Best Man by Owen Lewis. Dos Madres press, 2015

Reviewed by Wendy French.

Best Man has just been awarded first prize in the Jean Pedrick Chapbook prize from the New England Poetry Club. When you read the poems you can certainly understand why Lewis’s work has received this recognition.

Edward Hirsch’s epigraph features at the beginning of the collection and is entirely apt for all that follows:

Look closely and you will see

Almost everyone carrying bags

Of cement on their shoulders.

How universally true this is. Although our bags of cement may be entirely different from the ones that Lewis carries, they are nevertheless present. It is for this very reason that Best Man can speak to each and all its readers.

The poems focus on anger, regret, failure and love. They are about all that it is to be human, and specifically to love a brother in a hopeless situation.

In the collection, each of the poems stands alone, but together they tell a story of dependency, support, and of the fight against a battle with drugs and addiction. The story needed to be told. I read the book as a single unit from beginning to end, as the poems together record a young man’s life and were written from the standpoint of despair. Once I started reading, I felt compelled to finish. Lewis truly captures the pain and anger that he, an older brother, felt towards his sibling who was, as well as destroying his own life, destroying that of his parents, his grandmother, indeed his entire family. I was totally engrossed in the unfolding narrative and desperate to find out how it would all end. In each of the poems there is a level of intensity that drives the words forward and into the next poem.

The collection opens with Post-script, Unwritten Letter where Lewis looks back over childhood and the familiar games that children play:

‘… like the children we were

digging through the backyard soil, determined to get to China,

The spot under the swings

where our feet whisked the ground before each pendulum soar…’

These lines determine the relationship between two boys. The poem ends:

‘Wherever you’ve been you’ll have something to tell me. I expected

to know more.’

I had to re-read these lines as that situation, where we have lost friends and want to know more of their lives, is so familiar. Tragically for Lewis, the loss is that of his brother, whose full story will never be known. How did this fall into addiction begin?

This was a brave book to write and it took Lewis thirty years to be able to tackle the content. Lewis is not afraid to be truthful:

I am still mad at you.

Every week another call

from a burnt-out Bronx

neighbourhood, or Brooklyn…

…our grandmother told me you were ok.

She cooked you a pair of fried eggs.

The very fact of a grandmother feeding her grandson, hoping that this might bring him back to his senses, reveals a family pulling together and trying to overcome the situation. When you care for a loved one, you believe that food conquers distress. We all at times clutch at straws.

Lewis comes from a Jewish background and it is not until the fifth poem, Once, that we learn that his brother Jason had been adopted. Born to an Italian mother, Jason is brought into the Lewis household by Lewis’s grandmother.

…Once upon a time, it’s true,

the mother and brother, a pair,

looking out, a long wait

for the new baby to get there…

I’m your brother, and, so I’m…

Too long upon this time.

The poems are dark yet also uplifting because of their honesty. Lewis never tries to excuse his brother or to make excuses for himself in how he responds to addiction. This collection gives readers permission to confront their own demons and to write about them. No one is going to judge us or our reactions. Lewis has shown us how to do it. He has not abandoned his brother but is still talking to him after thirty years. Jason still has a prominent place in Lewis’s life and he listens to what his brother may be saying to him from beyond the grave. Lewis is working through his own feelings and is trying to make sense of his inexplicable loss. He never once blames his brother as an adopted force that came into the family, but fully accepts that Jason is his brother, and that he died at the age of twenty three.

The poems are beautifully constructed and restrained. They explore the chaos that addiction can bring to a family. Jason’s girlfriend, also hooked on heroine, is behind some of the late night frantic phone calls that Jason makes to Lewis. I have the feeling that Lewis helped to sort out the chaos that still existed in his mind about his brother’s death by writing this elegy. It seems that Lewis’s second marriage to Susan was the catalyst for this collection. He wanted to introduce Susan to Jason, and vice versa. In the poem Introducing, Lewis writes:

Under the chuppah

The rabbi will call: Yaacov ben Simcha…

You’ll ride on my shoulder –

Best man!

These poems are compassionate:

And what of the family’s soul,

Mother, as if you already knew

his disquieted soul won’t find peace…

ruthless:

Your breath is foul from rotten

meat. Your nostrils flare me

fresh in the cave of your furry hug.

nostalgic:

Remember how each year

we’d come back, have to learn

the beach all over again?

confused:

… you don’t know how

you passed a bill to the cashier

or how she passed you change

and why she is smiling or how

your hand cold lift the cup…

angry:

Okay brother,

Give me what you got.

A kick to the solar plexus.

full of searching:

This morning, the hour of haze,

a blackbird called through my window

with some urgency. (I think it was you.)

This fine collection would be very helpful for any family involved with a loved one going down the addiction route. The poems are energetic and the energy released will speak to many who are trying to understand this destructive path. The poems could act as a personal counsellor by offering the different stages of grief. Each reader can digest the content at his or her own individual pace.

The book would also be a useful teaching tool in the narrative medicine field as it demonstrates how personal stories paint a lucid and detailed understanding of the subject.

But first and foremost it is a book of poems that Owen Lewis has dedicated to his younger brother who died at the age of twenty three while hooked on drugs. The poems reflect a tragic story of a young life wasted.

Best Man should be widely read as these fine poems hit hard upon the dormant tragedy in all of us that perhaps looms around the corner. Lewis’s work depicts an unsettled world that is within each of us. From the outset, we realise that we are not in for an easy read.

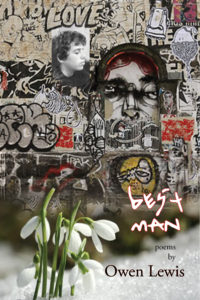

A finely produced book, Best Man has an arresting cover depicting youth, confusion, and the beauty of snowdrops that appear in a touching poem, Thaw.

I hope that for Owen Lewis the thaw has begun with the publication of this work.

Wendy French

Wendy French, Thinks Itself A Hawk, poems from UCH Macmillan Cancer Centre. Hippocrates press, 2016