Blog by Sathyaraj Venkatesan

The present piece offers a brief graphic analysis of two COVID-19 related folk painting representing two major artistic traditions in India—patachitra and mithila—in order to demonstrate how these paintings, through using Hindu religious codes and stories, imagine the current pandemics. Before I do so, it would be instructive to offer a brief background of these art traditions.

Patachitra and Mithila: An Introduction

Patachitra and mithila are the oldest visual art forms in India, though they are different in terms of their orientation, style, origin, practice, and materiality. Patachitra is a combination of two words—pata (fabric/scroll) and chitra (drawing or painting)—and means drawings on woven fabrics or scroll paintings.1 Produced by chitrakars (producers of paintings) and practiced predominantly in Bengal and Odisha in India, patachitras address religious themes but also issues of socio-cultural importance. On the other hand, mithila paintings produced mostly by women in the Mithila region of Bihar in India illustrate Hindu deities and lesser-known traditions as described in the Vedas, the Ramayana, the Mahabharata, and Krishnalila among others. They mostly use eco-friendly dyes and are typically finished in black lines on cow dung treated paper.

Recycling Hindu stories

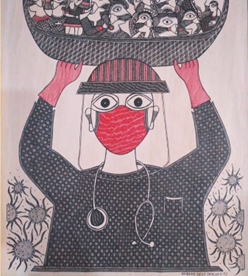

Drawing from the conceptual categories of superheroism, sacrality, and Hindu religious stories, multiple-award winning folk artist Ambika Devi’s Tribute to the Doctors maps the story of the birth of Lord Krishna (an avatar of god Vishnu) to the current situation. There are several such instances of re-purposing religious myths and legends across the globe—Jonathan Muroya, an illustrator based in Providence, for instance, deftly uses Greek gods and the associated myths to capture several aspects of life during the pandemic in his “Greek Quarantology” series. Ambika Devi’s work alludes to the story of Krishna as told in Krishna Charitas. Vasudeva (father of Lord Krishna) carries baby Krishna in a basket held above his head as he crosses river Yamuna to save baby Krishna from Kamsa, a tyrant ruler of the Vrishni kingdom, who is determined to kill all the children of Vasudeva and his wife Devaki. Though Kamsa succeeds in killing seven children of Devaki, Vasudeva manages to rescue his eighth son, Krishna and brings him to the village of Gokul. Marked by intricate fine line work using red and black colors in handmade paper, Tribute to the Doctors secularizes the birth story of Krishna through inserting a masked doctor wearing a stethoscope in the place of Vasudeva. While Vasudeva carried baby Krishna in a basket above his head and thus saved the newborn from Kamsa, in the painting, it is a physician who carries a group of people in a basket to save them from coronavirus (see virus icons around the physician’s coat). This painting pays homage to doctors and bestows divinity and sacredness to them. Hindu stories are re-circulated, refashioned and secularized here to convey the superheroic interventions and exemplary work done by the physicians who save not an individual (as in the story) but humanity at large from infection and death. This mapping and re-coding of a religious story to the current moment helps the artist to celebrate the extraordinariness and persistence of the doctors amidst challenging times. The painting is also glocal in that it joins other visual arts in paying tribute to the frontline workers but also remains local and quintessentially Hindu through the way it utilizes the rhetorical context and traditions of the religion.

COVID-19 Demon

Corona Rakshasa by Bengal chitrakars Rupsona and Bahadur Chitrakar portray coronavirus as a rakshasa. Rakshasas (as opposed to gods) in Dharmic religions are malignant demons who are capable of consuming human beings and shifting shapes. Like vampires and medieval monsters in Western mythology, rakshasas are wicked beings with a terrifying appearance who constantly come into conflict with human beings and saints. Rupsona and Bahadur Chitrakar’s painting offers a close-up view of corona rakshasa with long fingernails, horns, and corona-stricken body and eyes. The painting is presented predominantly in red color and is invested in the Hindu mythology of asuras (ungodly beings) not only to suggest the monstrosity and the horror that the virus triggers in contemporary real life but also to imply how the virus, like a typical rakshasa, feasts on the blood of helpless victims. While corona icons and sun-looking motifs fill the border of the panel with geometrical regularity, a flying dragon and a multi-coloured earth in the foreground suggests the Chinese origins of the virus and the planetary nature of the pandemics. In short, the painting concretizes corona as a rakshasa to convey the lethal and the atavistic force of the virus. In so doing, Corona Rakshasa, described in the visual language of Hindu religion, provincializes and thus offers a cultural/folk alternative to the widely circulated clinical image of the virus.

Uses of Religion in Times of COVID-19

Resorting to religion and art is a standing reserve and a natural human response to fear, uncertainty, and existential angst caused by the pandemics. They have time and again reinforced the power of good over evil and thus the cathartic, coping and reassuring functions of the same. The paintings discussed here repurpose and weave the Hindu religious imageries, stories of the Hindu celestial gods and extraordinary acts of ordinary people with the COVID-19 pandemics not only to map the cultural anxieties occasioned by pandemics but also to offer the much-needed hope and confidence during the coronavirus pandemic. Also, these folk paintings are textured biocultural sites which demonstrate how COVID-19 is not a mere medical/epidemiological event but is also constituted and constantly negotiated within socio-artistic and religious matrices. These paintings, in short, are a testimony of such functions and meaning-making practices and thus, contribute to the collective grand narrative on contagion.

Works Cited

[1] Chatterji, Roma. Speaking with Pictures. New Delhi, Routledge, 2012.

Sathyaraj Venkatesan (sathya@nitt.edu) is Associate Professor of English at the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences in National Institute of Technology, Tiruchirappalli (India). His research concentrates on graphic medicine, literary health humanities and American literature. He is the author of eight books and over ninety research articles. His recent co-authored eighth book is Metaphors of Mental Illness in Graphic Medicine (New York/London: Routledge, 2021). Currently, he is co-editing a book titled Pandemics and Epidemics in Cultural Representation (contract under Springer Nature).