By Tyne Baynton Cairns (They/Them) & Julia Bailey (She/They)

Contraceptive care guidelines are usually designed for cisgender, heterosexual women. In the heavily gendered context of contraceptive care, gender dysphoria is common among trans, non-binary and gender-diverse people. In healthcare settings, gender dysphoria can be brought on by the environment, the behaviours of providers, and the contraceptive methods themselves.

Gender dysphoria is the distress experienced from a societal misperception of a person’s gender identity (often described as an incongruence between sex assigned at birth and gender identity).

In contrast, Gender Euphoria is the joy experienced when one’s gender identity aligns with gender expression, and is affirmed by others. It has been suggested that gender euphoria could be a valuable framing of gender diversity in healthcare.

We interviewed seven gender-diverse people in British Columbia, Canada, who were assigned female at birth to explore their views and experiences of contraception and healthcare. Participants were encouraged to outline what they considered to be contraception. Participants intentionally included dental dams and gloves as contraceptive methods, knowing they do not prevent pregnancy. The inclusion of gloves and dental dams was due to their protection against sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and sentiments that they center queer pleasure.

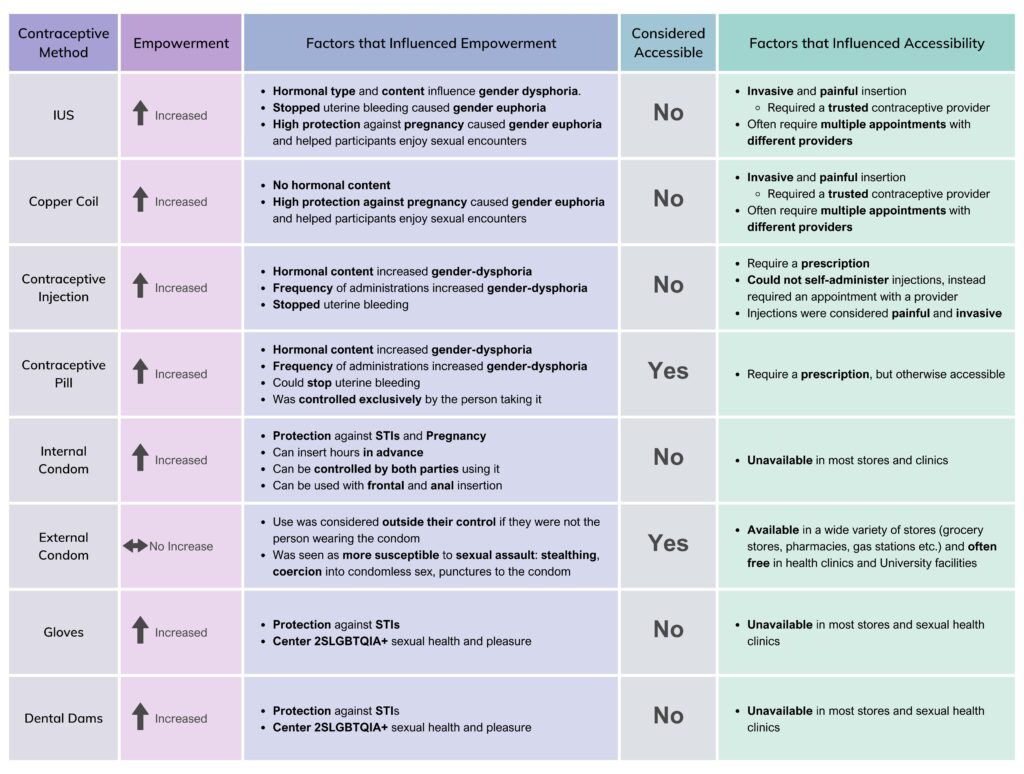

Copper Coils and Intrauterine systems (IUSs, also called intrauterine devices (IUDs) globally) were less accessible due to insertion procedures, which were described as invasive and painful. Internal Condoms, Gloves and Dental Dams were considered the least accessible by participants, as they were not often available in stores or clinics in Canada. The Contraceptive Injection and Contraceptive Pill required prescription appointments with physicians but were otherwise considered accessible. External Condoms were the most accessible contraceptive method, as they were available in stores and freely available in clinics and universities.

Participants used contraception to increase their bodily autonomy through empowerment in achieving a contraception-related goal (i.e., pregnancy/STI prevention, gender affirmation) without sacrificing psychological or social safety.

