Blog by Michaele Francesco Corbisiero, Violette Simon and Carlos Franco-Paredes

On April 28, 1996, a gunman in Australia killed 35 people at a tourist site in Tasmania. Only 12 days later, Prime Minister Howard announced major reforms on Australian firearm laws.1 The government bought back 650,000 guns and the remaining civilian firearms were registered to new national standards.1

Australia has not experienced a mass shooting since then.

More recently, the attack at two mosques in Christchurch, New Zealand catalyzed major gun reform. In less than 24 hours, Prime Minister Ardern announced stricter firearm laws and the government swiftly approved the Arms Legislation Bill despite a strong gun lobby, similar to the one in the United States.2

In other countries, mass shootings have also powered significant reform – with positive results.3

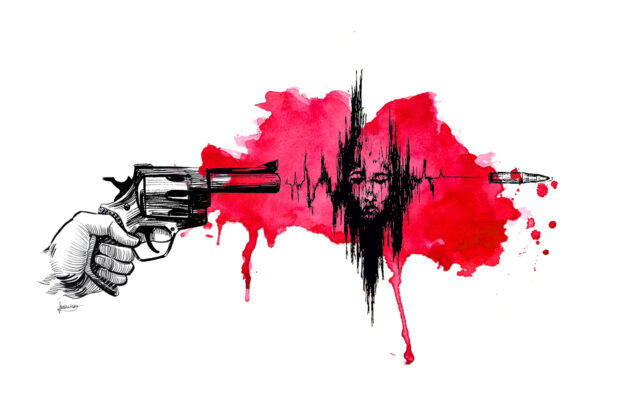

The recent mass shootings in Atlanta and Boulder highlight the chronic gun violence in the United States. In fact, gun violence is an American epidemic and like any public health crisis, it demands a coherent public health approach.4

For health professionals, gun violence is about patient health. Unfortunately, treating victims of gun violence has become commonplace, and physicians in the US are trained for it. But instead of a reactionary response to this carnage, physicians must step up their leadership of preventive measures.

The National Medical Association, the American Medical Association, and the American Public Health Association have issued policy statements on gun violence and the role of healthcare professionals. This would not be the first time that physicians notice a health crisis and take action. Physicians were instrumental in creating recommendations that influenced reforms on alcohol and driving.5,6

When considering how to manage the gun violence epidemic, it’s important to understand the scale of the problem. The Second Amendment is a major consideration, as is the polarized political system and the power of the gun lobby. The United States has more guns than any other industrialized country. In fact, there are over 300 million guns in the US – more than one gun for every resident.7 According to a study by researchers at the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, gun ownership is linked to more gun violence.8 States with more guns have more gun deaths.8 This relationship is the same in other developed countries: nations with more guns had more gun violence.9,10 Less well known is that most gun deaths are suicides.11 The key reason is the lethality, or effectiveness, of guns compared to alternatives.12 As such, reducing access to guns is an important strategy to prevent suicide by reducing access to lethal means.12 Given the complexity of gun violence in the United States, no single policy would be adequate to control the threat to public health. For this reason, using automobile safety as a model, a comprehensive approach is needed to reduce gun violence and improve gun safety.

We suggest five practical, data-driven interventions to reduce gun violence:

(1) Expanding background checks: Only 22 percent of guns purchased in the US are obtained with a background check.13 Research, while preliminary, suggests that background checks are associated with reductions in firearm deaths.14

(2) Promoting Safe Storage: Some countries require gun owners to store guns and ammunition separately, as well as requiring trigger locks. These practices were all associated with reduced gun violence, reduced youth suicide, and reduced unintentional firearm injuries.15,16

(3) Gun Training: Licenses for gun ownership focused on safety will prevent unnecessary death and injury. Switzerland is a great example. The rate of gun ownership is high, as in the United States, but gun training and safety is emphasized and integrated into their culture.17

(4) Implementing Protection Orders: Individuals with a criminal history of any violence should not be permitted to have firearms. Many states have red-flag laws that prevent access to firearms if a household member or law enforcement officer believe that an individual poses a threat to themselves or others.18 Recent research shows that red flag laws prevented 21 high-risk mass shootings incidents in California and reduced the suicide rate by 13.7% in Connecticut.18,19

(5) Fostering further research Initiatives: Research on gun violence prevention is underwhelming. In 1996, the Dickey Amendment stopped federal funding on firearm research.20 An article in JAMA looked at the amount of funding for various injury and disease conditions compared to the mortality burden. Firearm injury has approximately the same mortality rate, around 10 or 11 per 100,000, as sepsis.21 And yet, it receives less than 0.8% of the funding that sepsis research.21

Physicians are witnesses to the cycle of individual and societal devastation that gun violence causes. We have a duty to advocate for evidence-based, data-driven reform. Medical professionals were pivotal in driving common-sense changes in the automobile industry that has saved over 600,000 lives in the past 75 years.22 Now it’s time to channel our energy and contribute to long-term and permanent reductions to the catastrophic consequences of gun violence.

