Book Review by Dr Isabella Watts

Published by One World and Virago

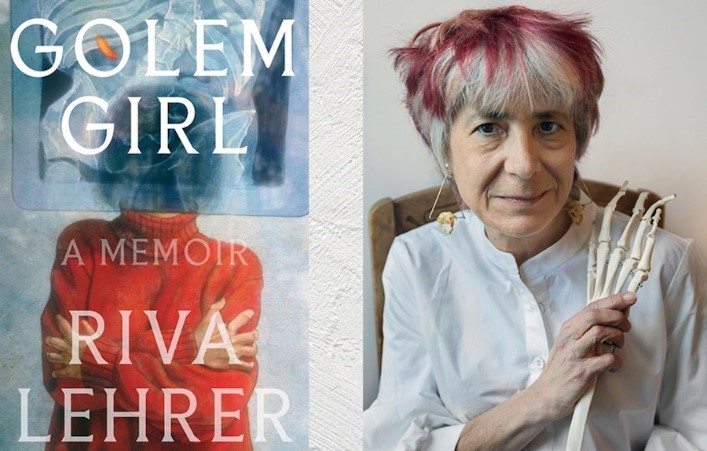

This book is the beautiful memoir the artist Riva Lehrer, detailing her experiences of life, love, and her engagement with disability culture. Born in 1958 Lehrer is diagnosed with spina bifida- a condition of the spinal cord which many infants at that time did not survive. She endures countless surgeries – many of which are experimental and goes on to become an artist whose work challenges the tropes that ableist society has of the disabled community. As a doctor I found this book both fascinating and educational. She expertly weaves together her experiences and those of her peers and includes historical and political references which make you aware of the prejudices of the time, and those that remain today.

This book is the beautiful memoir the artist Riva Lehrer, detailing her experiences of life, love, and her engagement with disability culture. Born in 1958 Lehrer is diagnosed with spina bifida- a condition of the spinal cord which many infants at that time did not survive. She endures countless surgeries – many of which are experimental and goes on to become an artist whose work challenges the tropes that ableist society has of the disabled community. As a doctor I found this book both fascinating and educational. She expertly weaves together her experiences and those of her peers and includes historical and political references which make you aware of the prejudices of the time, and those that remain today.

The opening sections of the book explore Lehrer’s childhood, and much is centred around her relationship with her mother. She spends the first two years of her life in hospital – until her mother can prove that the home environment will be suitable for a child with such complex needs. Her mother’s background in medical research and pharmacy no doubt has a part to play in the respect given to her by doctor’s and members of social service teams, but you are left wondering about the fate of those who do not have such a strong advocate. That Riva is able to thrive as a child is partly due to the loud voice and relentless activism of her mother, yet she explores how her mother often overwhelms her own choices. Lehrer explores their relationship unflinchingly – examining the complexities of a teenage daughter and mother, and how they are also impacted by her underlying medical condition as they jostle for power over decision making.

Another aspect of the relationship between the pair is that her mother is also troubled by back problems after a fall and a failed operation. Her mother’s pain mirrors hers and they are inextricably linked as Mrs Lehrer becomes rejected by society in different ways. Riva chronicles some of the human costs of the opioid epidemic and explores the societal lack of understanding about mental health at that time.

This examination of the medical world through the eyes of a different family member was fascinating. As a doctor I found Riva’s relationship with the healthcare staff eye opening. Many of the surgeries done on her were pioneering, but whilst several may have saved her life others seem to be cosmetic, pursuing a societal image of ‘normal’. Some of her relationships with doctors are positive– yet in others she is treated as less human than the rest of ‘able’ society and her choices are taken away. In particular I was shaken to read that she was given an emergency hysterectomy without being consulted. After this story she then explores the involuntary sterilisation of many people with medical disabilities throughout history.

As well as exploring her early interpersonal relationships she also describes her experiences of school and college. She attends the local Condon school which she describes as having a ‘radical philosophy that disabled children should get standard academic education’. Yet whilst she loves school, she also explores how she is slightly ashamed of being part of this community. Furthermore, she describes a disturbing encounter where a cover teacher at the school locks the classroom doors and tells the children that they are all the result of sins of their parents. Equally she describes worrying experiences of abuse that she does not truly understand at the time – with groping and exploitation in both the school and hospital environment. She couples this with stark statistics from the 2018 Shapiro report, indicating the high rates of sexual assault in those with physical and intellectual disabilities compared to the general population.

A theme that runs through the book is her relationship with her own body. It takes many years for her to even consider looking at her naked body – and this eventually comes from a liberating arts course where individuals must do naked self-portraits. You see the impact of societal commentary on her body image, and how she is constantly told that she is ‘less than’ and not feminine enough. In romantic relationships she also faces the judgement of those around her. When she has a 7-year relationship with someone from art college even her family tell her ‘if you really care for him then let him see other girls’.

As she learns more about her relationship with her own body and medical condition, she also branches into joining disability groups, and her artistic collaborations with these individuals run throughout the rest of the memoir. I found her journey of growth in these areas fascinating. She does not shy away from her initial prejudices around others in her community. I hugely respect the way she explores the language around disability and how other people wish to be referred to – and writes about her mistakes and her own internalised issues. This really encourages you as a reader to constantly learn and develop your understanding, highlighting that all of us are just a work in progress.

You learn about the vibrancy of her community, and she weaves her art into her writing. Her portraits are scattered through the pages, but you also learn about her artistic process and the stories behind the individuals in the work. She battles to make her work inclusive to the individual being painted, discussing her discomfort with the balance of power between the painter and the painted and how she fears that her scrutiny during painting mirrors the uncomfortable stares that her subjects get from the public. As someone who teaches a medical humanities module on ‘medicine in literature’ I loved that she talks about the medical humanities module that she runs, which teaches fine art and portraiture to medical students and explores subjects such as disability – hopefully helping students to begin questioning the prejudices that many of us unconsciously internalise.

This book is a beautiful exploration of her life and her understanding of her medical condition and its impact on her life. It teaches you about art and its colourful cultural scene, as well as the important work of the Disability Arts Collective she starts working with. Lehrer explores medical and social models of Disability and forces you to confront harsh realities about our ableist society. She ends the book with a sombre epilogue about the effects of the pandemic on the disabled community, and how their care plummeted down the priority list. She highlights the importance of radical visibility and leaves you with a desire to further educate yourself.

Izzy Watts is an academic foundation programme doctor at St George’s University Hospital. She is a keen reader and passionately believes in combining medical education with the Arts subjects.