Podcast with Riva Lehrer

Riva Lehrer is an artist, writer, and curator who focuses on the socially challenged body. Best known for representations of people whose physical embodiment, sexuality, or gender identity have long been stigmatized. Lehrer’s memoir, Golem Girl (One World/ Penguin Random House), won the 2020 Barbellion Prize for Literature and was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award.

Riva Lehrer is an artist, writer, and curator who focuses on the socially challenged body. Best known for representations of people whose physical embodiment, sexuality, or gender identity have long been stigmatized. Lehrer’s memoir, Golem Girl (One World/ Penguin Random House), won the 2020 Barbellion Prize for Literature and was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award.

She is represented by Regal Hoffman & Associates, NYC, and by Zolla/Lieberman Gallery, Chicago.

Read Dr. Isabella Watts’ review of Golem Girl on the Medical Humanities blog.

Listen to the podcast below:

TRANSCRIPT

BRANDY SCHILLACE: Hello and welcome back to the Medical Humanities Podcast. I’m Brandy Schillace, Editor in Chief of the Medical Humanities Journal for BMJ. Today, I’m really excited to have with me Riva Lehrer, who’s going to be talking to us about her memoir. It’s a book called Golem Girl, and it has so much to offer and so much to say about the disability community, but also just being human and being seen as a valuable and worthwhile human being. And so, Riva, thank you so much for joining us.

BRANDY SCHILLACE: Hello and welcome back to the Medical Humanities Podcast. I’m Brandy Schillace, Editor in Chief of the Medical Humanities Journal for BMJ. Today, I’m really excited to have with me Riva Lehrer, who’s going to be talking to us about her memoir. It’s a book called Golem Girl, and it has so much to offer and so much to say about the disability community, but also just being human and being seen as a valuable and worthwhile human being. And so, Riva, thank you so much for joining us.

RIVA LEHRER: I’m absolutely thrilled. I’ve become a fan of the podcast, so thank you for having me.

SCHILLACE: Absolutely. So, this book has been really fascinating, and I think the book itself has had an interesting journey, even as you have had an interesting journey.

LEHRER: [chuckles]

SCHILLACE: And of course, coming out in the middle of a pandemic, it’s both unfortunate in some ways, right? Because launching a book in a pandemic is hard, but also, really indicative of so many things that you talk about and the hurdles and obstacles. And so, I was wondering, first of all, tell us a little bit about yourself and about this book journey.

LEHRER: Well, definitely, it’s been an irony sandwich having a book come out about impairment. Yeah, so, bringing out a book about impairment and human fragility in the middle of a pandemic is not something I would recommend for the faint of heart.

SCHILLACE: Yes!

