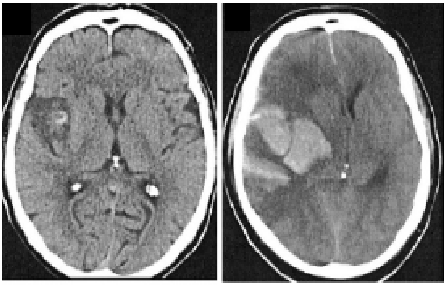

‘Time is brain’ is an increasingly iterated mantra in stroke care, underlying the push for swifter treatment for one of the leading causes morbidity and mortality in the world. The use of intravenous tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) has undeniably remodelled expectations of stroke care, and the recent introduction of the First Mobile Stroke Unit in Victoria is testament to such evolving change. In ongoing pursuit for treatment within the “golden hour”, the risks and complications of tPA, particularly symptomatic intracranial haemorrhage (sICH), must be equally as recognised (Figure: Intracranial haemorrhage following thrombolysis Derex et al, JNNP 2008; 79:1093-1099).

In the paper by James et al published in the latest edition of JNNP, the authors retrospectively determine the red-flag clinical features that herald sICH development from a cohort of 511 patients who received tPA for ischaemic stroke. 108 of this cohort experienced an early neurological deterioration (i.e during or within 24 hours of tPA). For 17%, this was attributed to sICH, mostly occurring after tPA with only 1 case having occurred during infusion. Patients with sICH were older, had a higher admission median NIHSS score, and a higher 24-hour median NIHSS score compared to those who had deteriorated without ICH. Interestingly however, the only independent predictor of sICH was the change in level of consciousness, with decreased responsiveness noted to occur in almost 80% of the ICH group.

The significant morbidity and mortality associated with tPA-related sICH has been a major barrier to the generalisation of thrombolytic therapy in the past, and has contributed to the therapeutic nihilism surrounding its use in clinical practice. The phenomenon itself is clinically complex and heterogenous, and a multitude of possible predictors have been previously identified in the literature, including high blood pressure, hyperglycaemia, age and baseline NIHSS score. Interestingly, only the latter two factors were associated with sICH in the present study, but even so were not seen to be independent risk factors on multivariate analysis. Headache/nausea/vomiting and the presence of concomitant anticoagulant/antiplatelet use on admission were also not associated with an increased risk of sICH, despite a clinical perception of being linked to this malign outcome.

Reiterating the ‘time is brain’ philosophy, early preparation of tPA reversal agents in such identified patients, prior to acquisition of brain imaging, may be the next step in post-stroke care pathways. Although the study findings need to be separately demonstrated across centres and in larger groups for generalisability, the need to reconfirm prior conceptions is evident. As such, this study foreshadows issues that will, undoubtedly, become increasingly applicable in acute stroke care models and clinical practice.