Although we live in an era of global collaboration, there are a number of circumstances in which gastroenterology practice in the UK is at odds with our European and Australian counterparts. For most UK gastroenterologists, for example, performing and interpreting ultrasound (US) in the outpatient clinic would be out of our comfort zone.

Two recent articles in Frontline Gastroenterology highlight the potential advantages in the rollout of this technique in the UK for the assessment of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).1,2 Whilst small bowel MRI is sensitive and specific for diagnosis and evaluation of Crohn’s disease, it is an expensive service to provide, with patchy provision outside of major UK IBD centres. Important, too, is the fact that many patients find the large volume of oral prep difficult to tolerate and disruptive to day-to-day life. Whilst most would accept this as par for the course in disease monitoring, I recall one patient saying the prep was worse than a typical disease flare!

There is evidence that, with the right expertise, intestinal ultrasound (IUS) has comparable sensitivity for detecting inflammation and strictures as MRI,3 and as such is a reliable non-invasive tool for assessing response to therapy and post-surgical recurrence. A key benefit would also be the ability to perform real-time assessment of disease activity in the outpatient clinic – not only does this save a second appointment, but equips both patient and clinician to ‘see’ the disease and discuss any change in treatment plan there and then.

Whilst the benefits of an IUS service are clear, the delivery is less so. Who should be performing these scans? If delivered by a trained gastroenterologist, this enables targeted review of suspected problem areas, such as a Crohn’s-related stricture, and enables immediate discussion of the next steps in management. But is this a good use of an ‘expensive’ clinician’s time? Can we expect a radiologist, although expert in US technique, to be familiar with disease process and able to address the targeted questions we seek to answer? A recently published International Bowel Ultrasound Segmental Activity Score has been shown to provide consistent and reproducible results when reporting disease activity, using parameters including bowel wall thickness, hyperaemia, and inflammation of mesenteric fat.4

Another consideration, of course, is whether intestinal ultrasound becomes another skill on a long list to shoehorn into a packed gastroenterology curriculum. With evidence that trainees already struggle to achieve key competencies,5 it seems likely that training in IUS is destined to become a post-CCT skill, or one requiring time out of training to acquire. Whatever the difficulties in ironing out the details of service provision, access to IUS has the capacity to improve the patient experience, reducing hospital visits and enabling timely escalation in treatment when required.

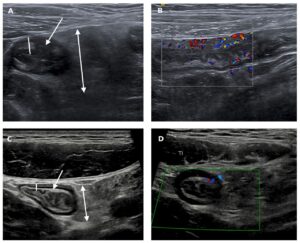

Figure 1: (From Shivaji UN et al. 2021) Selected intestinal ultrasound images from a young adult prior to (A and B) and at follow-up (C and D) after anti-TNF treatment. The pretreatment images show significant thickening of the terminal ileal wall (line in A), patchy mixed echo change within the submucosa of the bowel wall (arrow in A) and marked mesenteric expansion with oedema (double-headed arrow in A). There is considerable hypervascularity on the Doppler image (B). Following treatment, the bowel wall has returned to normal thickness (line in C) and normal mural architecture has been restored, with clear delineation of the outer echo-dark muscularis propria, the relatively echo-bright submucosa and the inner echo-dark deep mucosa (arrow in C). The deep mucosa (innermost echo-dark layer) is now of normal thickness (<1 mm). There is only mild residual mesenteric expansion (double-headed arrow in C). The Doppler signal is now normal (D). TI, terminal ileum, TNF, tumour necrosis factor.

References:

- Shivaji UN, Segal JP, Plumb AA, Quraishi MN, Ghosh S, Iacucci M. Intestinal ultrasonography: a useful skill for efficient, non-invasive monitoring of patients with IBD using a clinic-based point-of-care approach. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2021;0:flgastro-2021-101852. doi:10.1136/FLGASTRO-2021-101852

- Radford SJ, Clarke C, Shinkins B, Leighton P, Taylor S, Moran G. Clinical utility of small bowel ultrasound assessment of Crohn’s disease in adults: a systematic scoping review. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2021;0:flgastro-2021-101897. doi:10.1136/FLGASTRO-2021-101897

- Calabrese E, Maaser C, Zorzi F, et al. Bowel Ultrasonography in the Management of Crohn’s Disease. A Review with Recommendations of an International Panel of Experts. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22(5):1168-1183. doi:10.1097/MIB.0000000000000706

- Novak KL, Nylund K, Maaser C, et al. Expert Consensus on Optimal Acquisition and Development of the International Bowel Ultrasound Segmental Activity Score [IBUS-SAS]: A Reliability and Inter-rater Variability Study on Intestinal Ultrasonography in Crohn’s Disease. J Crohn’s Colitis. 2021;15(4):609-616. doi:10.1093/ECCO-JCC/JJAA216

- Clough J, Fitzpatrick M, Harvey P, Morris L. Shape of training review: an impact assessment for UK gastroenterology trainees. Gastroenterology. 2019;0:1-8. doi:10.1136/flgastro-2018-101168