Aliceheimer’s. Alzheimer’s Through the Looking Glass

By Dana Walrath. Published by The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2016.

Reviewed by Dr Martina Zimmermann.

Dana Walrath’s Aliceheimer’s. Alzheimer’s Through the Looking Glass is the second graphic memoir by an adult child about her mother’s Alzheimer’s disease, after Sarah Leavitt’s Tangle. A Story About Alzheimer’s, My Mother, and Me (2012); a further contribution to the steadily growing body of dementia caregiver life-writing. The best-known representative of this body is surely John Bayley’s Iris: A Memoir of Iris Murdoch (1998) – given the account’s prominent filmic adaptation, its unceasing consideration in literary scholarship, its persistent presence in the lecture theatre and seminar room, and the countless citations other caregivers take from this text. For these caregivers, Bayley’s narrative has provided inspiration, and at times moral justification – especially for how they tell about the patient’s loss of self. Walrath foregoes reference to the experiences of other caregivers. Instead, she connects her account to Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and Through the Looking Glass (1871). Allusion to Alice’s Adventures in caregiver narratives is not new: Cécile Huguenin made the connection in Alzheimer mon amour [Alzheimer my love] (2011) and Sally Magnusson in Where Memories Go. Why Dementia Changes Everything (2014). Both wife and daughter refer to being lost in an environment that resembles Carroll’s nonsense world, exposed to the nonsensical organisation of caregiving and lacking support from practicing clinicians. Walrath, however, maps her narrative onto Carroll’s story to depict the condition itself. In doing so, she offers an unexpected perspective on Alzheimer’s disease; she seemingly creates a new condition: Aliceheimer’s. Concurrently, Aliceheimer’s acknowledges that Alzheimer’s disease creates a new person, indelibly linked to the Alzheimer’s disease experience. Alice is no longer “her old self” – a “proud, hardworking career woman [who] had done all the cooking and cleaning for her family of five, without any outside help” (11). Having fallen down the rabbit hole, she now is “her new self” (27): Aliceheimer.

A pronounced feature of Alice’s dementia is disease-related hallucinations and fears, and Walrath dedicates a large part of her account to this aspect of her mother’s illness experience. This choice of presentation makes Walrath’s narrative unique. In fact, affective symptomatology, that is auditory hallucinations as well as ideas of jealousy, had been described by Alois Alzheimer in the landmark case of Auguste Deter in 1906. However, cognitive and histopathological features took priority in medico-scientific and healthcare descriptions of dementia patients in the first half of the twentieth century and beyond. And while the patient’s mind and psyche entered the literary arena much earlier and more explicitly (since the 1920s) as compared to when and how old-age psychiatrists and social medics began to take an interest in this area, they continue to remain absent from most caregiver accounts. Walrath describes some of her mother’s hallucinations, but more importantly, she gives them new meaning, depicting them as Alice’s space time travel and a special power (37). What happens under the spell of Alzheimer’s disease happens in wonderland. Mapping her mother’s experiences onto the adventures of Carroll’s character is a gambit that enables the caregiver to counter-narrate the patient’s social death and loss of self in a culture “where death is taboo, and aging is not celebrated” (47).

Walrath confirms what anthropologist Janelle Taylor explored in her prize-winning essay “On Recognition, Caring, and Dementia” (2008), namely that recognition is considered to be the “public threshold” (69). Specifically, the first thing Walrath is asked when her interlocutor learns that Alice has been placed in a nursing home is: “does she still recognize you?” (69) An anthropologist herself, Walrath asserts that “more than recognition of individuals and their social roles, it is recognition of intention and behavior that matters” (69). This insight is core to Walrath’s caregiving practice, as she assigns intention to Alice’s hallucination-caused behaviour – a strategy also pursued by Reeve Lindbergh in No More Words. A Journal of My Mother, Anne Morrow Lindbergh (2001). Lindbergh’s literary account of her mother’s dementia features among those we perceive of as particularly enabling because it seeks to identify the patient’s continued identity and self within dementia. Similarly, Walrath concedes that “there is loss with dementia, but what matters is how we approach our losses and our gains. Reframing dementia as a different way of being, as a window into another reality, lets people living in that state be our teachers – useful, true humans who contribute to our collective good, instead of scary zombies.” (4) This approach echoes that of other caregivers, like Arno Geiger in Der alte König in seinem Exil [The old king in his exile] (2011), Ruth Schäubli-Meyer in Alzheimer. Wie will ich noch leben – wie sterben [Alzheimer’s. How will I continue to live – how will I die?] (2010) or Cécile Huguenin, who depict their parent or partner as teachers. But in comparison to these caregivers Walrath does not give her mother her own narrative space. Aliceheimer’s remains Walrath’s account. And as such it reveals that a balance between continuity of identity for the patient as parent and continuity for the caregiver as child is not easily found – neither in the illness experience itself nor in an account thereof.