“I learned you can insert [internal condoms several] hours before you use them, and, like, they’re perfectly effective and, like, that is amazing […] all this agency was put into the hands of somebody who has – like, who has a vagina, to do what they want to protect themselves […] I’m really scared of stealthing*, like, I’m super like – cause like, it-it freaks me out that someone can just like betray you like that so. I like the idea of having a lot more control over that.”

Different contraceptive methods carried varying levels of empowerment (see Figure 1). IUSs, copper coils, internal condoms, gloves and dental dams were associated with increased bodily autonomy. The contraceptive injection and contraceptive pill empowered those wanting to prevent pregnancy, but caused gender dysphoria in others due to their frequency of administration and hormonal content. External condoms did not increase participant empowerment; external condom usage was considered outside of participants’ control if they were not the person wearing the condom. Fears of stealthing, and coercion into condomless sex, and other forms of sexual assault were serious concerns. Participants described an increased likelihood of coercion into condomless sex if they used an additional contraceptive method.

Figure 1. Empowerment and Accessibility of Contraceptive Methods

3. Access to Healthcare: Geographic and Financial Barriers

Primary care is responsible for most contraceptive prescriptions in Canada, complicated by a national shortage of primary care providers. Participants either did not have a primary care provider or travelled long distances (up to 6 hours) to see their provider. Long wait times posed a barrier, especially for contraceptive methods that require multiple appointments. Lack of insurance coverage for non-Canadian citizens impeded access to healthcare; one participant would travel to their country of citizenship for affordable contraceptive care.

4. Discrimination in Healthcare settings

Disclosing gender diversity to healthcare providers was seen as inviting discrimination. Discrimination was heightened for those who were not assumed cisgender, white, or did not have Canadian citizenship.

“It does feel like add a layer of stress […] just like, I act very white when I’m around people who don’t like acknowledge my Asianness […] I’ve gotten really good at compartmentalizing myself and so, my gender nonconformity is like, just another part of that.”

The historical and ongoing systemic medical violence against Indigenous peoples, Black people, and other people of colour made contraceptive care environments feel unsafe, deterring racialized participants from contraceptive care.

“I think it’s just, like, racialized medical things […] thinking about [the] medical experiments on black people, especially black women. And then I think about Indigenous women being forcefully sterilized – sterilized! And they’re just like – I just feel like there’s so much uncomfiness when it comes to AFAB people’s bodies in the medical system and [specifically] contraception, […] I feel like I carry that anxiety with me in every interaction I go [through] for my contraceptive health.”

Past experiences and fears of discrimination prevented participants from seeking contraceptive care. Participants relied on their community networks to find trusted providers, and were less likely to see unfamiliar providers (e.g., in walk-in clinics). Participants were less likely to advocate for their healthcare needs in hostile environments (e.g., staff microaggressions, rejection of patients’ gender identity, misgendering and deadnaming, denial of healthcare, and physical or verbal abuse).

“I’m also straight up terrified to [disclose my gender] just because I’ve – so many people react so poorly, that I don’t – I’m so scared to lose a doctor in BC right now that like if I lose her or she like thinks it’s a psychiatric issue like […] I’m concerned, sometimes, if I fill [out my gender on forms] that it’ll affect the level of care I get. Or how I’ll be treated […] I need a doctor in BC – you can’t find a GP right now, are you kidding me?”

Participants described exhaustion from constant self-advocacy – persevering through microaggressions, dismissiveness, hostility, denial of healthcare, and verbal and physical abuse. No participant filed reports of discrimination for fear that their provider would not be held accountable and their report could become public, endangering future healthcare.

“You can’t anonymously-anonymously submit [a complaint] […] What if that, like I don’t know, [if] that info is mishandled? […] [what] if that info like gets back to the doctor? […] I didn’t need that added stress, so that’s why I didn’t pursue anything.”

5. (Dis)Trust of Healthcare Providers

Participants gathered information from their community on how different contraceptive side effects would influence gender dysphoria/euphoria. Participants did not trust healthcare providers to provide accurate or relevant information; often, participants had to educate their healthcare providers on their needs. Providers were not trusted to consider the impact of contraceptive methods on comorbidities (e.g., mental health and autoimmune disease).

“[…] now I don’t trust what my doctors just straight up tell me, because people have warned me that the [IUS] was like this. People warned me about the pill and all this stuff. So now I just want first-hand experiences [from my community].”

