“The purpose of knowledge is action, not knowledge” Aristotle

However, it is also possible that this action, sanctioned by Aristotle can prove advantageous for some sections of society because of the concept of social engineering, which is a form of social planning. It can be understood as – using knowledge and resources ‘to better’ certain citizens and exclude other from benefitting in society. We have ample evidence for the impacts of social determinants of health, health inequalities, inequity, and racism, yet, we have little action that makes a difference to the lives of individuals and groups who have protected characteristics who are being impacted every day in our organisations and society. Even now, especially now, the impacts of colonialism still affect our society, our institutions and our organisations and still provide rules that structure our existence.1 Despite accumulating, over decades, literature and evidence of the different kinds of injustices and their manifestations, our knowledge has not translated into organised action or accomplished the needed reform in our society. Health inequalities and multiple conditions are both strategic priorities for the Government and the NIHR. The underlying drivers have been identified as socioeconomic disadvantage and reinforcing factors. These factors are intersect and create ethnic inequalities in multiple conditions. The NIHR has highlighted in the quote below that:

“It is possible that racism and multiple forms of discrimination can intersect with demographic factors (e.g. age, gender, and/or sexual orientation) resulting in disadvantage in accessing key economic, physical and social resources for some, thereby, leading to socioeconomic and health inequalities. In turn, these inequalities can result in higher prevalence of some health conditions which may then accelerate the development of MLTCs in some minoritised ethnic group populations.”2

Racism and consequential discrimination, this includes people from disadvantaged backgrounds, minority ethnic groups, and those with serious mental illness. Experiences of health services also differ. The individual needs of disadvantaged groups are often neglected or even made worse by services’ responses. Racism which will be utilised as a lens to understand how much needs to be done in just one of these areas.

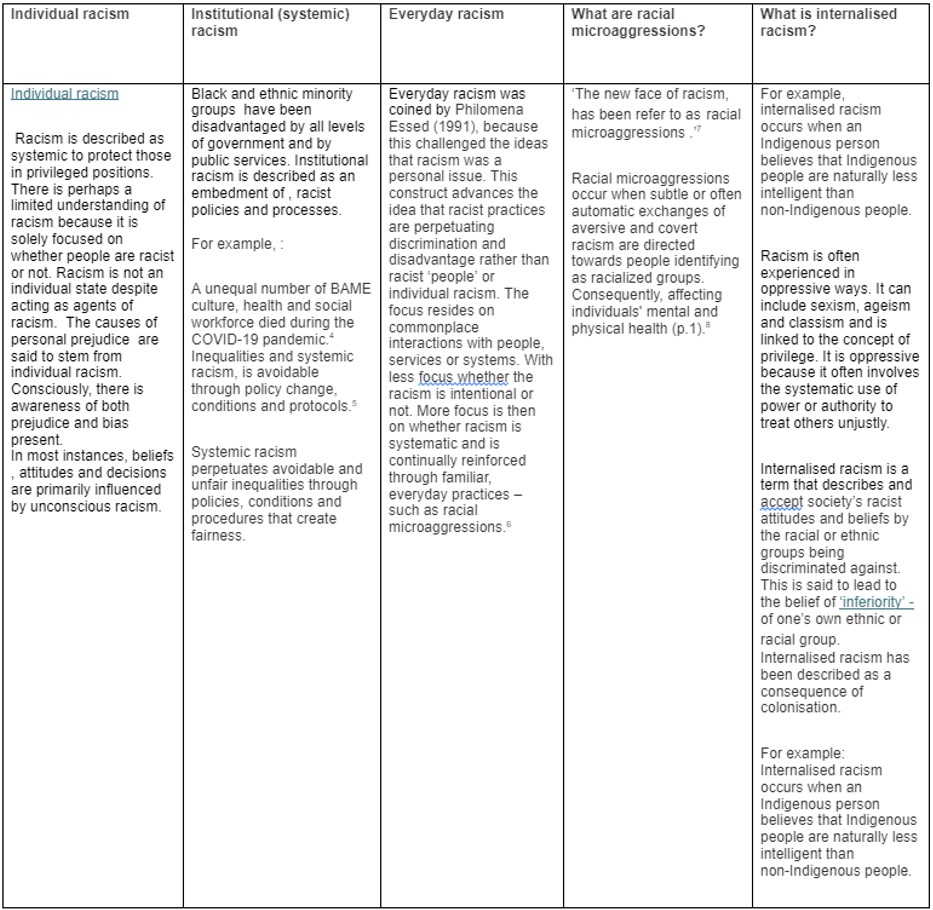

Adwoa Danso and Yaa Danso, suggest that bias and false beliefs are built on stereotypes that stream into the networks within our society. See table. 1 for the racism and its various manifestation definitions.

