Today’s guest blog post comes from Rebecca Marshall who has just graduated from UCL Medical School having intercalated in Global Health. She is currently undertaking an MSc in Medical Anthropology (also at UCL). Her main interests include the intersections between medical anthropology, global health and bioethics. Here she writes about Wings, a recent play showing a female pilot recovering from stroke and compares this to the real-life story of RAF pilot Joy Lofthouse, as well as some of her own experiences as a medical student on the hyper-acute stroke ward.

It’s the nearest thing to having wings of your own.

Suspended from the air, Juliet Stephenson’s character Emily, transports us through the fragmented parts of her consciousness. Acrobatic tumbles from a trapeze. Echoes of a tumultuous set of memories. Piece by piece, she tries to string together her reality; all on the backdrop of a dystopian hospital set. The three acts are symbolic of her own path to recovery: I – Catastrophe, II – Awakenings and III – Explorations. Arthur Kopit’s play Wings (staged at the Young Vic) allows us an insight into a patient’s struggle after suffering a stroke; specifically affecting her memory and language domains. She is showing symptoms of both ‘expressive and receptive dysphasia’, anatomical neighbours in the brain’s regional map’

Act 1 opens with scenes in which Emily’s recognition is tested under the auspices of the hospital ‘Mini Mental State Examination’; Can you tell me the date today? What is this called? Do you know where you are? – alas she fails to find the words of common objects and to orientate herself. The audience is allowed a snapshot into this failure, her painful struggle; the struggle to find words and the battle to find herself amidst the chaos. At one point she asks ‘Where’s my arm? I don’t have an arm! What’s an arm?’. These hospital scenes are juxtaposed with memory flashbacks to her time as an RAF pilot. She comes perilously close to crashing but ‘then all at once – I remembered everything’; her motor memory kicks in, her arm steers the wings and she soars. In the following two acts, we follow Emily’s journey to a rehabilitation ward and the moving encounters between language therapist and patient. Mechanics of neural plasticity, the rewiring of the brain, as it begins to rediscover words and meanings. Tears; tears of joy, of misery. And as she begins to relearn words, to put meanings to objects and subjects; she’s piecing together her sense of self. With a large CT scan of her brain floodlit across the stage set; the neurological diagnosis, the focal lesions and pathological terminology – are set against the mystifying and complex understandings of a ‘stroke’.

It just so happened, a week after seeing Wings at the Young Vic, that I serendipitously stumbled across an obituary in The Times of Joy Lofthouse. Joy, who sadly passed away aged 94, had been a World War II ferry pilot, forming part of the ‘Attagirls’ group. In the context of world war political upheavel, a time when gender dynamics were subject to dramatic changes, 160 women were trained to deliver RAF and Royal Navy planes from factories to airfields under the Air Transport Auxilary, allowing male pilots to be enlisted on the front line. Remarkably, Joy Lofthouse was one of the first women to fly a Spitfire. Mrs Lofthouse described the changing role of women amidst war-torn Britain before she passed:

It was the best job to have during the war because it was exciting, and we could help the war effort. In many ways we were trailblazers for female pilots in the RAF. Wartime gave women something they’d never had: independence, earning your own money, being your own person. You have to remember that as young girls, the emphasis for us had always been on marriage and children. So being able to go into the forces to be taught to fly was virtually undreamt of. To be honest, I wanted the war to go on as long as possible.

And as she movingly recounted: ‘It’s the nearest thing to having wings of your own’.

I couldn’t help but think of the intertwined narratives of Emily and Joy Lofthouse, two wing walkers together.

Yet as I, amongst a captivated audience, watched Emily’s plot unfold, listening to her rediscovery of language, I found myself transported back to a memorable case on the Hyper-Acute Stroke Ward.

As part of my Neurology rotation as a medical student at Queen Square, we were set the task of presenting cases in one of the grand, wooden lecture theatres. Case presentations can often be intimidating tasks, learning how to piece together stories and clinical histories in a coherent and useful way and Hoping, with a capital H, that the case provides some useful learning points; a leaning to the weird and wonderful oft recommended. A hectic ward round on the HASU was certain to provide me with ample cases to pick from.

Yet, a major challenge in the case of stroke patients, lies at the epicentre of the nature of neurological diagnoses. Patients who have suffered an infarct, specifically to the speech areas of the brain, often make for poor historians. Reliant on perceptive observation, scrutinising neurological examinations and evidence on brain imaging scans, the team is set the task of piecing fragments together quite apart from the patient.

