This is the first in a series of three books from the Costa Book Award 2014 category shortlist that will feature in the Reading Room. Elizabeth is Missing was yesterday announced as the First Novel category winner.

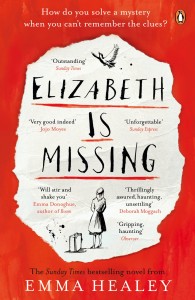

Elizabeth is Missing by Emma Healey

Reviewed by Andrea Capstick, Division of Dementia Studies, University of Bradford

One of the four shortlisted nominations for the 2014 Costa First Novel award, Elizabeth is Missing is an admirable attempt to place an older woman with dementia at the centre of a novel which otherwise belongs to the genre of crime or psychological thriller. The narrative unfolds on two levels. The back-story is a genuinely intriguing disappearing person mystery set during World War II when the central character, Maud, whilst still a child herself, lost her recently married sister, Sukey. The period detail here is well handled, particularly in relation to the social aftermath of war, and has clearly involved a lot of careful research. In the present day strand of the novel, the story of Sukey’s disappearance is paralleled by another vanishing, this time that of Maud’s long-standing friend, Elizabeth.

A central trope of the novel is that, due to her dementia, Maud perpetually confuses these past and present disappearances. Her problems with short-term memory lead her to go over the same ground repeatedly in her investigation of Elizabeth’s disappearance, whilst not being able to remember that she is doing so. In her pursuit of the truth about what happened to Elizabeth, Maud constantly writes notes to herself to remind her that ‘Elizabeth is missing’ and to suggest lines of inquiry that she needs to follow up on. At the same time, Maud confuses events relating to her sister Sukey’s disappearance with those of Elizabeth’s more recent unaccountable (to Maud) absence. Ultimately, we are made to realise that Maud does, in fact, remember historical facts that other people without dementia are not aware of, and that somewhere within the recesses of her memory lie the solution to a decades-old crime. Maud struggles to be heard and believed, and her determination to solve this double-faceted mystery is both moving and believable.

What worked less well for me was the credibility of Maud’s narrative voice. A certain amount of suspension of disbelief is necessary in our response to all fiction. In conventional third-person, ‘omniscient’ narrative, we quickly learn to ‘read through’ the narrative voice, accepting that we are being told what happened by someone with privileged knowledge. First-person narrative has always been recognised in literary theory as a more difficult form, particularly when we are faced with the possibility of an unreliable narrator. In the case of Maud’s present day narrative, the necessary suspension of disbelief becomes very difficult indeed. Here is someone who cannot remember what has just happened, even a couple of minutes earlier, who writes herself notes which she then immediately forgets about but who is somehow speaking to us as the first person narrator of the present day strand of the novel. How has this first-person, continuous present tense narrative got onto paper at all? This may not interfere with credibility for all readers, but it did for me, as I found I was constantly distracted by wondering about the impossibility of the story I was reading having been recorded. The attempt to represent Maud’s minute-by-minute subjective experience was a brave one, but felt as though it needed some additional narrative device in order to be credible, such as Maud having made audio-recordings that were then transcribed by a third party. Alternatively, given the relatively well-preserved recall most people with dementia have for remote events, it may have worked better had Maud’s first-person narrative related to the historical mystery, rather than to her halting present day attempts to find Elizabeth.

There is a very skilful interweaving of recurring themes and motifs in this book; lipstick, marrows, tinned peaches and particular wartime melodies crop up over and over again, at times almost turning the repetition often considered a ‘symptom’ of dementia, into something like an art form. There are also some extremely penetrating individual insights into how it might feel to have dementia; to have one’s underlying intelligence still intact but struggle to communicate with a dismissive external world. ’’They want you to have the right props” Maud says, ironically, “so they can tell you apart from people who have the decency to be under seventy. False teeth, hearing aid, glasses, I’ve been given them all.” The book is not written for laughs, but I did laugh in places at lines of Maud’s, such as “The word ‘plaque’ makes me angry”. Unfortunately this isn’t entirely consistent, and some sections of the book read rather too much like a creative writing exercise. Soil is described, for example, as being “chewable” but also as “spitting things out” within the same sentence, and the likelihood of Maud spontaneously using terms like ‘lasagne’ and ‘wok’ also seemed rather remote, given her other difficulties with word finding.

The novel is certainly unusual, and commendable, I think, in trying to combine a traditional murder mystery with a voyage into the subjective world of a woman with dementia. Ultimately, for me, it did not quite work on either level. The solution to the historical mystery would not have stood alone as a whodunit, because we suspect the answer from quite early in the novel, and it doesn’t help that the perpetrator turns out to be the most sympathetic character in the novel. The ending also somewhat undermines the strong theme running throughout the rest of the storyline about the potential for people with dementia still to be experts on their own experience, and to have strong convictions and loyalties. Nevertheless, there is a lot to learn from here. The book is dedicated to Healey’s grandmother and is no doubt based on observed real-life experience, which runs extremely true in some excellent set pieces such as the Mini-Mental State Examination test Maud has to endure on pages 154-157. Clinicians take heed and beware!

Elizabeth is Missing by Emma Healey.

Published by Penguin, 2015.