Walrath writes beautifully about how she creates continuity within and for her mother’s behaviour, how she discovers gain within loss. But we are only told about the “more benign hallucinations” (5) relating for example to the patient’s sundowning (35), not the difficult ones. We read about Alzheimer’s disease as “a time of healing and magic.” (4) But we are not told about the profound challenges of dementia caregiving. We gain such information only from the acknowledgements, where Walrath concedes that “[c]aring for Alice required a community […that] gave Alice space to be herself and to grow even through loss.” (71) Where are the caregiver burden and identity crisis of the child in this narrative? Are these challenges not explored in more detail, because we are expected to fill them in from our knowledge of the mainstream dementia narrative? I believe that the key to these questions is found in the narrative’s collage technique.

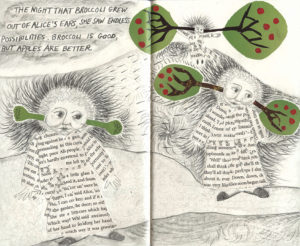

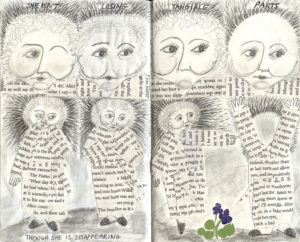

There is a clear compositional strategy in Aliceheimer’s: on the left the patchwork image of pages cut from Carroll’s text incorporated into Walrath’s own drawings and colouring; on the right Walrath’s written account in one-page long snippets and impressions. In a first instance, this arrangement gives the disease-inflicted, hallucination-provoked chaos a systematic structure. But more importantly, it enables Walrath to tell two different stories. The author encourages us to “[p]age through to feel the storyline as it exists in the drawings on their own” (5). But the collage depicts a truth on which the textual narrative – effectively like every Alzheimer’s disease memoir – remains silent: the patient’s complete disintegration and dissolution. The collage arrangement leaves space for the onlooker to imagine the full truth conveyed in Aliceheimer’s. In the end, Aliceheimer’s is Alzheimer’s: a disease of relentless loss and decline.

Roughly a third of the account covers the time from when Alice is placed in what Walrath terms “memory care”. From the time of Alice’s placement the pictorial narrative tells an explicit story of decline, regression and involution, of what Walrath only once spells out in writing, namely that “with each passing day, Alice was becoming developmentally younger” (61). The collage images show Alice as a young bride, a school girl, in her babyhood; Alice’s eventual bodily and mental disintegration become clear from images depicting Alice in the immediate post-fertilisation phase with the zygote (a spiral cut from a page of Carroll’s text) surrounded by sperm cells (64), and another image reducing Alice to mere DNA (the cut-out text from Carroll’s narrative that links the molecule’s two strands together featuring key characters in Alice’s adventures [66]). Instead of telling about Alice’s disintegration in the nursing home in her written account on the right, Walrath now takes to peering through the looking glass in yet another way. She sets out to explore Alice’s past and describes her personality in the past. With this account, she can place the “old” Alice before the increasingly disintegrating Aliceheimer. Not only do photographs of the young Alice begin to replace Walrath’s drawn image of her mother. In this final third, some chapters extend over more than one page, indicating that the caregiver needs to tell more of the story than the image alone can or should tell. Where the narrative snippet spreads onto the next page, the accompanying image is repeated in magnified form, suggesting that eventually the caregiver’s story must replace the patient’s world. Walrath, indeed, depicts her mother as increasingly transparent early on (10-15) and – like other caregivers such as Elena De Dionigi in Prima di volare via. Quello che l’Alzheimer non ci può rubare [Before flying away. What Alzheimer’s cannot steal from us] (2012) – as flying away (18-22).