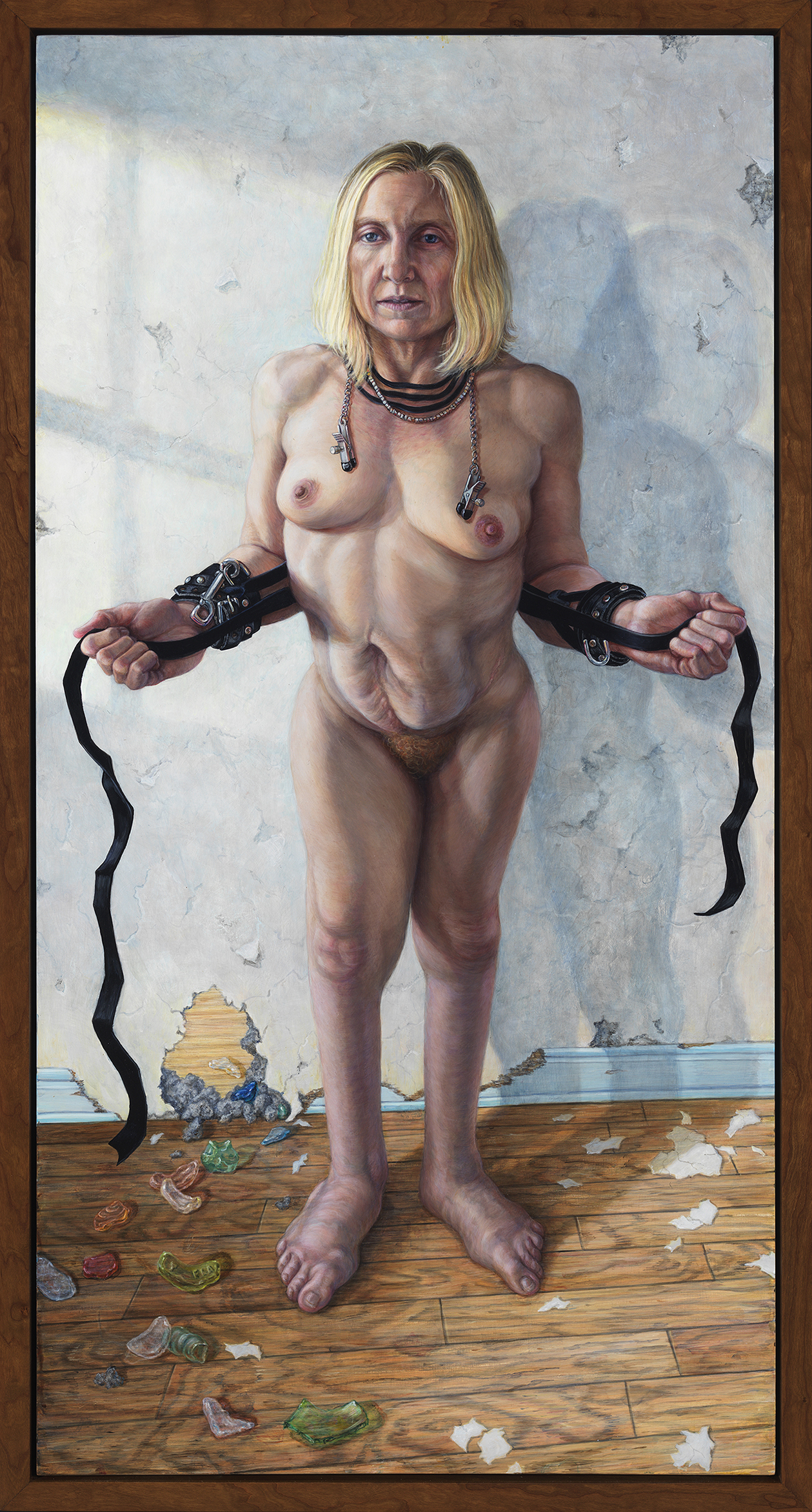

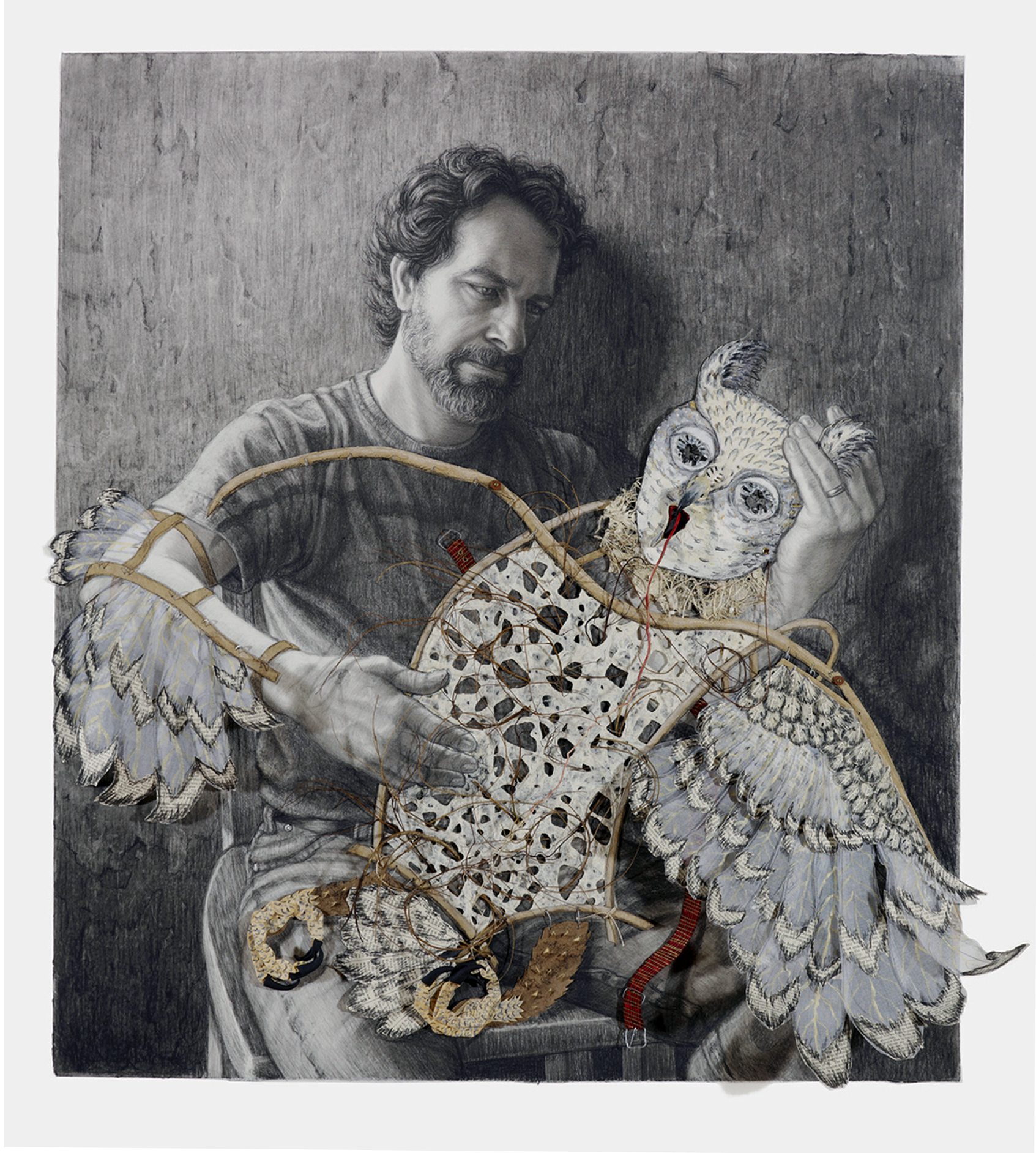

LEHRER: The book took me about eight years to write. Originally, it was just going to be a document for my family to describe my studio practice because what I really am, usually am, is an artist. I call myself a portraitist, but really, what I am is an artist who’s trying to understand embodiment through the use of portraiture. I don’t see myself as a traditional portrait painter at all. So, the way I got there is complex and completely tied in with my life as a disabled person. And as I went on and started trying to describe the book, I mean, I’m sorry, describe my work for my family, I ended up, as I do in public talks, having to describe how I became who I was and went to do what I do, which is to do portraits of people who deal with stigma, which is what I really focus on. So, I’m trying to describe this for my family, so they’ll have something when I’m no longer around. And I started to do research into my family to understand some things that I’d never really thought about, went home, interviewed some family members thinking I was just gonna fill in some details. And they started telling me stories that had me absolutely on the floor, prone, you know, prone, looking up at the ceiling in astonishment. And then all of a sudden, it started to be a memoir.

SCHILLACE: Yeah.

LEHRER: So, I did that, and my publisher my publisher is One World, a division of Penguin, and they focus on social justice. And they were so excited because I was the first person that I know of who was working on disability. They’re mostly known for authors who are people of color dealing with race and national origin, things like that. So, they thought the book was just gonna do great guns and had a book tour planned. I was excited out of my mind. And then COVID.

You know the beginning—I’m gonna date myself—the beginning of Monty Python. There’s a giant cartoon foot that comes down.

You know the beginning—I’m gonna date myself—the beginning of Monty Python. There’s a giant cartoon foot that comes down.

SCHILLACE: [laughs]

LEHRER: It goes stomp, stomp, stomp!

SCHILLACE: Yeah, yeah.

LEHRER: I, yeah, I still have the imprint of the boot on my head.

BOTH: [chuckle]

LEHRER: So, that’s what happened to the book, and it’s been really hard. It’s been hard.

