‘His Masters Voice’. Painting by Francis Barraud, 1919. Credit:Courtesy of the EMI Group Archive Trust

THIS IS A VOICE

Wellcome Collection, 14 April – 31 July 2016

Reviewed by Steven Kenny

Approaching the exhibition entrance of THIS IS A VOICE at the Wellcome Collection, it is easy to think the voice is treated as criminal, being contained, controlled and its behaviour segregated from the world outside. Initial thoughts would suggest that it is being acoustically surveyed; with the steady opening and closing of the exhibition door, sound rushes to the exit. Yet its attempts are ultimately futile, the room has been sound proofed, noise restricted from accessing the outside world. On entering the space, grey triangular padded shapes line the walls, detail reminiscent of a kitsch science fiction film from the 1980s. The exposed patterned structures, evocative of the décor of Ridley Scott’s periled spaceship in Alien, enclose you in a warm, familiar hug of nostalgia. Sensing that this space is one visually tread before, it is easy to forget the prestigious institutional context of the exhibition. THIS IS A VOICE, a show investigating the potential of the voice in all its forms, techniques, objects and cultural baggage, is particularly engaging for it knowingly understands such a topic cannot be wholly represented (due to various cultural and language complexities). Yet it does a heartfelt job in attempting to at least understand how the voice as a product, both commercially and non-commercially viable, can be exhibited. Curatorial flourishes can be found everywhere, from the nooks and crannies of seated listening stations to the maze-like paths that allow a gentle flow of avid listeners from one space to the next. From attending numerous shows at the Wellcome Collection I must comment that THIS IS A VOICE is one of the most stimulating and generally refreshing exhibitions to be held in its space.

It would seem that an inner versus outer exploration of the body and the voice is focused on throughout. One telling example of this is immediately apparent in the work Circular Song, 1974 by Joan La Barbara. A half dome like structure hangs from the ceiling, the speaker’s hollow interior pervading the space below with sound. The experience of entering this wall of sound is generally unnerving, a constant and increasingly uncomfortable echo of inhaling and exhaling performed by the artist, breathes all over you. It is nightmarish, a deathly noise that would seem totally apt in the exhaling howls of a victim being chased by a stalker in a nerve inducing slasher film. Sound in this manner is represented as an abject substance, an uncanny emotional pulling of the visitors’ own sentiments to the body and the amplified vocalisation of a body process that now seems one of disgust. Yet this is in direct contrast to Marcus Coates multi-screen film installation Dawn Chorus, 2007, which is silly, funny and surprisingly touching. This room is filled with the fluttering sounds of birdsong, a number of monitors positioned at varying heights depicting subjects in everyday locations comically singing along to each sound created. Experiencing this work initially seemed deceptive–I could not understand how both image and sound aligned so perfectly, as though the birdsong was actually being produced by a human lip whistle. Subjects pursed their lips and jotted their heads up and down in perfect alignment. The façade is lifted on reading the work’s description: ‘After recording the dawn chorus with multiple microphones, the individual birdsongs were slowed down to last approximately 16 times as long, which enabled the participants to imitate them, while being filmed’. Yet not knowing these details did not matter as my imagination roamed freely around the space. I observed each subject as one would watch a bird in the wild, mesmerised by its harmonic whistle and merry bouncing of its head.

THIS IS A VOICE at Wellcome Collection, 2016. Credit:Photography by Michael Bowles

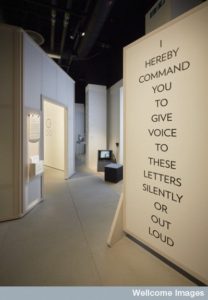

Dotted around the exhibition are various textual works, the written word laid bare. Erik Bunger’s wall text I Hearby Command You to Give Voice to These Letters Silently or Out Loud, 2011 was surprising in that it forced an involuntary restriction of my own voice from permeating the gallery. I so badly wanted to shout out loud the words I was reading yet thought better than to add to the already noisy space. Yet on second thoughts maybe that would have made for some interesting spectator reactions. Bunger’s playful register, was paralleled by Mikhail Karikis’s digital prints (photographs by Thierry Bal) Sculpting Voice, 2010, where the artist was photographically recorded pulling various facial gestures. Three prints line the wall in sequence, each exhibiting Karikis’s comically retuned face, made even more comical by the muting of what would probably have been quite a painful or otherwise loud projection of sound.

The exhibition saved its loudest and most intriguing work for last. Entering the final room of the show, you would think that you might have woken in a Lynchian nightmare. Best described as an interactive, participatory constructed, sound installation, a lone and somewhat foredooming sound booth, tempts the spectator.

The aptly titled Chorus, 2016 is by the British electronic musician Matthew Herbert, whose work ‘asks visitors to sing a single note within a professional recording booth following a set of instructions. The visitor’s voices are then automatically added to a chorus of voices, including performers and staff from the Royal Opera House, forming an ever-expanding sound installation that plays in the exhibition space and at the Royal Opera House’s Stage Door in Covent Garden’. I entered the space to sing the requested solitary note. Escaping my throat, my voice joined the squeaks, squeals, and sometimes correctly pitched notes above. Noise reverberated violently throughout the room, puncturing the space like a diminished fifth encroaching a melodic passage. The voice in this exhibition is presented as an ever-changing entity, one that is able to attack, calm and arrest.

Articles from Medical Humanities on the human voice:

Kelly BD. Searching for the patient’s voice in the Irish asylums. Med Humanit 2016;42:87-91.

Demjén Z and Semino E. Henry’s voices: the representation of auditory verbal hallucinations in an autobiographical narrative. Med Humanities 2015;41:1 57–62.

Puustinen R. Voices to be heard—the many positions of a physician in Anton Chekhov’s short story, A Case History. Med Humanities 2000;26:1 37–42.