Table. 1 Racism and its various manifestations (table adapted from information Future Learn)

In my conclusions and quest for evidence throughout this series on social justice which ran through 2023-2024; I look to Susan T. Fiske, in her chapter Are we born racist? She writes that in her own lab, she showed white study participants a series of photos, some of white faces and some of black ones. She gave them two seconds to answer of the three questions about the people in the photos – whether they were over 21 years, whether they had grey dot on their face, or whether they liked a certain vegetable. When participants had to decide if the people in the photos were over 21, she saw a spike in their amygdala activity, similar to what had been found in other studies.9,10 But when they looked at these faces to judge what kind of vegetable the person would like, or when they were looking for a grey dot, their amygdala activity was the same as when they saw white faces. So, Susan’s work indicates that in her study, when participants had to place others into a social category – even if it was by age, not race – they saw black faces differently than white faces. But the grey dot exercise showed it was possible for whites to look at black faces without getting this effect. She further showed that, more importantly for everyday interactions, when participants were prompted to judge these people as individuals – individuals with their own unique tastes and preferences – they reacted no differently to black faces than they did to white ones. Similarly, in Susan’s Lab – brain scans indicated that people stop dehumanising homeless people and drug addicts when they are made to guess what these people would like to eat, overriding the fear produced by the amygdala by triggering empathy – and making the people seen as people

So, to summarise, what this research is telling us – is that individuals and the environment can interact for good or ill, therefore producing social conditions which can reduce prejudice, just as they can foster or exarchate it. Simply, the study showed an overriding of fear which was produced by the amygdala by triggering empathy – and making the ‘people be seen as people.’

What is scarily true about our society is that – these negative attitudes are often automatically activated and can influence a person’s behaviour without conscious volition. The inequality will inevitably lead to poor outcomes in health and social care for certain groups impacted by racism, not just seen within healthcare establishments. Clearly, this can have widespread and stark implications on healthcare outcomes within minority communities we see today. (Please see table. 1 for racism and its various manifestations. Susant T. Fiske, also suggests that both science and history have shown that people will nurture and act on their prejudices in the worst ways when they are under stress, pressured, or need approval from authority.

Why we should fight?

When reading to the complete end of Are we born racist, I felt it deeply poor of our society to be so segregated, and like sociologist Doug Massey, (the husband of Susan T. Fiske), concludes – if our society is to remain so segregated – then all else follows!

I too feel from a healthcare lens – segregation is a mechanism for one section of society to use against another to protect against their fears, perhaps to let others “be equal” in this system and so all else does follow, see below:

- The less fortunate are exposed to violence and disorder,

- Receive inferior education,

- Have fewer local job opportunities

- Lack of constructive role models 11

Well, if you were all thinking – so why did I select the work of Susan T. Fiske to conclude this series – well to be honest, in racism discourse she stands out for her conviction and positivity, which hit me hard because sometimes I feel reality plunges me into a pit which I eventually, happen to dig myself out of – so, I can almost feel the hope and certainty in her words. I recommend you read in her own words below, as I wish to leave you all on this journey with a little sprinkle of her hope,

“Once we understand how automatically people fear difference, dehumanise the less fortunate, and demonize the Other (or ‘not us’)., we can better appreciate how these forms of segregation can perpetuate themselves and why we must fight against them. The science of human prejudice suggests that if we’re informed and persistent, this fight we can win.

Thank you all deeply for reading. We at BMJ Leader hope you take part in online discussions with the authors of the forthcoming pieces on their chosen online platforms. We wish everyone working in health inequalities and social justice all the best for their work to bring ‘actionable change’ which is a necessity for all leaders in all organisations and institutions worldwide.