SCHILLACE: Yeah, I completely understand, I mean, to a lesser degree. I launched mine in 2021 and similarly—

LEHRER: Oh!

SCHILLACE: Yes, so I feel. I feel you.

LEHRER: I’m so sorry!

SCHILLACE: I do. I know! It’s frustrating. It’s actually one of the reasons why I have been doing so much with authors in this podcast for Medical Humanities. And if you’re a regular listener, you’ll know that we’ve had several authors on, and we’re going to be doing that more. Because these books that really grapple with art, with queer identity, with bodies, with disability, with coming to terms, with the self and the embodiment of just being alive are incredibly powerful, important social justice medical humanities books. And they are, they’re threatened to be lost underneath all of the sort of landside of everything else that’s going on. And so, that’s one reason why I wanted you on here today, because this is a critical time for a book evaluating these things. Because now, we’re all living in a world where we’ve had to drastically reevaluate our bodies in space.

LEHRER: Well, it’s been…oh, gosh, fascinating and horrifying, because I truly thought when the pandemic hit, I thought, OK. There had been this efflorescence of disability culture right beforehand. I mean, literally like, weeks beforehand, all of these amazing things had happened. A lot of things had come out in the New York Times. A lot of things had come out in the New York Times that were documenting art and film and performance, and just there’d been an enormous grant that came through the Ford Foundation that I’d been one of the recipients. It really looked like the doors were finally opening.

SCHILLACE: Mmhmm.

LEHRER: So, the pandemic hits, and I think, all right, well, at least we’re in place because they’re gonna need us. Like, we are the people who know how to handle physical catastrophe, illness, strategizing how to do things when the old ways are just gone. Like, OK, we’re ready. And instead, what I saw was this huge backlash!

SCHILLACE: Mmhmm.

LEHRER: So, first, you know, in the early days of the pandemic, and I’m sure Alice Wong spoke to this, they immediately told us—I mean, there was no pussyfooting—you’re not important.

SCHILLACE: I understand.

LEHRER: —you know, the ladder, low on the ladder for getting treatment or a vaccine if and when it comes. And also, you might not be able to even see your doctor. You may not be able to get your normal medical equipment. Gee, sorry! But we gotta take care of the healthy 30-year-olds and make sure they’re not gonna get hurt.

SCHILLACE: Right.

LEHRER: So, we’re all sitting there just horrified. And for instance, I’m one of the people who fought incredibly hard here in Chicago when the vaccine started to be rolled out. Disabled people were nowhere, nowhere on the roster, just not at all.

SCHILLACE: Mmhmm.

LEHRER: And I started to call. I mean, I’ve been here a long time, and some people know me. And I just went ballistic, and I was part of the team that got the city to change the protocol. But it’s been…it’s been heartbreaking also, I think, because everyone is so terrified.

SCHILLACE: Mmhmm.

LEHRER: The last thing they wanna look at is what it means to be disabled. And I’ve noticed that articles about long COVID, they kind of come and go. Like, they’ll start to talk about it. Then they’ll go away for a really long time because nobody really wants to face the fact that all of a sudden, we’re gonna have hundreds of thousands of new disabled people, and we don’t know their trajectory at all.

LEHRER: The last thing they wanna look at is what it means to be disabled. And I’ve noticed that articles about long COVID, they kind of come and go. Like, they’ll start to talk about it. Then they’ll go away for a really long time because nobody really wants to face the fact that all of a sudden, we’re gonna have hundreds of thousands of new disabled people, and we don’t know their trajectory at all.

SCHILLACE: No, no. And there’s no…. And it’s interesting because I actually have been following that myself, and I feel as though the very nature of hesitance around taking articles or writing articles or reading articles about long COVID is part of a, it’s also, well, sorry. I don’t mean to be disarticulate here, but it’s also part of our inability to face mortality too.

LEHRER: Oh, exactly.

SCHILLACE: Because you don’t see articles talking about the death tolls. You don’t see, people don’t know about the death tolls. I actually had someone say to me, “Well, at least they’re lower now.” And I was like, “Have you been watching?”

LEHRER: [laughs] Lower than what?!

