More intense monitoring makes no difference to outcomes in type 2 diabetes and costs a lot more, but not everyone agrees on what should be done in practice.

Carl Heneghan, Ben Goldacre

Glucose self-monitoring with automated feedback messaging in type 2 diabetics not taking insulin makes no difference to patient outcomes and costs a lot more, but not everyone agrees its use should be curtailed. Glucose test prescribing also varies markedly in general practice suggesting substantial savings can be made.

A recent randomised trial, done in 15 primary care practices, compared once-daily and once-daily self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG) with automatic feedback messages to no monitoring at all. At one year, there was no reported difference in glucose control (haemoglobin A1c levels) and health-related quality of life between all three groups.

So, what’s new about this trial?

A Cochrane review, including 12 trials, found that any effect of SMBG is small up to six months after starting and subsides after 12 months of monitoring. In this review, there was also no evidence that testing affects patient satisfaction, general well-being or general health-related quality of life. In an economic analysis, total estimated costs in the first year of SMBG were 12 times more expensive than self-monitoring of urine glucose. Further evidence from an individual patient data meta-analysis also found no clinically meaningful effect of SMBG in non-insulin type 2 diabetics.

This current trial adds to this evidence by showing that if you increase the intensity of feedback by using an automated, tailored messaging service accounting for blood glucose value, time of day, and relationship to food intake – intended to educate and motivate patients – you still do not affect glycaemic control.

How does guidance for SMBG vary?

In 2010, the American Diabetes Association recommended SMBG as a guide to successful therapy; and still recommends SMBG: ‘results may be useful for guiding treatment and/or self-management for individuals using less frequent insulin injections or noninsulin therapies’.

Diabetes UK, agree with the ADA approach: they argue that SMBG should be available based on the individual assessment of need, and that withdrawal in those that benefit, should not occur.

NICE (NG28 – recommendation 1.6.13), however, recommends SMBG should not be routinely offered to adults with type 2 diabetes unless the patients are on insulin, is pregnant or is at risk of hypoglycaemic episodes. SIGN also do not recommend it use [6]

How does SMBG vary in practice?

OpenPrescribing is an interactive web tool that allows you to assess prescribing trends for prescription items in the UK (including Glucose Blood Testing Reagents; BNF code 0601060D0) across all GP practices in NHS England, and also to examine the prescribing data of individual GP practices.

The data across the whole country shows that monthly average prescribing for testing reagents has hardly changed since 2010 (see the Figure 1), with spending approximately stable at £14 million a month.

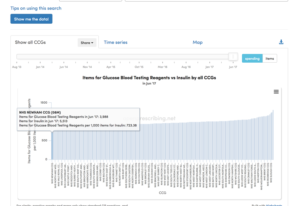

This lack of change could be due to the stable population of insulin-treated diabetics being monitored appropriately. However, assessment of the spend on Glucose Blood Testing Reagents versus Insulin by all CCGs reveals a two-fold variation in prescribing. The bottom CCG, NHS Newham, prescribes 723 testing reagents for every 1000 items of insulin, compared to NHS Bradford City, who prescribe 1,315 test items for every 1000 insulin prescriptions – spending about twice as much on testing £763 vs £349 for every £1,000 spent on insulin (see the Figure 2).

What should we conclude about SMBG?

This new trial shows that the addition of more intense monitoring, through automated feedback makes no difference to type 2 diabetics not on insulin, adding to the overall lack of effect of SMBG.

Health systems should optimise those treatments shown to be effective and disinvest in those interventions with evidence that shows no difference to patient care. Openly accessible sources of real-world data, such as OpenPrescribing, can be used to assess whether clinicians are changing their behaviour in response to new evidence, and identify where there is regional variation in the quality and cost-effectiveness of care.

Figure 2.

Carl Heneghan, Editor in Chief of BMJ EBM, Professor of EBM, University of Oxford, Director of CEBM and

Carl Heneghan, Editor in Chief of BMJ EBM, Professor of EBM, University of Oxford, Director of CEBM and

Ben Goldacre is Director of the EBM DataLab at the University of Oxford

Ben Goldacre is Director of the EBM DataLab at the University of Oxford

Competing interests

OpenPrescribing.net is part of the EBM DataLab, University of Oxford, 2017. BG and CH receive funding from the NIHR SPCR and the Health Foundation for OpenPrescribing.

References

Glucose self-monitoring in non-insulin-treated patients with type 2 diabetes in primary care settings: A randomized trial. JAMA Internal Medicine 2017;177:920-929

Self-monitoring of blood glucose in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus who are not using insulin. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 Jan 18;1:CD005060.