References

- Peters, R., & Watson, C. (1996). A breakthrough in gun control in Australia after the Port Arthur massacre. Injury Prevention, 2(4), 253.

- Schwartz MS. New Zealand passes law banning most semi-automatic weapons. 2019. Available at: npr.org/2019/04/10/711820023/new-zealand-passes-law-banning-most-semi-automatic-weapons. Accessed April 2, 2021.

- Parker, S. (2011). Balancing act: Regulation of civilian firearm possession. Small arms survey, 1-91.

- Taichman, D. B., Bauchner, H., Drazen, J. M., Laine, C., & Peiperl, L. (2017). Firearm-related injury and death: a US health care crisis in need of health care professionals. Jama, 318(19), 1875-1875.

- Borkenstein, R. F., & Smith, H. W. (1961). The breathalyzer and its applications. Medicine, Science and the Law, 2(1), 13-22.

- Maskalyk, J. (2003). Drinking and driving. Cmaj, 168(3), 313-313.

- Karp, A. (2018). Estimating global civilian-held firearms numbers(pp. 1-12). Geneva, Switzerland: Small Arms Survey.

- Kalesan, B., Villarreal, M. D., Keyes, K. M., & Galea, S. (2016). Gun ownership and social gun culture. Injury prevention, 22(3), 216-220.

- Alpers, P., & Wilson, M. (2013). Global impact of gun violence: Firearms, public health and safety. Sydney School of Public Health, The University of Sydney, August, 14.

- Naghavi, M., Marczak, L. B., Kutz, M., Shackelford, K. A., Arora, M., Miller-Petrie, M., … & Tran, B. X. (2018). Global mortality from firearms, 1990-2016. Jama, 320(8), 792-814.

- Miller, M., Lippmann, S. J., Azrael, D., & Hemenway, D. (2007). Household firearm ownership and rates of suicide across the 50 United States. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery, 62(4), 1029-1035.

- Fleegler, E. W. (2020). First, prevent harm: eliminate firearm transfer liability as a lethal means reduction strategy. American journal of public health, 110(5), 619-620.

- Miller, M., Hepburn, L., & Azrael, D. (2017). Firearm acquisition without background checks: results of a national survey. Annals of Internal Medicine, 166(4), 233-239.

- Sen, B., & Panjamapirom, A. (2012). State background checks for gun purchase and firearm deaths: an exploratory study. Preventive medicine, 55(4), 346-350.

- Crifasi, C. K., Doucette, M. L., McGinty, E. E., Webster, D. W., & Barry, C. L. (2018). Storage practices of US gun owners in 2016. American journal of public health, 108(4), 532-537.

- Grossman, D. C., Mueller, B. A., Riedy, C., Dowd, M. D., Villaveces, A., Prodzinski, J., … & Harruff, R. (2005). Gun storage practices and risk of youth suicide and unintentional firearm injuries. Jama, 293(6), 707-714.

- Rosenbaum, J. E. (2012). Gun utopias? Firearm access and ownership in Israel and Switzerland. Journal of public health policy, 33(1), 46-58.

- Kivisto, A. J., & Phalen, P. L. (2018). Effects of risk-based firearm seizure laws in Connecticut and Indiana on suicide rates, 1981–2015. Psychiatric services, 69(8), 855-862.

- Wintemute, G. J., Pear, V. A., Schleimer, J. P., Pallin, R., Sohl, S., Kravitz-Wirtz, N., & Tomsich, E. A. (2019). Extreme risk protection orders intended to prevent mass shootings: a case series. Annals of internal medicine, 171(9), 655-658.

- Rostron, A. (2018). The Dickey amendment on federal funding for research on gun violence: a legal dissection.

- Stark, D. E., & Shah, N. H. (2017). Funding and publication of research on gun violence and other leading causes of death. Jama, 317(1), 84-85.

- Kahane, C. J. (2015). Lives saved by vehicle safety technologies and associated Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standards, 1960 to 2012–Passenger cars and LTVs–With reviews of 26 FMVSS and the effectiveness of their associated safety technologies in reducing fatalities, injuries, and crashes. Report No. DOT HS, 812, 069.