Following on from the powerful blog “After the speeches…” that outlined actions needed to reduce discrimination, we are delighted to publish part four of a ten part blog series by Roger Kline with suggestions on how to tackle structural racism in the NHS.

For decades NHS employers have largely assumed that having policies, procedures and training in place were the cornerstone of making it safe and effective for staff to raise concerns, to challenge bullying, harassment or discrimination, or to improve recruitment practices. In doing so they were following the NHS Employers Guidance on bullying at work (2006-2016) which stated

“Employers can only address cases of bullying and harassment that are brought to their attention.”

Just before this Guidance was withdrawn, an Advisory, Conciliation and Arbitration Service (ACAS) evidence review explained why this approach was doomed to failure for bullying:

“In sum, while policies and training are doubtless essential components of effective strategies for addressing bullying in the workplace, there are significant obstacles to resolution at every stage of the process that such policies typically provide. It is perhaps not surprising, then, that research has generated no evidence that, in isolation, this approach can work to reduce the overall incidence of bullying in Britain’s workplaces.”

This 2015 review concluded instead, in contrast to the then dominant NHS Human Resources (HR) paradigm, that proactively changing organisational “climate” was the key to reducing bullying.

The NHS has a whole range of measures developed over two decades seeking to protect staff who raise concerns about their duty of care or about unlawful or unsafe activities or treatment. Francis (2015) however, found that relying on staff being brave or foolish enough to raise concerns was not working. He also noted in detail evidence suggesting BME staff were less likely to be listened to when they did raise a concern than White staff were, and more likely to be victimised. As Francis put it, the real solution to whistleblowing victimisation is make it unnecessary rather than inserting procedures and policies to make it easier and safer.

Discrimination

Across UK employment, Hocque found that although four in five workplaces had an equal opportunity policy many are ‘empty shells’ and lack substantive practices to deliver equality commitments. Kalev (2006), in a large scale analysis of US equality initiatives, concluded that “diversity training” was the least effective means of increasing the proportion of staff with protected characteristics in more senior positions and that

“Broadly speaking, our findings suggest that although inequality in attainment at work may be rooted in managerial bias and the social isolation of women and minorities, the best hope for remedying it may lie in practices that assign organizational responsibility for change. ………Structures that embed accountability, authority, and expertise (affirmative action plans, diversity committees and taskforces, diversity managers and departments) are the most effective means of increasing the proportions of white women, black women, and black men in private sector management.”

Similarly, individual unconscious bias training may improve cognitive understanding but evidence (EHRC 2018) of it improving decision-making is thin.

Reliance on individuals challenging biased processes or outcomes is especially futile in recruitment and development. The NHS People Plan sets out ambitious plans to improve diversity at senior levels and especially for BME staff. For that to happen will require serious improvement in current NHS recruitment and development practice which still largely relies on policies, procedures and training. The most recent published review of recruitment practices from NHS Employers does not give confidence that the need to recruit differently, using data driven accountability, understanding the sources of bias and debiasing processes not people, is sufficiently widespread or understood within NHS HR.

COVID-19

The reliance on an over-individualised approach to risk was evidenced in the NHS approach to COVID-19 risk assessments. Instead of an emphasis on a preventative, proactive approach which could have identified which factors would place staff at greater risk of infection, the initial focus was primarily on identifying which individual staff might be most at risk if they were infected. Individual staff risk assessments were important but insufficient effort went into preventing exposure through identifying whether some staff groups might be disproportionately at risk through organisational factors such as poorer BME staff access to appropriate PPE, agency staff being both at greater risk and being a risk, how safe so-called “safer” areas really were, and whether social distancing was actually possible in many communal areas. Such prevention was possible as witnessed by the absence of fatalities in the most obviously dangerous area, ICU. The staff groups particularly at risk from organisational shortcomings (BME staff) were also those most at risk if they became infected.

A different approach

A different (and better) approach is gaining ground within a growing number of NHS employers, with some national encouragement.

Employers are starting to use analytics more widely to identify and track concerns, triangulating “hard” and “soft” data to locate and understand issues such as bullying, disciplinary action, safe working and discrimination. The best ones emphasise problem-sensing not comfort-seeking and focus on preventative early intervention. The Workforce Race Equality Standard helps that approach, being underpinned by evidence that data driven accountability was crucial, rather than relying on individual complaints.

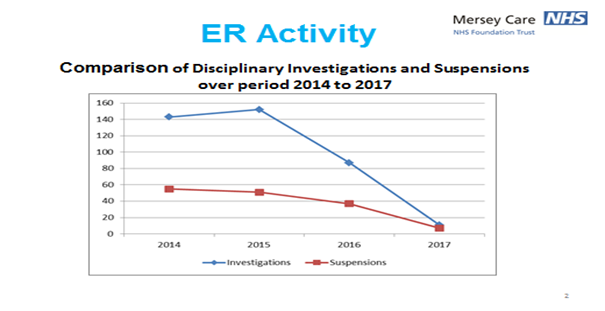

The “just culture” approach is one example of a different paradigm and finds a helpful echo in the NHS People Plan 2020-21. Early evidence suggests it may make a radical difference to organisational culture and patient care, and reduce individual case work arising from the pre-existing HR paradigm as this graph shows:

ER: Employee Relations

Where Trusts have adopted this approach, they have found that introducing managerial accountability alongside psychological safety, so issues can be raised and addressed before they escalate, is a major factor in improving both patient and staff safety – and saving money.

Disciplinary action (16,000 cases in NHS Trusts in 2016-17) consumes vast amounts of management time, tends to emphasise blame not learning and disproportionately impacts BME staff. Common shortcomings were summarised by NHS Improvement (2019) as including

“poor framing of concerns and allegations; inconsistency in the fair and effective application of local policies and procedures; lack of adherence to best practice guidance; variation in the quality of investigations; shortcomings in the management of conflicts of interest; insufficient consideration and support of the health and wellbeing of individuals; and an over-reliance on the immediate application of formal procedures, rather than consideration of alternative responses to concerns.”

Though even this helpful Review bizarrely failed to mention race (though it arose out of Amin Abdullah’s tragic suicide), it encouraged the insertion of accountability and informal early intervention in disciplinary processes, something that has helped reduce the overall number of cases, and reduce the likelihood of BME staff being disciplined.

Conclusion

The policy framework used to tackle toxic NHS work cultures is not fit for purpose and enables discriminatory practices. The “policies, procedures and training” paradigm has no sound evidence base. There has never been a better time to think more radically in ways that will address race discrimination.

Roger Kline

Roger Kline is Research Fellow at Middlesex University Business School. He authored “The Snowy White Peaks of the NHS” (2014), designed the Workforce Race Equality Standard (WRES) and was then appointed as the joint national director of the WRES team 2015-17. Recent publications include) the recent report Fair to Refer (2019) to the General Medical Council on the disproportionate referrals of some groups of doctors (co-authored with Dr Doyin Atewologun) and The Price of Fear (2018), the first detailed estimate of the cost of bullying in the NHS, co-authored with Prof Duncan Lewis.

Declaration of interests

I have read and understood the BMJ Group policy on declaration of interests and declare the following interests: none.