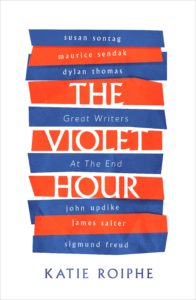

Katie Roiphe. The Violet Hour: Great Writers at the End. Virago, 2016

Reviewed by Professor Robert C Abrams, Professor of Psychiatry, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York

A central premise of Katie Roiphe’s The Violet Hour is that the awareness of approaching death is a milestone we all will face at some time and in some form. From there, Roiphe explores how the moment of awareness, the awful prognosis, was confronted by each member of an august selection of writers and thinkers. But it is not only that first acute glimmer of understanding that Roiphe examines, since dealing with death more often than not involves a lengthy, even a lifelong, prodrome, an unwelcome perception that appears slowly and gathers to invade consciousness.

Roiphe’s subjects are persons of uniquely substantial depth, creative visionaries in their own fields—Susan Sontag, Sigmund Freud, John Updike, Dylan Thomas, Maurice Sendak. An interesting aspect of the book is that, when the subject is death, these luminaries are just as avoidant and vexing as the rest of us. One is at first tempted, naively, to believe that what these individuals have accomplished in their lives ought to ease the pain of anticipated death, or enable them to articulate the experience in a way that leads us to greater insight. However, intellectual or artistic stature does little to soften the impact or illuminate the journey—at least for this select group. Instead, Roiphe shows how the nearness of death strikes with terror at one’s narcissistic heart and can derail the psychological homeostasis of almost everyone.

What can be derived from the accounts of these great thinkers is therefore not clarity, but an analysis of how they actually felt as death loomed. In a way, Roiphe’s writers coped with death much as they had lived, in all their contradictory ways. Like strands of spaghetti Bolognese, each story line branches out and swirls around in so many messy directions that the themes can be difficult to untangle and trace. (In fact, compared with their highly variable, tortured pre-death processes, the actual moment of death for these writers seems to have been uniformly anticlimactic; all the complicated action has taken place earlier). So it is that we are shown how Dylan Thomas dreaded death but died in a self-destructive orgy of alcohol and Benzedrine, the culmination of years of punishing abuse of his health. John Updike, on hearing his dire prognosis, turned immediately to poetry, for him a reliable source of consolation, and he kept at it, creating what some have considered his finest work, for as long as his strength allowed. Susan Sontag did something similar, finding solace under the cover of the intellectual constructs that were her hallmark, except that she fiercely refused to give in or let go; she marshalled all the intellectual force at her command to master her illness and survive it, until she simply fell away. Freud was magnificently inconsistent: Freud, the ultra-rational doctor who once famously insisted that “a cigar is just a cigar” could never give up what he knew was rooted in primitive oral gratification and thus knowingly died of smoking-related cancer. Maurice Sendak, who seemed to have imbibed angst prenatally, was completely preoccupied with death and had been preparing for it nearly all of his life.

But thinking about death when it is not proximal is very different from grappling with it in the moment. Death is something for other people, never for oneself, until it isn’t. But up to that moment, it is safe enough to wish for death, romanticize it, flirt with it. When death actually does arrive, it is presented as a full-stop but not necessarily a resolution; one dies, not after living but during it, leaving everything that is unsolved, unsolved. Again, these observations would be unremarkable were it not for Roiphe’s notion that the deaths of such hyper-articulate individuals should be exceptionally revelatory. That in the end her characters are merely ordinary humans contending with the direst possible threat to their existence may be in fact the point.

If The Violet Hour can be a dark, depressing read, it is also a brilliant one, framed in stunning, exquisite prose by an artist-of-a-writer. Roiphe’s introductory synthesis of thoughts about death could easily stand alone as a splendid thought-piece, and there is a touching personal epilogue at the end. But for most of the book the author is rather coy about her own views of death. For that one must look to her casting choices. Starting with a set of 20th century cultural icons who wrestled with the concept of death and left written records and accounts of witnesses to prove it, her chosen characters add up to a grim group of players, John Updike being the sole possible exception. The others are grim, not only because they are dying, but because of the bleakness they have created for themselves.

It is probably a consequence of Roiphe’s selection of characters that there is missing in this book any serious discussion of hope—Emily Dickinson’s resilient little creature with “feathers.” Hope is too effeminate for the likes of Susan Sontag, who preferred to submit to a brutal stem-cell transplant in lieu of gentle palliation because the transplant offered a slim hope of survival. Hope is too shallow and totemic for Freud, who prided himself on tolerating pain with what Roiphe aptly calls “heroic clarity” instead of mind-numbing analgesics. Hope was off the radar entirely for that 20th-century poet-maudit, the personification of romantic self-loathing, Dylan Thomas. But for us ordinary folk, readers who are death-fearing, moderately self-defeating but not quite blatantly self-destructive, some consideration of hope just might be welcome.

In an influential article in the geriatric psychiatry literature, Sullivan succinctly formulated how “hopelessness at the end of life is not simply the absence of hope but attachment to a form of hope that is lost.” [1] Consistent with the writings of Erik Erikson, [2] this view holds that a dying person must deflect mental energy away from the goal of survival, the currency of which has been divested of all value, to some alternative ethos consistent with his life and personality; this should ideally be something larger in scope than one person’s life, some experience or value that will outlast and transcend the individual, such as intimacy, democracy, art, or salvation. In the absence of any realistic point of future reference, redirection of hope becomes the urgent task to be confronted when one is handed a final sentence of death.

Considering Roiphe’s cases from this perspective, she shows how Sontag haughtily spurned everything but survival, and by embracing a losing cause, died sadly, though she left a spectacular record of written reflections. She documents how Freud, who worked until the end, died with little psychological adjustment to make, well aware that he had created an incomparably rich legacy; he also had an heir to his intellectual estate, his daughter, Anna, who was eager to perpetuate it. Only Updike seemed to achieve a meaningful transition; his hopeless prognosis spurred him on to new creative heights and enabled him to return, albeit briefly, to the top of his form as a writer, a peak from which prior to his cancer diagnosis he’d felt he had been slipping. Previously it had been sexual affairs that had seemed to energize his writing; now it was the awareness of death. When he could no longer write, he died. Neither Dylan Thomas nor Maurice Sendak ever entertained any sustained vision of themselves as surviving, so no such transition applied to them.

Reflecting on the absence of hope in the main body of The Violet Hour should not be taken as a criticism, for Roiphe, by clinging to neutrality and avoiding any position other than that of reporter until the book’s final pages, invites readers to abstract their own lessons from these stories and integrate them in a personal way. And it is fortunate indeed that she does not entirely neglect the critical human need for love, solace and inspiration at the end of life. It had to have been for such a purpose that she cited these beautiful lines written by the terminally ill John Updike:

“To live is good / but not to live—to be pulled down / with scarce a ripping sound, / still flourishing, still / stretching toward the sun– / is good also.”

References

- Sullivan MD. Hope and hopelessness at the end of life. Am J Ger Psychiatry. 2003; 11(4):393-405.

- Erikson EH, Erikson J, Kivnick HQ. Vital involvement in old age. New York: W.W. Norton & Company; 1994.