This blog post is from Prof Desmond (Des) O’Neill, a geriatrician and cultural gerontologist. O’Neill is a Professor in Medical Gerontology and co-chair of the Medical and Health Humanities group at Trinity College Dublin, Ireland.

Wikipedia is a marvellous source of information but its open structure leaves it vulnerable to practical jokes. An entertaining example is associated with the bicentenary this year of one of France’s most celebrated composers, Charles Gounod. The entry states that the composer Saint-Säens improvised on a song by Gounod called “What will we do with this pumpkin stew?” at his funeral. In reality, his funeral in 1893 was an imposing event, attended by the great and the good, but the music was altogether more conventional. Gounod and his widow had specified plain chant only, with fellow composers Fauré and Saint-Säens improvising from his great religious oratorios Mors et Vita and Redemption on the organ. A favourite composer of Queen Victoria, his prominence in British life in the late-19th century has a link to the British Medical Association. While Charles Dickens’ residence from 1851 to 1860 at Tavistock House is celebrated by a Blue Plaque on BMA House, few are aware that Gounod also lived there from 1871 to 1874.

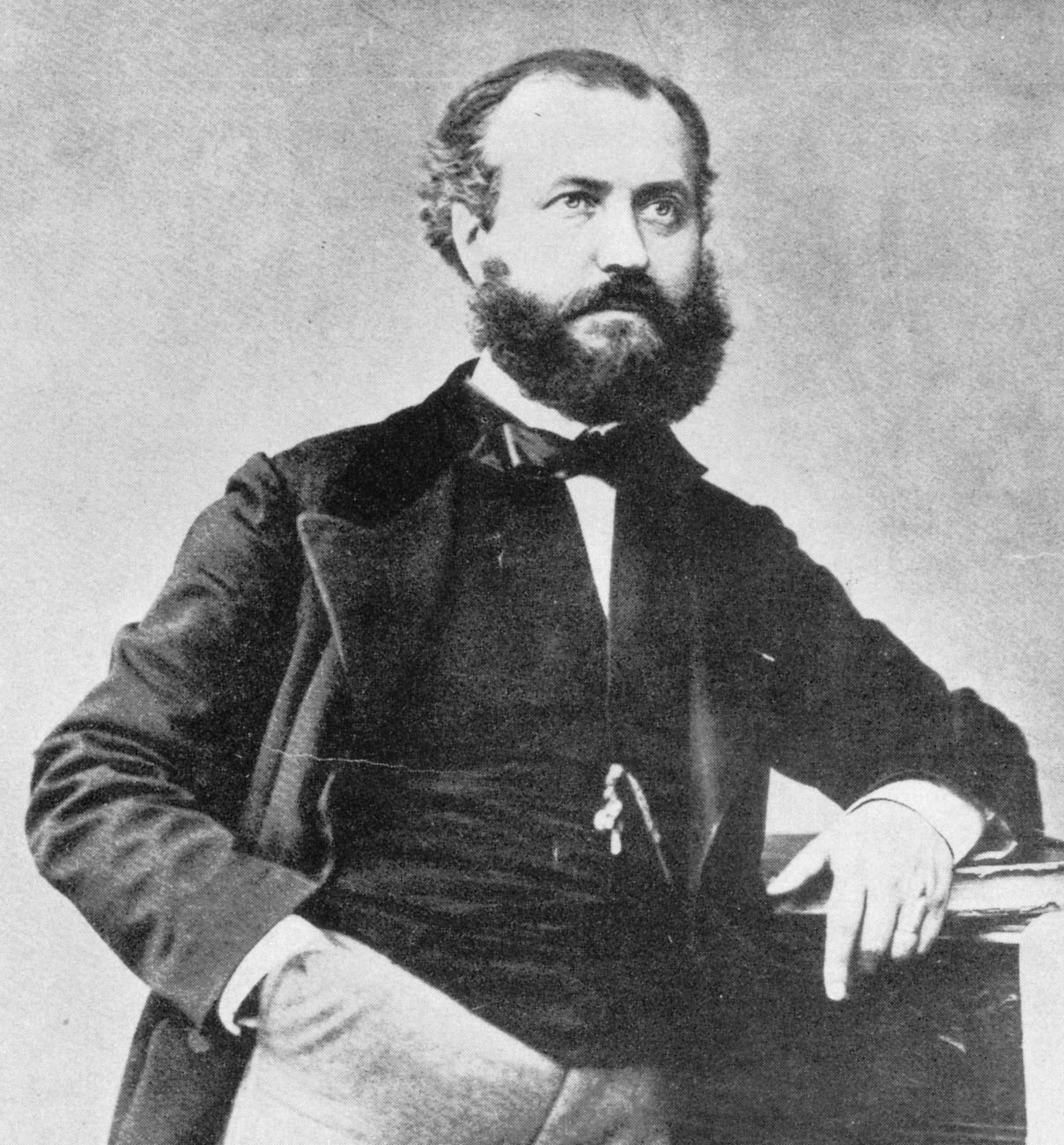

His life was as varied, individual and sometimes contradictory as his music. An early dalliance with entry to Holy Orders reflected his deeply-held Catholic faith. However, he was also notable for the ease with which he moved in the social circuits and salons of 19th century Paris, numbering Turgenev, George Sand, and the celebrated singer Pauline Viardot among his circle. In addition, he had close relationships with a number of women, one of which would lead to a celebrated scandal in London.

In his youth he won the prestigious Prix de Rome, making a particular link with Mendelssohn, whose style would emerge in later years in Gounod’s work, a precedence for elegance over brutality and unbridled passion. One French critic described Gounod as combining the pure simplicity of Mozart with the troubling poetry of Schumann. His career was anchored by his appointment in 1852 as director of the Orphéon, a network of choral societies unique to 19th century France, supported financially by municipalities and with membership drawn from the working class and lower bourgeoisie, a reflection of egalitarian social policy in the Second Empire. After a slow-burning start, his opera Faust was his major breakthrough on French and international stages, bringing celebrity and further commissions. Almost equally successful were his operas Mireille and Roméo and Juliette, and his Ave Maria based on a Bach prelude: according to Saint-Säens, “all women sang his songs, all young composers imitated his style.”

A rupture occurred with the Franco-Prussian war when he and his family decamped to London. Composing with fresh vigour, he found a responsive audience among the English public, particularly for choral works. He was invited to compose a choral piece for the opening of the Royal Albert Hall: its success led to an invitation to direct the large choral society associated with the famous venue. However, he then lodged in Tavistock House with an amateur singer, music teacher and subsequent celebrated litigant, Georgina Weldon. His wife returned to France in high dudgeon and Gounod spent three years in the Weldon household, refusing enticing offers in France such as the directorship of the Conservatoire. Eventually stung by increasingly scandalous newspaper reports of this arrangement, he fled when Mrs Weldon was out of the house: she retained his papers and some scores, which he was not to regain for many years.

His subsequent career was notable for the enormous popularity of his oratorios La Rédemption and Mors et Vita, particularly in England. He conducted the première of the former, dedicated to Queen Victoria, in Birmingham in 1882 with a choir of 270: due to a successful libel suit by Mrs Weldon he could not return to do the same for Mors et Vita.

Gounod is remembered now by works representative of his broad range, from the delightful Mass of Saint Cecilia through the deeply moving Mors et Vita to the exuberant musical mosaics of Faust and Roméo and Juliette: his Funeral March for a Marionette is associated in most minds as the theme music for Alfred Hitchcock Presents. In his bicentenary year, it would be fitting for the BMA to consider erecting a companion plaque to that of Charles Dickens to celebrate the residence of this most gifted of composers.