SCHILLACE: Because they haven’t, ‘cause the articles, you know, the articles that were hitting very hard, they’re not there now. And why not? Well, some of it is our human resil-, some of it is resilience-based, right? At some point you just can’t live under that anymore, and you can’t focus on it. But another is just we’re terrified of long-term consequences where we live in a society of disposability. You throw something, and you get a new one, right?

LEHRER: Right.

SCHILLACE: We should be able to do those to bodies too, right? You should just be able to go to the doctor and medicine fixes you, and now it’s right back to normal. But it’s not back to normal. And I was trying to explain to someone that death and dying, losing someone is a lot more like an amputation. Like, you never, there is no normal that you go back to. And long COVID is turning out to be the same kind of thing. It’s not a well, after this extended period of time, I will be back to normal. Normal isn’t there.

LEHRER: Well, you know—

SCHILLACE: Doesn’t mean anything, anyway. It’s a weird word.

LEHRER: You know, the language of medicine is always, the prefix re- is always in there.

SCHILLACE: Yeah.

LEHRER: Rehabilitation, you know, repair, renewal, restoration. I mean, there’s so many. And it’s this embedded fantasy that has always been there, that we have a permanent normal body and that healing is about regaining that permanent body.

SCHILLACE: Mmhmm.

LEHRER: And it’s never been true.

SCHILLACE: Right.

LEHRER: And you know, I try and point out to people that we are always changing, that we have this strange idea that like, there’s childhood change, there’s puberty, adolescence change, there’s a period between ah, 24 to 50 where we don’t change. Huh?

SCHILLACE: [chuckling] Yeah.

LEHRER: And then all of a sudden, 50 and, you know, this thing called middle age, where all of a sudden, we’re noticing that we changed. And then the dread, the dread country of being old.

SCHILLACE: Yeah.

LEHRER: And it’s like we have these gears in the car, and we just think that we’re gonna be in one gear for a really long time until we’re forced to go to the other gear, and that there’s been no traveling.

SCHILLACE: Right!

LEHRER: You know? Like, we’ve just been sitting in this car in this one gear, and we didn’t go anywhere. [laughs]

SCHILLACE: Right, right.

LEHRER: And you know, I, you know, I’m a portraitist.

SCHILLACE: Mmhmm.

LEHRER: And sometimes when I’m working with somebody, there will be weeks or months between sittings, and they’ll come back. And I can see all the changes in just like mm, a couple months, you know.

SCHILLACE: Right.

LEHRER: I’ve painted people who were pregnant who started working with me when they were three months pregnant and ended two weeks before birth, and I nearly threw myself off a roof, right?

BOTH: [laugh]

LEHRER: I’m like, OK, what do I erase now? Oh, my god! What am I doing? I’ve worked with trans people who were going through all kinds of transition while I’m…. And so, this fantasy of the permanent body, not to mention all my self-portraits. [unclear] [sighs, laughs] You know?

SCHILLACE: Right.

LEHRER: I just feel like…we… [sighs] we are moments in time.

SCHILLACE: Mm, mmhmm.

LEHRER: My whole book is about my intersection with medical history, or a lot of it is about where I collide at different points with medical history.

SCHILLACE: And as a medical historian, let me just say to my listeners, you will do well, historian readers, to pick up the book. You’ll be getting so much wonderful stuff in addition to the memoir. Sorry. OK, carry on. Just a little plug. [chuckles]

LEHRER: No, thank you. Thank you. I appreciate it. And you know, now, as you know, I work in medical humanities, and we are having all kinds of debates about the ethics of human display, for instance, at my university. And I’m very intent on trying to explain my position, which is not the popular one at all.

SCHILLACE: Right, right.

LEHRER: And it’s, I think, because I have a completely different sense of embodiment than the professors do or that, yeah. I mean, my reaction to human display and embodiment is to understand my body and to understand the bodies of the people I work with, which is very different from whether or not it pertains to my patient load or my prospective patients.

SCHILLACE: Right, yes.

LEHRER: And so, I see a completely different importance. And— No, please go on.

SCHILLACE: Oh no. I was just going to say there was a somewhat controversial museum display of polio patients in the nude a few years ago.

LEHRER: Where was that? I missed that.

SCHILLACE: Mentally, my brain is telling me Germany, but I don’t think that’s right either.

