To be or not to be (open) – that is the question. Coming to terms with a new diagnosis, prognosis and the impact on your future life and career is hard enough. Taking the initial step of identifying as a disabled trainee can be extremely challenging, particularly once you become aware of the potential reception and repercussions.

The external focus on equality, diversity and inclusion, as advocated by several organisations including the BMA and the GMC, does not always translate into the day to day culture of the organisations in which we train and work.

We may be fearful of speaking out, at least until we reach the comparative safety of having completed training, in case we are told that with our “issues” we “just aren’t cut out for medicine”.

We are sharing our knowledge and experiences as we know we are not alone. There are those who cannot speak up and we hope to raise awareness to pave the way for positive change.

Long-term sickness absence poses significant challenges to the NHS and is associated with increased likelihood of staff leaving the service, placing additional strain on an already struggling system. Although sickness absence rates in doctors are lower than other professions, resident doctors experiencing long-term sickness or acquired disability can face major issues.

Inclusive healthcare leadership must encompass robust strategies for supportively managing individuals with disability or chronic health issues. Whilst the challenges are numerous, we have chosen to focus on potential solutions and have divided the difficulties into three areas:

Disclosure of Health issues

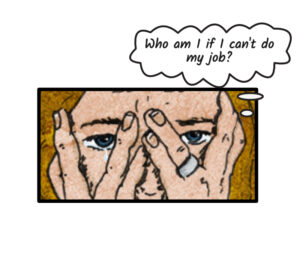

Imagine, if you will, that you are a resident with a health condition. Disclosure must begin with an internal recognition that there is a problem. It is difficult acknowledging that your health issue may affect your ability to practise, with competency based training and the impact on your professional identity.

Initially, you may not have a diagnosis; merely symptoms or a situation of presumed short-term sickness which either fails to improve or deteriorates. You must then consider Good Medical Practice obligations outlined by the medical regulator, risks to yourself and others, and balance this against duty of care for patients, taking appropriate professional advice from your own doctor/health professional.

We know from experience that this can be isolating and worrying to navigate. An appreciation that you are not alone is vital.

So let us tell you now; You are not alone.

What is needed though, is signposting to appropriate professional services, peer support groups or charitable organisations. Awareness of possible Equality Act 2010 applicability may help, although it can be a struggle to perceive yourself as disabled, especially if newly diagnosed, and in any case, this is a legal not a medical decision.

You must then disclose to line managers or trainers. Some may not know how to approach you, as you no longer fit the ableist model of Medicine, i.e. the concept of the doctor as perfect and anyone with flaws no longer fitting in.

Promotion of a compassionate culture amongst peers and supervisors demonstrated through actions, such as enquiring about and supporting access needs rather than rhetoric is essential for the provision of robust support, as is taking steps to address the stigma associated with disability/health problems affecting a medical professional. This stigma is still very real and sadly ubiquitous.

Navigating the sickness absence process

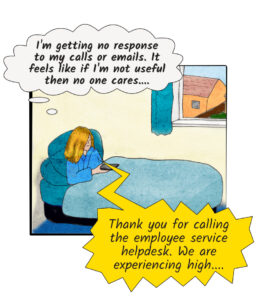

In the UK, residents frequently rotate between trusts as part of training. Sickness absence processes may be inaccessible, unclear or vary between institutions. As we can attest, it is easy to feel extremely vulnerable. As healers we often adopt a servant leadership position, effacing ourselves and our needs for the needs of others, so advocating for our own needs whilst unwell can feel unfamiliar. A lack of response to calls and emails can feel as though you don’t matter if you are no longer useful, whilst a lack of clarity about processes or financial implications can make what is already an exceptionally difficult time even more stressful and confusing.

Potential solutions include raising awareness of relevant contacts during induction. We often feel indestructible….

Until suddenly we are not.

It is therefore vital that processes and policies are reiterated in cases of sickness and are clear and easily accessible. The use of mobile apps or infographics could provide a user-friendly summary detailing simplified points for both trainer and resident.

Accessing Occupational Health (OH) Services

As a resident with a significant health condition or disability you should require occupational health (OH) input. You may experience differential access, delays or other barriers, such as limited availability of suitably trained OH clinicians. There is also the question of who should refer you, with variability between employers. Often, line managers must request OH assessment to be able to receive a report. This report usually outlines recommendations, including “reasonable adjustments”, shared with both resident and referrer. However, these recommendations are often not forwarded on rotation.

We invite you to imagine how it feels if each time you rotate, you must navigate this afresh, often with limited notice for appointments, leading to delays in the issuing and implementation of recommendations. Add to this the frustration of being told that pre-employment processes including OH referral cannot begin until a rotational training allocation grid is finalised, something you cannot control.

You might not need to imagine this. This might be something you are living through right now.

Sharing these OH reports could help identify challenges such as an unsuitable rotation or a practically unfeasible adjustment and facilitate alternatives. Provision of information about sources of support, equipment and funding would also assist with implementing adjustments. Greater transparency about referral processes is essential. We need quality-assured, accredited and reliable OH provision, preferably using experienced assessors with an understanding of the challenges faced by residents.

Rotational training may result in residents with complex health needs lacking long-term OH oversight of their condition and the impact on work and training. A central point of contact to enable timely review could benefit both residents and employers, providing continuity and enhanced efficiency. It can be helpful to have a direct contact responsible for coordinating and supporting with whom residents can liaise as appropriate.

Conclusion

In writing this, we have reflected on our own internalised ableism. We acknowledge it feels challenging and dangerous to speak up, and far safer to stick to facts and potential solutions to the issues faced by those working or training with health issues/disability.

The idea that medicine is only for self-sacrificing superhumans is a fallacy. We have much to offer, and our insights into the psychosocial aspects of disability and disease are of great value in our work, in our leadership, and not just for patient care.

Healthcare training and leadership would benefit from a move towards greater inclusion of those with health needs or disability.

This starts with robust strategies for access to occupational health and an environment where ableism can be freely challenged without fear of repercussions for one’s future career.

Authors

Miss E Rhiannon Richards

Miss Richards is a General Surgery trainee whose work as a Leadership Fellow has evaluated the regional and national variation in provision for PGDiTs requiring a complex phased return. She continues to work to raise awareness and improve processes for trainees with health issues and disabilities. She also has experience of training and working in the NHS with a health issue.

@Rhianno42224910

Dr Helen L Kroening

After entering Medicine as a mature student Dr Kroening gained both professional as well as personal experience of training and working in the NHS with a chronic health condition. In her current role, she is learning more about the management and systemic aspects in addition to the medical side, whilst also aiming to provide appropriate support for colleagues working/training in healthcare despite health challenges.

Declaration of interests

I have read and understood the BMJ Group policy on declaration of interests and declare the following interests: The authors are both PGDiTs who have experience of training with a health condition. There are no financial or other interests to declare.