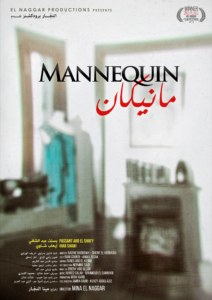

The Banality of Evil – Review of Mannequin, Egypt, 2015, directed by Dr Mina Elnaggar

Reviewed by Professor Robert Abrams, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York

Mannequin is a short, terrifying film with ambitions as large as its 7-minute running time is brief. The action starts immediately: An unnamed man who must have his wife’s dress retailored as a birthday gift has evidently placed an advert for a seamstress. When Mofida, the young woman who has responded to his advert, arrives at his home, he starts behaving oddly. The mood turns voyeuristic and sinister when he begins to make demands of her, including that she must wear and model the dress. The viewer now senses that Mofida might be used as an alter ego for the man’s wife, an inert substitute, as if she were indeed a lifeless mannequin. We watch with fascination and fear as an ordinary transaction changes over to the deceitful entrapment of an innocent woman.

Several questions are raised: What circumstances could justify the evil intentions this man appears to harbor? What internal conflict he is attempting to resolve?

The film can be viewed below.

Now that some details have been clarified, there is more to consider. We know that there are truths that are so unbearable that outright denial must be marshalled, and often that denial is framed in a uniquely personal way. This man’s wife has presumably been unfaithful, a circumstance he re-enacts by dousing Mofida with men’s cologne when she has put on the dress. Why someone who has been (or believes that he has been) betrayed by his wife chooses a particular style or format of disavowing is the province of psychoanalysis, not elucidated here.

But this is also where Mannequin reaches for a deeper understanding of the nature of vengeance. Although the implications are not immediately apparent, in only a few minutes it becomes clear that this film is depicting a perversion of anger and grief. The director, Mina Elnaggar, seems to grasp that narcissistic rage arises from a perceived threat to the narcissist’s self-worth. In the mainstream psychiatric view, a person with pathological narcissism might experience infidelity as a grave threat to his integrity, reacting with extreme anger or devaluation of the unfaithful partner as a way of avoiding emotional pain (Pincus AL, Lukowitsky MR. Pathological Narcissism and Narcissistic Personality Disorder. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. April 2010. 6:421-446). Here, in a variant of pathological narcissism, the cuckolded man further engages in a kind of “undoing”, a defensive revision of reality wherein it is no longer his wife who has wronged him, but a randomly found young woman; and while his victim might pay dearly for him being betrayed, the man seeks to avoid suffering himself. Also, in this delusional world, violence against others is acceptable if they are viewed as dehumanized mannequins; but if the mannequins resist, they just might have to be rendered lifeless again.

One of the defining characteristics of adulthood is the ability to distinguish between fantasy and reality. In essence, fantasy is the notion that one can control the world, with no restrictions placed on one’s libidinal urges, but this happens only in psychosis, pathological narcissism, sociopathy, or films.

In Mannequin, the protagonist is in a desperate flight from the immutable reality of whatever his wife has done that has been so damaging to his core identity. What the film does show, as a kind of reward to the viewers for tolerating the convoluted thoughts and images, is that unprocessed narcissistic rage is a zero-sum game, a desperate, losing position that can only enfeeble, rather than strengthen or vindicate the self. The elaborate avoidance of pain leads only to more pain for all concerned.

Mannequin provides a thought-provoking inquiry into a very dark domain. Its central character seizes control over the life of his victim as he cruelly manipulates her, but in fact it is he who is being controlled by unconscious motivations of which he is unlikely to be aware. From there, it is not a great leap to recognize that vengeance born of narcissistic injury can become murderous, but will still be impotent, whether on an individual or a global scale. If this man’s denial or undoing—call it what you will– had been satisfying, he would not need to repeat it, a point that is eerily hinted at in the film. Mannequin, despite its short span and familiar, ordinary setting, manages nothing less than to shock the viewer to a deeper appreciation of the underpinnings of human violence.

Address for correspondence: rabrams@med.cornell.edu

Interview with Dr Mina Elnaggar- actor, film director and producer

Can you introduce yourself to the readers?

I am a clinical nutrition specialist, but before that I used to work in the forensic department at MUST University. I worked in several theatre performances inside and outside of Egypt, such as ‘No time for art’ directed by Laila Soliman; in addition to the ‘Cairo trilogy’ with the BBC radio 3 directed by John Dryden; plus some interesting roles in TV and film in Egypt.

What was the reason behind your choice of a mentally-disturbed person as a main character and what were your cinematic influences?

I was always passionate about theatre and cinema since childhood, but I never studied either in an academic format. Most of my studies were independent self-driven attempts. I was fortunate to attend several theatre/ film workshops where I gathered loads of useful information. I am a big fan of Daoud Abdel Sayed (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Daoud_Abdel_Sayed). His 1991 film ‘Kit Kat’ (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Al-Kit_Kat) was one of the films that left a big impression on me as well as ‘The Land of Fear’ (http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0233234/plotsummary?ref_=tt_ov_pl). But my real influence was theatre. That was my real source of inspiration in making my own films. For example breaking the fourth wall was one of the tools I applied in ‘Mannequin’ to engage the viewers – whether to empathize with the victim or be a silent witness.

How did your film work support your interaction with patients?

Working with film and acting has several psychological aspects that runs fluidly back and forth; as an actor I have to dig deep and uncover my personal truths and convictions, and in doing that I was able to widen my perspective. In return, I was able to deal more flexibility with patients and understand their urges and needs. Honestly I believe that every person (doctor or otherwise) should have a go at acting because it makes you better understand yourself. Acting helps you to identify your own personal journeys in a civilized manner.

Films take you to different realities and help you plunge into different worlds. A film can also help release the pressure of everyday life stressors.

Which films do you encourage your students/ patients to watch and why?

I tell them to watch any types of films and not just art films; I also encourage them to go to performances, theatre, galleries, and any place that provides a form of art to exercise their creative muscles