Lack of representation of 2SLGBTQIA+ and racialized communities among healthcare providers hugely impacted participant experiences of psychosocial safety; participants described this as leading to feeling “like an interesting thing at the zoo.” Many participants were uncomfortable with their power dynamic with providers that were white, cisgender men, especially if the provider was less educated on gender diversity or displayed less consideration for their bodily autonomy. Ultimately, participants did not trust healthcare providers to protect their autonomy.

6. Participants’ Recommendations for Contraceptive Care

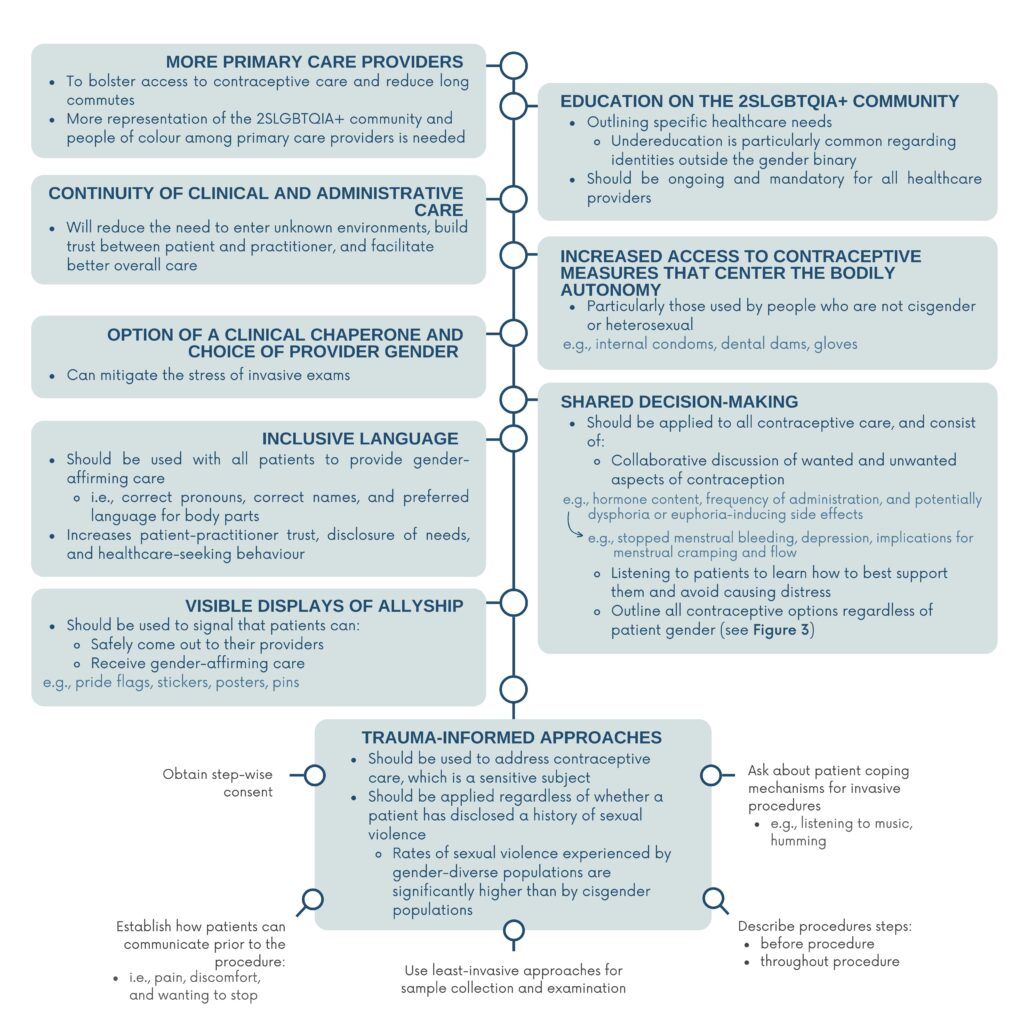

Participants offered detailed recommendations for contraceptive care appropriate for gender-diverse people (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Participant Recommendations for Contraceptive Care: more primary care providers, healthcare provider education, continuity of care, access to contraceptives, clinical chaperones, inclusive language (for patient disclosure and health-seeking behaviour), shared decision-making, and trauma informed contraceptive care in the context of prevalent sexual violence.

