Sherine Hamdy and Coleman Nye (writers), Sarula Bao and Caroline Brewer (art), Marc Parenteau (lettering), Lissa: A Story About Medical Promise, Friendship, and Revolution (2017), University of Toronto Press, 302 pp, £12.99.

Reviewed by Dr Glyn Morgan

Lissa is the first book in a new series from University of Toronto Press with the punningly pleasant title of ethnoGRAPHIC: a collection of ethnographies written in the form of graphic novels. I have to say that if they’re all of similar quality to Lissa then it will be a series to keep an eye on. Lissa is a fictional story based on hours of interviews, extensive research, surveys and studies by the authors Sherine Hamby and Coleman Nye. Hamby is Associate Professor of Anthropology at the University of California, Irvine; Nye is Assistant Professor of Gender, Sexuality, and Women’s Studies at Simon Fraser University in British Columbia. The principal characters are composites, allowing the authors to tell real stories without compromising identities or medical histories, but many of the secondary and background characters are real individuals; this is particularly true of the parts of the book set in Egypt.

Lissa is a graphic novel about the friendship between two teenage girls: Anna and Layla. Anna is a white American with a love of photography, living with her family in Egypt and attending an American International school at which her mother teaches, and her father works for an oil firm. Layla is an Egyptian Arab, attends an Egyptian school, and her father is the bawab (doorman or porter) for a building which is home to moderately well-off Egyptians. At the beginning of the novel these two are closest friends, they play cards together and pull pranks on the haughty woman who owns Layla’s building. However, it quickly becomes clear that their relationship will face serious tests. Many of these are typical of what we might expect in a story of this type: the two girls as they grow up face different pressures, as society has different expectations of them. What makes the book stand apart, however, are the complications to their relationship which detonate with dramatic and lethal implications: complications both medical and political. It probably goes without saying that one of the core realisations that both girls have to eventually confront is that those two complications are intertwined.

As the novel opens, we learn that Anna’s mother has had breast cancer, that the cancer has returned, and that her chemotherapy isn’t working. Ultimately, Anna has to deal with the loss of her mother and the knowledge that she is a girl growing up with a family history of breast cancer (her mother’s sister also died from the disease). Anna’s father is rarely shown in the art of the novel, he is often obscured, out-of-focus, or cropped out by the placement of the panel’s frame. Anna, returning to the United States, descends down a medical rabbit hole researching the BRCA1 mutation, ignoring her friends and spending increasing amounts of time in cancer support groups. Meanwhile, back in Egypt, Layla’s father Abu Hassan develops severe kidney disease and is placed on dialysis, his only hope of returning to anything resembling a normal life is an organ transplant. Abu Hassan refuses to accept a donation from his children and, even if they could convince him, his son is rejected as a possible donor having contracted Hepatitis C regardless. With no donor register in Egypt, the family are reliant on finding ‘some desperate person’ who would be willing to sell their kidney, not that they could afford to pay such an individual (126). At the same time, Layla’s parents are more willing to put their faith in Koranic wisdom rather than their doctors. In persuading his children not to donate organs, Abu Hassan tells them that ‘God, in His Perfect Wisdom, created us whole. We cannot give away what is not ours to give’ (110). Both girls have to learn to deal with their grief, and to navigate the financial waters of American and Egyptian healthcare. The authors throw them into contrast by having the two girls approach their medical problems from opposite economic and cultural directions, as Layla tells Anna whilst trying to convince her not to get a preventative mastectomy, ‘Here [in Egypt] we don’t have enough medicine. There [in the United States], you’ve got too much’ (119). Yet, the book leaves no doubt that there are as many points of comparison as there are points of contrast.