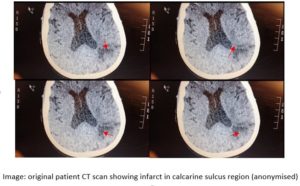

Nevertheless, on this particular hectic ward round, the Consultant turned to me to take a brief history from one of our patients. She was complaining that her ‘glasses were dirty, her world foggy’. The consultant turned to me and asked, ‘So how are you going to proceed?’. I was umming and arring about what I should do. Do I proceed to a detailed neuro-visual examination? Or should I follow my instinct and try cleaning her glasses first? Alas, I fell into the trap and tried first, to clean her glasses. Yet as I could sense a few chuckles from the team and the rather unimpressed look on the consultant’s face, I thought I had better persevere with a visual examination. It was probably owing to a combination of my own nerves and poor examination technique; but I couldn’t detect any signs. The team then brought up her brain scan on the monitor; comparing old with new. This showed evidence of an old infarct (in the parieto-occipital regions) and her most recent CT scan showed evidence of a new infarct in the calcarine sulcus (a key area for vision). The Consultant carefully explained to myself and the other student how crucial careful examination was in piecing together stroke diagnoses. ‘She has a right sided homonymous hemianopia. Go back and examine her speech too; then come and present her case to me with your overall findings.’

As I journeyed back to our patient, I found it difficult even to begin with a speech assessment. She appeared confused and quite distressed. As we tried to persevere with a speech and language assessment it became apparent that, just like Emily, she was displaying both expressive and receptive dysphasia. Of course, her visual field defect likely would also impact her ability to recognise and name objects. But she was also incoherent, not producing speech fluently (the expressive dysphasia), and she had word-finding difficulties (the receptive dysphasia). She was able to recount small fragments to us; she lived alone and had high blood pressure. Yet her Mini Mental State Examination was 3/10. She was disorientated in time and place. We could see from her drug chart that she was on medication for high cholesterol and depression.

Presenting back to our Stroke Team turned out to be an eye-opening experience. Whilst focal infarcts on CT scans and clinical examination could point towards the diagnosis – the uphill battle had only just begun. The Catastrophe was unfolding. Yet the next two acts, Awakening and Unfolding, were where recovery might lie. Rehabilitation post-stroke is one of the most daunting challenges facing patients and medical teams alike. Our patient had extensive visual and language deficits, a background of clinical depression and risk factors for subsequent strokes and small vessel disease. As we discussed the case it became important to reflect on our patients opening words ‘dirty glasses’…’a foggy world‘. It would be impossible to decipher how much of this was due to a visual field defect and how much apportioned to confusion or her psychological outlook. Her words and use of language became key in understanding the complexities of her case; yet also the importance of multidisciplinary rehabilitation – from medical to physiotherapy, speech and language therapy to the psychosocial – and importantly, the blurred boundaries between neurology and psychiatry.

On a similar theme in her careful ethnography, Mattingly has described the two streams of language which health professionals use on a busy Stroke Rehabilitation Ward in the United States. She describes Chart Talk (a so called anti-narrative mode) juxtaposed with the Storytelling mode, in which the narratives of patients surface. In one sense, we hear: MMSE scores, R. sided homonymous hemianopias, Calcarine sulcus infarcts and Activities of Daily living. Facts and Lesions. Risk factors and numbers. Yet we also hear: worlds appearing foggy, tales of World War air pilots, an intimate exchange between speech therapist and patient, the rediscovery of the word tears – tears of sadness, of joy, of the meaning of tears and of the function of the word in conversation. Mattingly, who’s narrative phenomenological method focuses on ideas of hope, posits this as a form of ‘clinical storytelling’, in which these processes become a mechanism of moral reasoning and of Aristotelean practical rationality. How should we proceed with this patient? What is the outcome we hope for? What, above all, is the best good here?

And thus, despite the tour de force (as Foucault argues) of the clinical gaze being cast on focal lesions and pathology; there are truths also to be found in narratives. Knowing is not an objective reality but a subjective experience, an embodied experience as we navigate through the world. As Mattingly expresses, ‘it is through the stories that the philosophical – perhaps existential – questions are raised, questions about the human condition and the place of suffering and hope in it’. Perhaps in the telling of which, we allow the wings to take flight.

References

Desjarlais & Throop (2011) Phenomenological Approaches in Anthropology, Annu Rev Anthropology 40: 87-102

Mattingly (1998) In Search of the Goof: Narrative Reasoning in Clinical Practice, Med Anth Quaterly 12(3): 273-297

Mattingly (2010) ‘The Lobby’ in The Paradox of Hope: Journeys Through a Clinical Borderland, University of California Press: 7