The Doctors’ Book Club

Haruki Murakami’s The Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage

Invoking the ubiquity of sadness, Emily Dickinson writes: “I measure every Grief I meet With narrow, probing, eyes – I wonder if It weighs like Mine – Or has an Easier size.” Universal and elusive, everyone’s grief is both familiar and fundamentally inaccessible to those on the outside. Grief, Dickinson explains, is personal and unique.

In his latest novel, The Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage, Haruki Murakami explores this complex nature of sadness. The story centers on a middle-aged metro station engineer in Tokyo. His life, like the Colorless Tsukuru’s name, is devoid of color, uniqueness, relateability. We learn of Tsukuru’s six-month period of suicidal ideations while studying in the university but neither we, nor Tsukuru, can decipher what pushes him to that level of desperation or what keeps him from taking the plunge.

As the book opens, Tsukuru contemplates that period in his life: “Perhaps he didn’t commit suicide then because he couldn’t conceive of a method that fit the pure and intense feeling he had toward death. But method was beside the point. If there had been a door within reach that led straight to death, he wouldn’t have hesitated to push it open.” We accompany Tsukuru on the quest to understand his own sadness but are never granted access to his mind. After all, how does one relate to the protagonist’s fascination with non-existence: “This world, the one in the here and now, wouldn’t exist. It was a captivating, bewitching thought.” Yet as Murakami traces his journey from adolescence into adulthood, exploring both the degrees of sadness and the way that grief can alienate others, we grow more and more distant from Tsukuru and his world.

Like the speaker in Dickinson’s poem, preoccupied with comparing her own grief to the grief of others—some grieve over death, others over unmet wants—Tsukuru reveals his sadness to be both unique and somehow universal. After all, several other characters’ deaths in the novel can be attributed to suicide, even if Murakami elects to leave those details unnamed (Tsukuru’s best friend Haida, who disappears without a trace after summer holiday, tells Tsukuru the mystical story of embracing death just prior to his disappearance). However, we are never told what Haida’s source of sadness is or if his death is truly a suicide. With Haida, as with Tsukuru, the walls of sadness are simply impenetrable.

Murakami, we conclude, is interested in exploring the complexity of sadness and the various sources that inspire it. In many ways, sadness defines the human condition and is the emotion that we, as healthcare providers, must be comfortable exploring. At the same time, there is an undeniable complexity to despair: sometimes the source of melancholy eludes not only the doctors but the patients’ themselves.

We invite your personal reflections on dealing with sadness in the healthcare setting. How do you approach patients struggling to crystalize the source of their sadness? Does Tsukuru’s pilgrimage seem like a reasonable approach? Would you, as a healthcare provider, ever advise Tsukuru to undertake this journey? Post your thoughts in the comments section below!

Next Month:

We will discuss Anthony Johnson The Orphan Master’s Son.

Question to consider:

-What is the function of using three separate narrators: the loudspeaker, the interrogator, and Jun Do? Are any of the narrators reliable?

-Does the reliability of the narrator change the “truth” of the story?

-What is the role of “reliability” in the clinical context? Is there a difference between “truth” and “fact” in clinical settings?

-Cervantes famously writes that “facts are the enemies of truth.” How does that observation play out in Johnson’s narrative and in clinical practice?

-What do we learn about the nature of suffering from Johnson’s portrayal of Korea? Of the human ability to adapt?

Daniel Marchalik is completing his urologic surgery residency in Washington, D.C. He writes a monthly column for The Lancet and directs the Literature and Medicine Track at the Georgetown University School of Medicine.

Daniel Marchalik is completing his urologic surgery residency in Washington, D.C. He writes a monthly column for The Lancet and directs the Literature and Medicine Track at the Georgetown University School of Medicine.

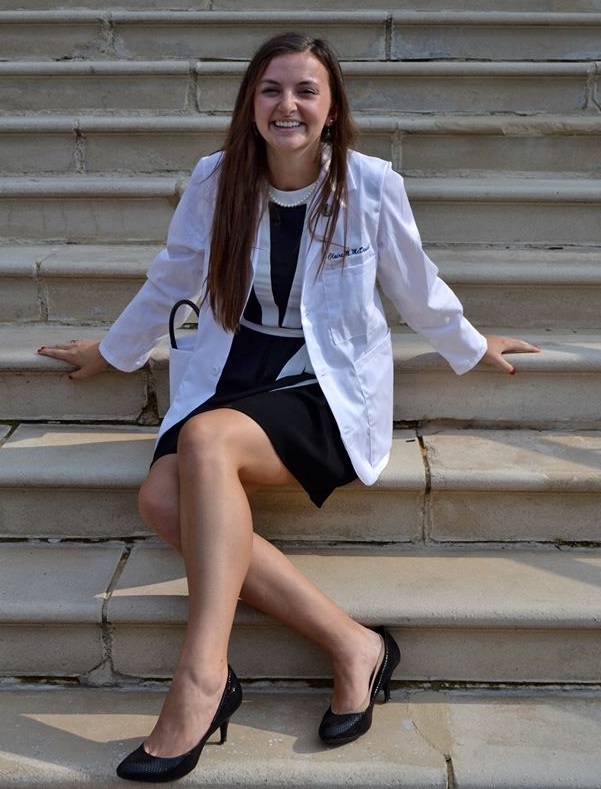

Claire McDaniel is a second year medical student at Georgetown University School of Medicine in Washington, DC, participating in the school’s Literature and Medicine Track. Additionally, she is an MBA candidate at Georgetown University McDonough School of Business.

Competing interests: None declared.