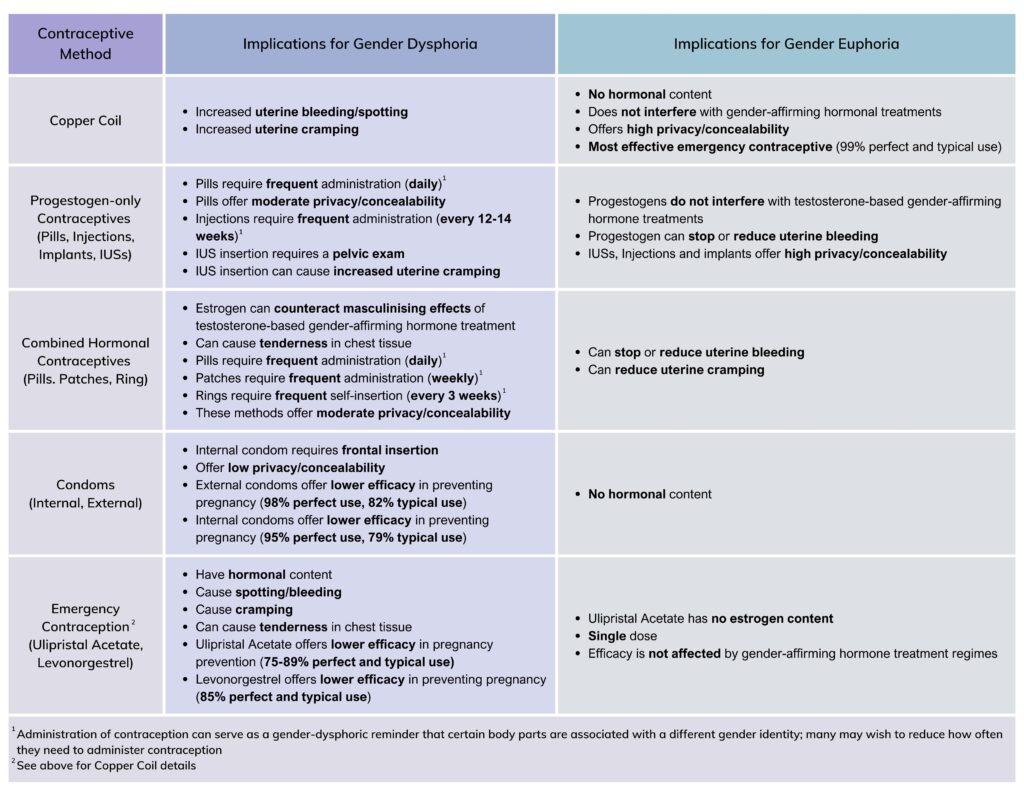

Figure 3. Contraceptive Choices: FSRH Guidelines: Contraceptive Choices and Sexual Health for Transgender and Non-Binary People, Krempasky et. al

7. What Does This Mean for Contraceptive Care?

Gender-affirming care saves lives, in all healthcare sectors. Contraceptive care can be tailored to the needs of gender-diverse patients and contribute to positive experiences, including gender affirmation.

It’s the individual workers. I try and keep faith […] I don’t go into it trying to manifest that I’m going to have a bad experience […].”

Making contraception free and freely accessible is a first step toward accessibility, and more must be done to ensure that gender-diverse communities can trust that they will receive appropriate and affirming contraceptive care.

Acknowledgements & About the Author

Thank you to my supervisor and principal researcher, Dr. Julia Bailey (she/they), and co-supervisor Dr. Anne Lanceley. The people who participated in this study honoured us by sharing their experiences. We are profoundly grateful for their vulnerability and trust. Thank you for giving us your time and energy; thank you for teaching us.

We acknowledge and respect the Songhees, Esquimalt, and W̱SÁNEĆ peoples and the Hən̓̓qəmin̓əm̓ and Sḵwx̱wú7mesh speaking peoples on whose traditional, ancestral, and unceded lands this study took place. To learn more about how to actively contribute to Truth and Reconciliation, visit the Reconciliation Education website.

Thank you to the people at the University of Victoria’s Office of Indigenous Academic & Community Engagement for taking the time to help us write a respectful land acknowledgement.

This project was approved by University College London’s Research Ethics Committee (UCL Ethics ID: 22083/001) and received a waiver from Research Ethics BC in Canada.