This Guest Blog, by Caoimhe McKenna, David Taylor-Robinson, Sophie Wickham, Benjamin Barr and Rosie Kyeremateng, addresses the highly political issue of defining child poverty, within the UK context.

We would welcome any and many comments on this blog, and via our usual social media channels! (As always, the libellous and frankly spamming will be blocked, but any other comments will be posted.)

The Government’s plan to repeal the 2010 Child Poverty Act, which committed them to eradicating child poverty in the UK by 2020, and dispense with the current definition of child poverty is highly concerning. This was in the context for a recent report which stated levels of child poverty in the UK were “unacceptably high” and expected to rise (CCs, 2015).

Ian Duncan Smith has indicated that the standard definition of relative child poverty (a household income below 60% of contemporary median) will be replaced with measures of ‘worklessness’, family breakdown, addiction, debt and educational attainment. Details of how this ‘new’ definition of child poverty will be formulated, and what the targets are, have not been outlined. This is concerning because an unvalidated and unclear measure of child poverty may be open to political manipulation.

No single measure of child poverty can capture the full picture. One reason the government have cited for ditching the relative income measure of child poverty is that in the context of the 2008/2009 economic recession child poverty appeared to fall. However, this was because the overall UK median income fell. The absolute poverty measure, which is adjusted for inflation, indicates poverty has risen, both before and after housing costs are accounted for (McGuinness, 2015).

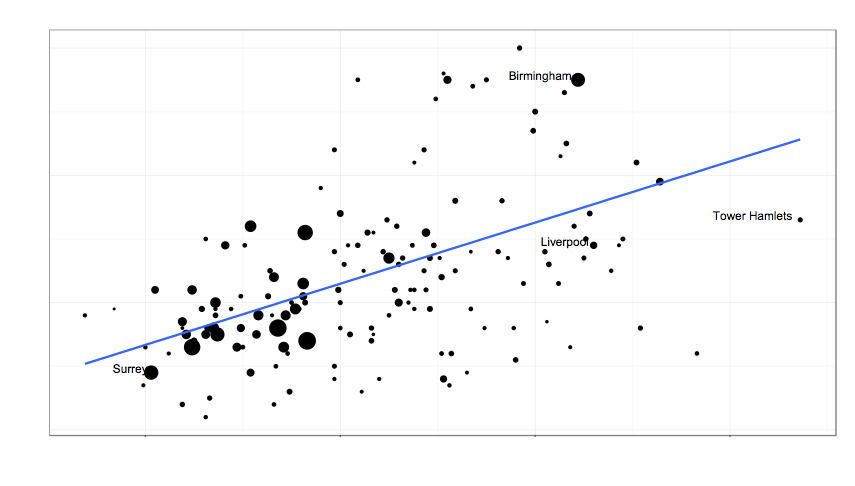

Relative income measures of poverty are an international standard used by the European Union, the Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development, UNICEF and most income-rich countries. The measure is highly correlated with child health (figure 1). Children who grow up in poverty are more likely to have been born prematurely, die within the first year of life, develop obesity, have behavioural problems and perform less well at school (Griggs and Walker, 2008); these adverse risks also extend into adulthood (Raphael, 2011), increasing the risk of poor health and social outcomes across the life course.

But now more than ever a poverty measure based on income is important. The Institute for Fiscal studies have predicted a decade of rising child poverty, unprecedented since records began in the 1960s (Social Mobility & Child Poverty Commission, 2014). The cuts to be announced in the Chancellor’s emergency budget, due to be published on July 8th, outlining a further £12 billion in cuts to working-age benefits are likely to make the situation worse.

The current policy response to the shameful levels of child poverty in the UK appears to be to obfuscate the measure. We suggest that paediatricians should be “up in arms” about the proposed changed. Considering that around 1 in 3 of our patients are already living in poverty (McGuinness, 2015) we must demand real action and certainly not permit any attempt to hide the true scale of the problem.

Figure 1. Infant mortality rate by relative child poverty (<60% median) for upper tier local authorities in England.

– Caoimhe McKenna, David Taylor-Robinson, Sophie Wickham, Benjamin Barr, Rosie Kyeremateng

About the authors

Dr. Benjamin Barr is a senior Clinical Lecturer in Applied Public Health Research at the Department of Public Health and Policy at the University of Liverpool.

References

GRIGGS, J. & WALKER, R. 2008. The costs of child poverty for individuals and society: a literature review, Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

MCGUINNESS, F. 2015. Poverty in the UK: statistics, Briefing paper. file://greenjack/cmckenna/Downloads/SN07096.pdf: House of Commons Library.

RAPHAEL, D. 2011. Poverty in childhood and adverse health outcomes in adulthood. Maturitas, 69, 22-26.