Aliceheimer’s remains Walrath’s account also for the fact that it creates continuity for the daughter that reaches beyond her professional interests. In the first place, it tries to give meaning to the caregiving process, as the daughter now has to mother the mother, or as Walrath – mother of three boys herself – puts it: “I had always wanted a daughter” (57). Equally, Walrath describes the period of caregiving as a time when she “wanted to create a bond with my mother, to redo the past, and to fill the hole inside of me” (1). And as such, Aliceheimer’s also remains Walrath’s account when the narrative turns into the daughter’s search for the mother’s past as the story of her own origin; a past that will be forgotten with Alice’s memory loss; a past that harbours Alice’s as much as her daughter’s identity as Armenian. In this regard, Walrath’s narrative fits into the tradition of adult-child caregiver narratives that arose during the 1990s’ memory boom; narratives about a parent’s dementia whose forgetting becomes linked to the danger of an entire generation’s loss of collective memory about the trauma and fate of the Jewish people – if we think about Linda Grant’s Remind Me Who I Am, Again (1998) or Lisa Appignanesi’s Losing the Dead (1999). Like many caregivers before her Walrath becomes the “archivist”, not only of the mother’s memories, but an entire people’s history: she travels to Armenia to “make the missing pieces of our past into more than ideas” (61).

Peter Keating has described Carroll’s Alice as having “pioneered the new mood of freedom and exploratory play in children’s books”. Walrath’s narrative could be read as representing a new mood of freedom in how to deal with Alzheimer’s disease. It is a narrative about Alice’s different identities, views and truths of the world; a narrative showing that “[c]onflicting realities can coexist in a single image just as they do for people with dementia and their caregivers” (5). Walrath asserts that her mother “escapes the captivity of Alzheimer’s through story” (29). Also Walrath herself escapes the captivity of Alzheimer’s through story: the captivity of the medico-scientific and wider cultural narrative of decline, diminishment and loss. To my mind, Walrath’s reference to Carroll’s “Lobster Quadrille” (47) is most revealing. In this adventure, Carroll’s protagonist offers to tell her experiences on condition of not “going back to yesterday, because I was a different person then”. Living well with the patient comes down to living in the present moment – living within the world and experience of Aliceheimer. When this is not possible any longer, Walrath’s memory of her mother’s old self, Alice, will come to replace both Alice’s memory and Aliceheimer herself.

If this is the first Alzheimer’s disease narrative you pick up you will come away with the feeling of having read a kind of fairy story – about Alzheimer’s through the looking glass. If you read it against the last decade’s caregiver life-writing, you will see it fitting into how adult children increasingly assert their parent’s continued identity and self within dementia. Reading it in the context of nearly thirty years of Alzheimer’s disease life-writing, Aliceheimer’s appears original in its collage approach, and buoyant in its message of how to “bring back the humanity of a person with dementia” (5). But it also matches what has developed into a kind of prototype caregiver dementia narrative. It tells of biographical disruption; searches for continuity for both parent and child; aims at preserving collective memory; presents – as John Wiltshire has discussed in relation to John Bayley’s memoir – “the issues of identity which are implicit in all illness experience with particular acuteness”. Aliceheimer’s is a story about the possibility to find quality of life in dementia caregiving; the possibility to see Alzheimer’s disease as creating a new self, a self that can be lived with and written about up to the moment when we feel threatened in our own self.

The final review in this series – Alzheimer’s disease and graphic memoirs – will be Sarah Leavitt’s Tangles.

The first in the series – Alex Demetris’s Dad’s Not There Anymore – was posted here.

Related Reading

, Yugin Teo. Carers’ responses to shifting identity in dementia in Iris and Away From Her: cultivating stability or embracing change? Med Humanities 2015;41:2 81–85.

Martina Zimmermann. Deliver us from evil: carer burden in Alzheimer’s disease. Med Humanities 2010;36:2 101–107.