LEHRER: [inaudible]

SCHILLACE: I have to look it up. But it was essentially, it was quite controversial, and I was working in museums at the time. And it was controversial among museum staff, staffers as well because they thought, well, no, this is inappropriate. But the people had volunteered to have these nude photographs, and they were full size. So, when you walked through the display, they were the size of a regular person, and you walked through them in a hall to see their bodies displayed. And it does remind me a little bit of the way your art works in the sense that it was all quite, it was, it did not feel, people accused it of being a kind of gallery of, like a sideshow gallery or something.

LEHRER: Yeah.

SCHILLACE: And it didn’t feel that way at all. It actually felt as though these were engaged subjects who were asking you to look on and remember that the world is made up of— A disability scholar actually said this, and I can’t recall who it was, but that the world is made up of disabled and pre-disabled people, not disabled and abled people.

LEHRER: Yeah, I have a problem with that, though.

SCHILLACE: Oh, do you? Tell me about it.

LEHRER: There’s this thing—I don’t know what it’s from, I forget—but it’s called the witch at the wedding.

SCHILLACE: Uh-huh.

LEHRER: And it’s like, you’re the foreboding. You’re the which who’s here to cast the curse to, you know, your happiness is short-lived. Mortality is coming for you. I don’t wanna be that.

SCHILLACE: Yeah, yeah.

LEHRER: You know, I’m not gonna live my life as a threat to other people.

SCHILLACE: Right! right.

LEHRER: You know? I think that’s very, very shortsighted language, personally.

SCHILLACE: OK. No, that’s really powerful. I think that’s important to say. ‘Cause I think some disabled activists use it, I think, as a way of saying, you’re not so different from us. But I see your point because there’s a, it’s the stick versus the carrot, isn’t it? We want to explore our bodies in joy, not as horror.

LEHRER: Right.

SCHILLACE: So, I get what you’re saying, yeah.

LEHRER: I’m actually writing right now for, there’s a, I don’t know if you know Michael Sepal.

SCHILLACE: Oh, yes. I know Mike, personally, actually, and his wife is on the board of, it’s on our website.

LEHRER: Oh, that’s right. That’s right. Well, I’m writing, I just wrote a book chapter for Mike on this collection of nude scoliosis photographs they found at the Karolinska.

SCHILLACE: Mm, OK.

LEHRER: And you know, as someone who has scoliosis, he wanted me to, I think he wanted a very personal reaction to like, how does it feel to see this?

SCHILLACE: Right.

LEHRER: But I ended up writing about them in their relationship to both portraiture and queerness.

SCHILLACE: Right, right. Interesting.

LEHRER: And, you know, it just keeps reminding me that even, you know, the outside world keeps expecting disability to deliver a particular message of like, either we need help or we’re so pathetic or you’ll end up like this or something.

SCHILLACE: Mmhmm.

LEHRER: And I just continually find my aesthetics and my perspective so sideways to…everything?!

BOTH: [laugh]

LEHRER: Except for people like me. I don’t know.

SCHILLACE: No, I think that that’s really telling. And actually, it’s a great segue into another point I wanted to make about the book and about your work in general. And that is your commitment to beauty and joy, which I don’t think is always expressed, or in fact, isn’t even encouraged to be expressed. And I don’t— I’m actually, I have autism, which is a disability in many respects, and I’m also someone who’s non-binary. And so, I understand how much of that I was asked to hide or cover up for most of my life. And so, I didn’t treat it with the kind of, there’s a stained-glass wonderment of color in life that surrounds your artwork and also the words on the page, especially as you talk about intimacy and the right of disabled people to love, to have sex, to have children, to, you know, to live life at its fullest. And I think that’s something that makes your book, Golem Girl, so different from so many other stories, which are about rather than from.

LEHRER: Mm, mmhmm.

SCHILLACE: And I wondered if you wanted to say a few words about that. Because I do think that is one of the most critical and most beautiful aspects of the book, for me anyway, and of your perspective, of that sideways perspective, which I think lets the light in.

LEHRER: Well, I mean, we are people who are intensely aware of bodies…you know, or bodyminds. And we’ve had to understand. So, so, I’ve been writing about what I think disability beauty is, which I think partly answers this.

