might perceive a wishful reference to her dead father in the phrase “unquenchable life”). Not only did this music bring her back to a cherished time and place, but it is also the song she describes joyfully playing to her own toddler son, in that single act creating a bridge from past to present to future. In other examples as well, links to her youthful watershed moments enable Rogers to find beauty and meaning in music that others might see as merely catchy tunes or “auditory cheesecake.”

Although the author’s emotional connections with music are relevant and coherent, the problem with this book is that most of it is given over to a highly detailed history of pop culture starting in the 1980s. to which not all readers will relate. It is when her comments on music are anchored to her own emotional and social development, mainly at the beginning and the end, that the book has broader appeal.

At its best The Sound of Being Human describes, in a lucid and original style, what music does to us and for us: Songs are triggers to pleasure and sadness (or the uniquely human combination of pleasure and sadness). Rogers describes such phenomena in this way: “A song laces the specifics of this picture together, carries its elements along.” Fittingly, then, Rogers’s prose is highly expressive, and in an alliterative and staccato way, musical itself: When one responds to a song, she writes, a person feels “stimulated, soothed, alert, afloat.”

For Jude Rogers it is popular music that moves her, but it could as well be any genre or era of music. If our responses to music reveal a capacity to love, mourn and live life again in retrospect, then creating and enjoying music must surely be among the distinctive features that make us human. That, although often obscured in the minutiae of rock-music legend, is the book’s central thesis.

What the author has created here should also be understood as a memorial to the father she lost at a developmentally vulnerable age. The book’s dedication makes this point unmistakably: “For my Dad, and for little me.” In the end, the parts of The Sound of Being Human that I loved were those dealing with the author’s intimate musical memoirs and their importance for successful mourning, for dealing with an unbearable early loss. But these sections comprise a comparatively small portion of the book’s “real estate.” In the rest, basically a showcase for Rogers’s encyclopedic knowledge of popular music, I felt lost. Perhaps she was attempting to posthumously impress her music-loving father with the depth of the expertise she had acquired; or else The Sound of Being Human is simply an example of an author starting to write one book but actually writing two.

References

[1] Trimble M, Hesdorffer D. Music and the brain: the neuroscience of music and music appreciation. Br J Psych Int. 2017;14(2):28-31. doi:10.1192/s2056474000001720.

[2] Baird A, Samson S. Music and dementia. Prg Brain Res 2015; 217:207-35. PMID:25725917. doi:10:1016/bs.pbr.2014.11.028.

[3] Baird A, Thompson WF. When music compensates language: a case study of severe aphasia in dementia and the use of music by a spousal caregiver. Aphasiology 2018; 33(4): 1-7. Doi:10.1080/02687038.2018.1471657.