References

- Kirenci AI. Book Review: The New Age of Empire: How Colonialism and Racism Still Rule the World by Kehinde Andrews. EU Foreign Aff. 2021;

- NIHR Evidence. Multiple long-term conditions (multimorbidity) and inequality- addressing the challenge: insights from research. 2023 Sep 20;

- Gross CP, Essien UR, Pasha S, Gross JR, Wang S yi, Nunez-Smith M. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Population Level Covid-19 Mortality. medRxiv. 2020 May 11;2020.05.07.20094250.

- Kline R. After the speeches: what now for NHS staff race discrimination? [Internet]. BMJ Leader. 2020. Available from: https://blogs.bmj.com/bmjleader/2020/06/13/after-the-speeches-what-now-for-nhs-staff-race-discrimination-by-roger-kline/

- Kline R. Time to change the paradigm [Internet]. BMJ Leader. 2020. Available from: https://blogs.bmj.com/bmjleader/2020/08/22/time-to-change-the-paradigm-by-roger-kline/

- Essed P. Understanding Everyday Racism: An Interdisciplinary Theory Toward an Integration of Macro and Micro Dimensions of Racism. 1991;

- Sue DW, Nadal KL, Capodilupo CM, Lin AI, Torino GC, Rivera DP. Racial microaggressions against black americans: Implications for counseling. J Couns Dev. 2008;86(3):330–8.

- Khan N, Hafeez D, Goolamallee T, Arora A, Smith W, Shankar R, et al. Racial Microaggressions in Healthcare Settings: A Scoping Review. BJPsych Open. 2023 Jul;9(S1):S7–8.

- Phelps EA, O’Connor KJ, Cunningham WA, Funayama ES, Gatenby JC, Gore JC, et al. Performance on indirect measures of race evaluation predicts amygdala activation. J Cogn Neurosci. 2000;12(5):729–38.

- Wheeler ME, Fiske ST. Controlling racial prejudice social-cognitive goals affect amygdala and stereotype activation. Psychol Sci. 2005;16(1):56–63.

- Kervyn N, Fiske ST, Yzerbyt VY. Integrating the stereotype content model (warmth and competence) and the Osgood semantic differential (evaluation, potency, and activity). Eur J Soc Psychol. 2013 Dec 1;43(7):673–81.

Author

Dr Nagina Khan, BHSc, PGCert, Ph.D.

Nagina is a Senior Clinical Research Fellow in Primary Care, Centre for Health Services Studies (CHSS), Division of Law, Society and Social Justice, School of Social Policy, Sociology & Social Research, University of Kent. She is the CHSS PGR Lead (interim) and Director of the MSc Applied Health Research Programme, University of Kent.

Nagina’s current research supports the Integrated Care Systems (ICS) to capitalise on emerging existing networks in its research duty and mitigate the current risk of future research being conducted in silos and without focus on priorities and underserved populations. This work will diversify the public voice listened to and strengthen ICS strategic links within local research infrastructure to support evidence-based practice, apply solutions, and spread innovation.

Nagina was a senior postdoctoral researcher and Visiting Researcher, Department of Psychiatry, University of Oxford. She has worked as a Scientist at Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH). Nagina also worked with Touro University Nevada, Las Vegas, US, and with the Royal College of Psychiatrists. Nagina was a Medical Research Council (MRC) Research Training Fellow, her research was centred on complex interventions for people with depression, University of Manchester. Her post-doctoral studies were undertaken at the NIHR School for Primary Care Research, UK focusing on First episode Psychosis in young people using Early Intervention Services. Nagina’s research interests include Medical Education, Professionalism, Social Justice in Healthcare, Complex Interventions for Depression, First episode Psychosis in Young People, Culturally Appropriate Mental Health Care, Women’s Mental Health, Incentivisation Schemes (P4P) in Healthcare for HICs and LMICs and Global Health. Nagina is the Associate Editor at BMJ Mental Health, she is also the BMJ Leader Editorial Fellow and was an Editorial Board Member of the BioMed Central Medical Education Journal.

Declaration of interests

I have read and understood the BMJ Group policy on declaration of interests and declare the following interests: none.