SCHILLACE: Mmhmm.

LEHRER: Which is that when people have been scrutinized most of their life, and it can be because of the way they look or the way that they perform their bodies or…. Yeah, I mean, perform your body covers a lot of territory, and that includes people who are queer and non-binary as well as people with impairments. Most of the time, you have to get to know yourself at a level that I think able-bodied people generally aren’t required to do. Whether or not they do, it’s not a requirement, and it is for us if we’re gonna survive.

SCHILLACE: Right.

LEHRER: And we do have this kind of double consciousness of understanding ourself and also constantly aware of the outside world’s picture, pictures, of who we are. And for me, this produces this kind of super-presence that I see, you know, sometimes I see in performers too, who I think get there through a different route. And that’s what really wows me is, and it’s just not something that you can point to and say, “There it is.” I mean. It’s something I see and experience and find really kind of lustrous.

SCHILLACE: Mmhmm.

LEHRER: And I think it goes to what you’re saying because once you’ve gone through all that, once you get to the point of love and sex and joy and…. I won’t say you don’t take anything for granted because that starts to sound like survivor language. I have mixed feelings about that too. I just think that you’re just there, like….

SCHILLACE: I wonder sometimes if it’s that I know I’ve had to learn, I’ve had to learn a lot about myself, as you point out.

LEHRER: Mmhmm.

SCHILLACE: I was late a diagnosis with autism. I just thought I was just weird as heck. Like, you know.

LEHRER: [chuckles]

SCHILLACE: You know, it was very difficult for me to read people. And I had Eric Garcia on.

LEHRER: Mm, mmhmm.

SCHILLACE: We were talking about [unclear] in his book. And I had to make human beings a study so that I could interact with the world as well as I do. And so, everything became a performance for me. Every, every aspect became a performance.

LEHRER: Yeah.

SCHILLACE: And so, I think some of it is sometimes, that’s called embodiment. For me, it was occasionally dissociative as well, almost disembodied. But it was a sense of entering into and a little bit like looking at your own brain, you know, as if you, as if your eyes could look at themselves. I feel like that’s kind of what it requires. And I think you’re right. I think you have to be there. You can’t, it’s not something you can kind of go on autopilot. You have to be there and you have to be looking and you have to be listening and you’re very present.

LEHRER: Exactly. That’s a perfect description. And I think that that is, that does something to you. It does something permanent to who you are. And sometimes I think when I hear people say, “Oh, I had this terrible illness, and it did all these dreadful things to my life, but I wouldn’t give it, I wouldn’t give it up for anything. Like, I would never, if I could say that would never, if I could undo it, I wouldn’t.” And I know that there’s a lot of narratives around that, but sometimes I think that part of it is this, and they don’t have language for it.

SCHILLACE: Mmhmm.

LEHRER: But it’s this, it’s a little like what art— OK, so the thing I tell my students about being an artist or a writer is that the big thing you get out of it is a conversation with yourself. That you get to know your own capabilities, limits, desires, imagination, place in the world in a way that I don’t have access any other way. I mean, that’s a different part of my life, but it so overlaps with the self-knowledge of disability, at least for me.

SCHILLACE: Yeah.

LEHRER: And, you know, I think that people who haven’t experienced that and then suddenly have this door fly open where they know themselves so much better, and they understand their, where they contact the world. I can see not wanting to give that up.

SCHILLACE: Yeah.

LEHRER: But I do wanna say something about, going all the way back to the beginning of our conversation, about having a book in a pandemic.

SCHILLACE: Mmhmm.

LEHRER: So, like I said, I was very hopeful. And I’ve seen these very terrible messages from mainstream culture and mainstream medicine about our lack of worth.

SCHILLACE: Right.

LEHRER: And as a Jew, [chuckles] you know, I certainly know the history of the “useless eater” rhetoric.

SCHILLACE: Mm, mmhmm.

LEHRER: And here’s what I am afraid of, and this is just no hyperbole at all.

SCHILLACE: Mmhmm.

