As trainees progress through their career, they are encouraged or even expected to train and supervise junior colleagues. Traditionally, this has been reserved for inpatient management, basic procedures such as vascular access, and more advanced procedures such as chest drains or central venous access. Whilst surgical training in the UK often pair a junior and senior trainee oncall or in the operating theatre, this type of training has not yet reached the endoscopy department. Despite this, once a senior trainee becomes a consultant, they are expected to train junior colleagues in endoscopy without prior exposure to training others in endoscopy. Although the Joint Advisory Group in Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (JAG) offer train the trainer courses, they are often costly as highlighted by Kumar et al.1 and cannot accommodate all new consultants on a yearly basis. In a recent interesting publication in Frontline Gastroenterology, one group from the USA examined the impact of having a senior gastroenterology trainee as a primary trainer for a junior trainee in endoscopy under the supervision of a consultant whose role was to ensure safe and effective procedure completion.2

In their qualitative study, which included direct observations of this training model and separate interviews of junior trainees, senior trainees, and consultants, the authors identified four key themes. Firstly, junior trainees found the near-peer teaching less intimidating and judgemental, and was accompanied with more relatable instructions from senior trainees compared to consultants. Secondly, senior trainees found that teaching was helpful for their own endoscopy skill development helping them to be consciously competent rather than slowly evolving to an unconsciously competent practice. Thirdly, junior trainees found it helpful when both senior trainees and consultants provided complementary teaching. Fourthly, there were instances where the consultants were training the senior trainee providing a learning opportunity for them and the discussion between the two more senior clinicians were helpful for the junior trainee. There were some challenges to this training model. A minority of consultants believed that it would be more beneficial for a junior trainee to learn from more experienced trainers and increased procedural time was often noted. In some situations, the roles and expectations of the three clinicians were not laid out at the start making it challenging especially for therapeutic procedures. Finally, some consultants felt that their attention was split between supervising the junior and senior trainee.

Given my interest in endoscopy and teaching, I found this study particularly important. I have been in a similar training situation and felt that it worked very well especially because the consultant laid out clear expectations at the outset for both junior and senior trainees. As a trainee approaching towards the end of my training, I believe this training model would have been advantageous to me both as a junior and a senior trainee. It is evident that this training model provides more training lists for junior trainees which is important given that trainees in the UK now spend only four, rather than five, years in higher specialty training.3 The benefits for the senior trainee should not be underestimated. Teaching others promotes deeper learning for senior trainees through effortful retrieval of skills and knowledge acquired during their own training. In addition, it also allows senior trainees to train colleagues in a supervised environment rather than being left to do it for the first time as a new consultant.

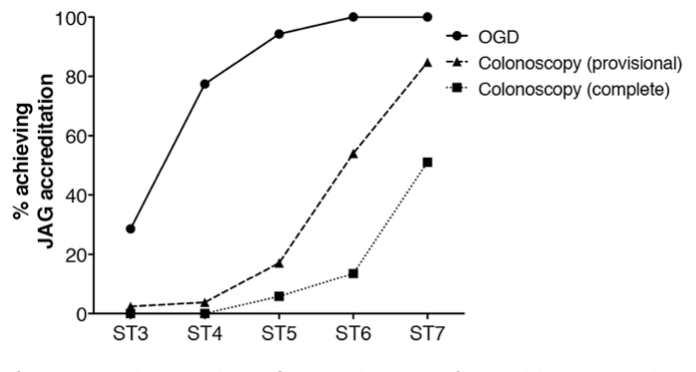

There are challenges to implementing this training model in the UK. Speaking with some trainees at the recent Digestive Disease Week conference, gastroenterology trainees in the USA anecdotally perform on average more than 500 colonoscopies by end of their training. A survey by the British Society of Gastroenterology demonstrated that only half of the trainees in the UK achieve full colonoscopy signoff, that is around 300 colonoscopies, by the end of five years of training (Figure 1).4 It would, therefore, be unrealistic for senior trainees who might not be fully competent themselves in diagnostic endoscopy to supervise junior trainees. On the other hand, slow implementation of such a training model may, as previously discussed, provide more training opportunities for junior trainees and accelerate their endoscopy training, meaning by the time they become senior trainees they will have performed more procedures. Given the substantial reduction in time allocated for gastroenterology training and the increasing demand for service provision in general internal medicine, novel strategies, such as this training model, are required to improve training quality and opportunities in endoscopy. Whilst developing these, it is fundamental to keep patients’ interests at the forefront, thereby fostering a healthcare system capable of training the next generation of endoscopists safely and innovatively. Future studies should, therefore, focus on whether this training model is feasible in the UK.

Figure 1. Proportion of trainees who achieved JAG accreditation for OGD and colonoscopy at each stage of training.4 JAG, Joint Advisory Group in Gastrointestinal Endoscopy; OGD, oesophagogastroduodenoscopy.

Author: Vivek C. Goodoory (Trainee Associate Editor)

Twitter: @VivekGoodoory

Declarations: I am a Frontline Gastroenterology Trainee Editor

REFERENCES

1. Kumar A, Wilmshurst S, Murugananthan A. JAG endoscopy training courses: are they financially sustainable? Frontline Gastroenterology. 2023;14(5):428-31.

2. Feuille C, Sewell JL. Senior trainee as endoscopy teacher: impact on trainee learning and attending experience. Frontline Gastroenterology. 2023. doi: 10.1136/flgastro-2023-102410.

3. Shape of Training. Securing the future of excellent patient care. General Medical Council (GMC) [Internet]. [London]: GMC; 2013 [cited 2023 September 1]. 2013;Available from: https://www.gmc-uk.org/education/standards-guidance-and-curricula/guidance/shape-of-training-review.

4. Clough J, FitzPatrick M, Harvey P, Morris L. Shape of Training Review: an impact assessment for UK gastroenterology trainees. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2019;10(4):356-63.