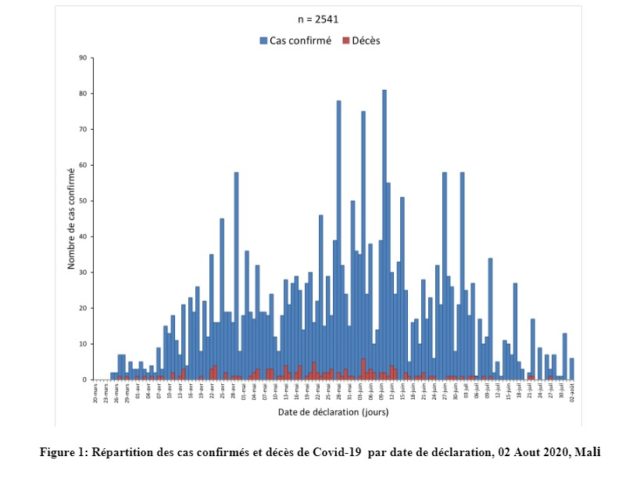

On 25 March 2020, Mali reported its first imported cases of COVID-19. To curb the spread of the disease, the government had quickly introduced a series of initiatives. These were shutting down borders, imposing a nationwide curfew, closing schools, and establishing a call center to report suspected COVID-19 cases and acquire health information. People were asked to practice physical distancing and adopt good hand washing practices. Hand washing stations were installed in markets and places of worship. The government also announced a special fund to support the poorest households with income, essential food, and free supply of electricity and water. To promote the access and proper use of masks by everyone, particularly by the most vulnerable, the “One Malian, One Mask” initiative was unveiled. As of 2 August 2020, the West African nation officially recorded 2,541 cases, with 124 deaths and 1,943 recoveries.

Despite this relatively low number of COVID-19 cases in the country the risk of a surge in the number of infections remains. Containment measures are only effective as long as people comply and, in Mali, compliance has remained a challenge. Embraces and handshakes are still given, mini-buses and taxis are packed, mosques and markets are attended by many, and masks are worn by a minority.

Several contextual factors can explain this low compliance. In these times of extreme dryness, most households do not have adequate access to water. Nearly 45% of Malians live below the poverty line, challenging their capacity to buy soap and masks. Income-constrained individuals are mostly found in slums, where physical distancing and access to clean water are challenging. Additionally, staying at home to prevent exposure to the virus is not possible for the majority of Malians who work in the informal sector and live hand to mouth.

After Bamako, the capital city, the largest outbreak of COVID-19 is concentrated in the Timbuktu region, the most religious part of the country. There, people continue to attend mosques in high numbers without masks or physical distancing. When the Ministry of Health (MoH) expressed the need to close the mosques, it was met by much resistance from religious leaders.

Many still think that the disease is not real or dangerous. The night curfew created the public perception that the virus may only be contagious during night. Some believe that the government is fabricating data to secure international funds, and use it to sustain the lifestyle of politicians. As such, the term “Corona Business” has been coined.

The response to COVID-19 has amplified the population’s discontent with the government, which is deeply rooted in years of growing insecurity ,economic concerned, and perceived political corruption and social injustice. Since early June, a series of protests demanding the resignation of the government for, among other reasons, the inability to provide masks to everyone and to deliver financial and food support to those who suffered a loss of income because of the pandemic has also been organised

The population’s distrust of the current regime—or in other words, the absence of strong political leadership—ultimately jeopardises health officials’ efforts to halt the spread of COVID-19 in communities. Because the MoH can be perceived as a reflection of the government, communities may be reluctant to follow health officials’ orders. Large gatherings like protests further put many individuals at risk and make contact tracing very challenging. More importantly, the demonstrations have much appealed to the youth who are more likely to display an asymptomatic or mild form of COVID-19. Having the virus concentrated and dormant within the youth population could precipitate the country into a ‘silent epidemic.’

Since mid-July, there has been a decline in the number of daily detected cases. Still, this apparent drop should be taken with a pinch of salt. Manifestations from June and other above-mentioned factors reinforce the idea that the true extent of COVID-19 propagation could be more important. The MoH should therefore increase the testing capacity at community and facility levels to identify asymptomatic ‘carriers’ of the virus. Currently, tests are conducted on suspected cases encountered in health facilities, and the number of tests/day has widely varied, the highest conducted being around 700.

Measures such as mass face covering, hand hygiene, and physical distancing should be enforced until a vaccine is available. Young, seemingly healthy people need to understand how disregarding preventive measures could put the most vulnerable at risk. The role of trusted bodies such as radio stations and civil society associations in educating the youth on COVID-19 cannot be neglected. In the face of growing civil disobedience, opposition leaders also have the responsibility of raising awareness about COVID-19 and leading by example by wearing masks during demonstrations.

In anticipation of an increase in cases, the MoH should expand health facility capacity by addressing the shortages of beds, medical supplies, and personal protective equipment. Training and financial and psychological support should also be provided to health workers.

In conflict-afflicted areas such as Timbuktu, hardly accessible to the government, adequate and adaptive steps should be taken to ensure that health workers in those regions, and the population they serve, are not left behind.

About the authors

Mariame Ouedraogo is currently working as a research analyst for the SickKids Centre for Global Child Health, where she supports various RMNCH projects across Sub-Saharan Africa.

Moussa Doumbia is a physician and researcher working for the Centre for Vaccine Development (CVD) in Mali. There, he supervises the conduct and evaluation of several studies. He is also the primary research contact in Mali for the SickKids Centre for Global Child Health.

David Zombre is a researcher with expertise in public health and health system research and financing. He currently works as a research analyst for the SickKids Centre for Global Child Health, where he leads the implementation of research studies in Mali.

Conflict of interest: We declare no competing interests

Acknowledgment: This blog responds to a call by BMJ Global Health, in conjunction with the Emerging Voices for Global Health on COVID-19 in Sub-Saharan Africa.