LEHRER: But when I saw the kind of triage happening, I thought, OK, you know. As things went on, I thought, OK, COVID is ghastly, but COVID is also the faintest brush of the wing of what’s coming in terms of climate change.

SCHILLACE: Mmhmm.

LEHRER: And I mean, in part, COVID is a result of climate change, right?

SCHILLACE: Right.

LEHRER: You know, people going into animal reservoirs that we have no business in and coming back with, you know, party surprises. Guess what I’m bringing?!

SCHILLACE: [chuckles]

LEHRER: And I am very afraid that as the world moves towards either real or perceived scarcity, either real or failure-based scarcity, that I can see society moving more towards a picture where productivity is the ultimate.

SCHILLACE: Yes.

LEHRER: You know, and that, I mean, especially with—and I’m sorry if anybody out there disagrees with me, but—you know, I am…. [chuckles] Appalled is just so not the word, but what’s going on politically in America and around the world with the swing towards the right and towards fascism, and those are not paradigms that are friendly to disabled people!

SCHILLACE: No, no. Nor, well, yeah, to all sorts of people, but particularly that gets lost a lot, I find. I’m working on, my next book talks a little bit about this.

LEHRER: What’s it called?

SCHILLACE: It’s about the trans clinic in interwar Berlin as well.

LEHRER: Mm!

SCHILLACE: So, it’s about the rise of the Nazi Party and also the rise— So, it’s about homosexuality and other things like trying to have rights as this fascist sort of horrible things are on the rise at the same time and how that happens. But one of the things that routinely surprises people is when I tell them how many disabled people were killed in the concentration camps—

LEHRER: Oh, we were the test, crash test dummies, a key part.

SCHILLACE: Yeah. Absolutely. They were the first ones.

LEHRER: I mean, in America, it started in America—

SCHILLACE: It did. It did, mmhmm.

LEHRER: —killing off disabled people. And then it was, you know, an import.

SCHILLACE: And when not killing them, at least sterilizing them, which was practiced, you know, with impunity.

LEHRER: [unclear; cross-talk]

SCHILLACE: And so, that’s a story that has gotten lost. Yes, that’s true. But that’s a story that’s gotten lost. And by the way, just for our listeners, in case you weren’t sure: So, triage meaning they were trying to decide who got care in what order, and they were privileging certain kinds of lives over others because of scarcity of medical equipment. And we have some articles about that in the Journal if you need just a refresher on that. But what’s frightening about it is this sense that it’s happening, and it’s happening quietly. And people don’t recognize it for what it is, partly because those early stories, the beginnings of what happened before World War II have also been forgotten, the stories of how they treated disabled lives and sterilization process. Now you have them asking, you know, autistic people if they can put a “Do Not Resuscitate” on their medical chart.

LEHRER: [huge laugh] Oh god!

SCHILLACE: Yeah, it’s happening—

LEHRER: You know how often I’m asked?

SCHILLACE: So, it’s a really, we have a, we have, absolutely, it is imperative that all of us, all of us become aware of these. You’re right. It’s very difficult to look at these stories, but we need to remember them because we need to be able to recognize that some of these things are happening again right now all around us. And I agree with you. I think that there’s a real, we’re at a watershed moment where I feel like we are going to lose the opportunity to make those things, to make sure those things don’t happen if we don’t act pretty soon. So, again, another reason why Golem Girl is a really powerful and important book right now to be read. And I know it’s available widely in the U.S. It’s also available in the UK. Am I right? Yes?

LEHRER: Yes. Both paperback hardback, e-book, and audiobook.

SCHILLACE: Excellent. And so, I’m really excited. We are also having it reviewed, so the review will be linked as well on the Journal in the blog for those of you who also follow our blog as well as the print journal.

So, thank you so much. I know we’ve gone a little bit longer than I promised, but this has been an absolutely fascinating, necessary, and powerful conversation, again, Riva.

LEHRER: Thank you.

SCHILLACE: And if you haven’t already checked out her work, please go to her website. We will have a link on the blog to that that you can get to from this podcast and check out her work. It’s really amazing. Absolutely beautiful artwork as well. Riva, thank you for your inspiration and for your words, and for being with us today as part of the conversation.

LEHRER: Thank you. This has just been a joy.