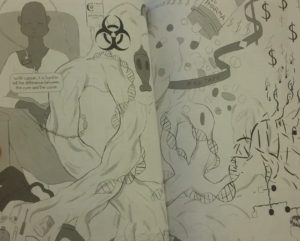

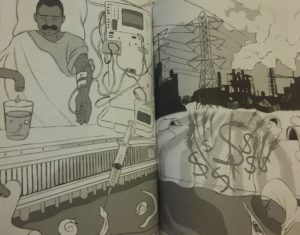

Double splash pages of Anna and Layla confronting the realities of medicine in their respective countries, both girls can be seen as the bottom-right corner of their respective pages, overwhelmed and drowned-out by the issues facing them: big pharma, environmental toxins, genetics, and of course in both cases: money.

Whilst facing these deep personal dramas, Layla and Anna are swept up in another tumultuous event: the 2011 Egyptian Revolution against the rule of Hosni Mubarak. The backdrop of the revolution further complicates the two girls’ medical dilemmas, particularly for Layla. The book presents a citizen’s view of the revolution; specific details and the factional politics surrounding the protests are sparing, however Layla volunteers with the medics who treat the protestors and so we are presented with vivid and powerful sequences showing the selflessness, bravery, and heroism of the Tahrir Square doctors. Given the visual dimension a graphic novel brings to the narrative, the addition of revolutionary graffiti is particularly welcome. Graffiti artists were omnipresent and powerful spokespeople of the revolution and the last sections of the book reproduce a number of artworks, where possible crediting the artists responsible. As the revolution progresses it takes its toll on both girls, not only causing them to shed any last vestiges of innocence about the realities of the world, but also stretching their relationship even further towards breaking point. Ultimately, both girls have to face up to the imperfections of a revolution which became increasingly factionalised and affected little real change, and the inability of medical systems to provide all of the answers.

Ultimately, the story of Anna and Layla is a sweet coming-of-age narrative wrapped around their mutual medical concerns, made more fascinating by the backdrop of the Egyptian revolution. As the realities of the revolution begin to become apparent, the book’s title, Lissa, is presented as a notion of hope for the future (within the text it is translated from Arabic as “there’s still time”), but there are sources of frustration within the story which complicate this optimism. Loose-ends abound, such as the future facing Layla’s brother who is maimed in some of the violence of the revolution. Anna’s relationship with her father seems to improve in one vital scene where he finally steps fully into a panel, but he recedes again and is absent from the narrative entirely whilst his daughter puts herself in danger in revolutionary Cairo. Yet, such threads, frustrating though they might be, add to the realism of the text and are likely drawn from the real lives which inform the characters. Real lives never wrap up neatly, after all. More disappointing is that the art of the book only inconsistently matches the vision of its narrative. Some pages are powerful and beautiful in equal measure, and the aforementioned inclusion of Egyptian graffiti is to be highly commended, but other pages – often more banal in their narrative content – are let down by the book’s simple style. Simple artwork can be striking when used to draw attention to the text’s narrative, or to moments of complexity. In Lissa, the art is sadly sometimes inconsistent in its quality, and unnecessarily jarring in places.

The book closes with sixty pages of supplementary material, which are what truly make Lissa stand out as a work of anthropological ethnography versus similar graphic novels. Whilst I’m a firm believer that a comic book need not rely on pages of conventionally printed text to achieve its aims, the material provided with Lissa adds immense value to the text, improving accessibility for all readers. These pages include detailed breakdowns of some of the art in the book, including an essay of analysis by cartoonist Paul Karasik which amongst other things provides a lesson in the fundamentals of reading a graphic novel’s art as part of the narrative with its own meaning. There’s a timeline of the revolution for anyone who wasn’t following news of the so-called Arab Spring in 2011 and needs more information to understand what events Anna and Layla are referring to. There are Q&A interviews with the book’s creators on their research, the process of creating a graphic novel, and the medical realities behind the stories (amongst other things). Finally, there are teaching guides with suggested discussion topics, prompts for teachers and book clubs, and further reading on the Egyptian Revolution, Cancer, Transplants, and Comics and Medicine. These pages supplement a graphic novel which is already an interesting and enjoyable text, and make it into a truly noteworthy addition to the burgeoning field of graphic medicine, bioethics, and medical memoir.