The current dengue outbreak in Delhi came to international prominence following the unfortunate incident of a young couple who committed suicide after their son was rejected treatment by many prominent private sector hospitals in Delhi. Treatment was denied despite the government saying on 28 August that patients should not be denied admission to hospital on account of a lack of beds. Responding to such cases, the Government of Delhi has issued show-cause notices to five private hospitals asking them to explain why they refused to admit the boy and why their registration should not be cancelled.

The current dengue outbreak in Delhi came to international prominence following the unfortunate incident of a young couple who committed suicide after their son was rejected treatment by many prominent private sector hospitals in Delhi. Treatment was denied despite the government saying on 28 August that patients should not be denied admission to hospital on account of a lack of beds. Responding to such cases, the Government of Delhi has issued show-cause notices to five private hospitals asking them to explain why they refused to admit the boy and why their registration should not be cancelled.

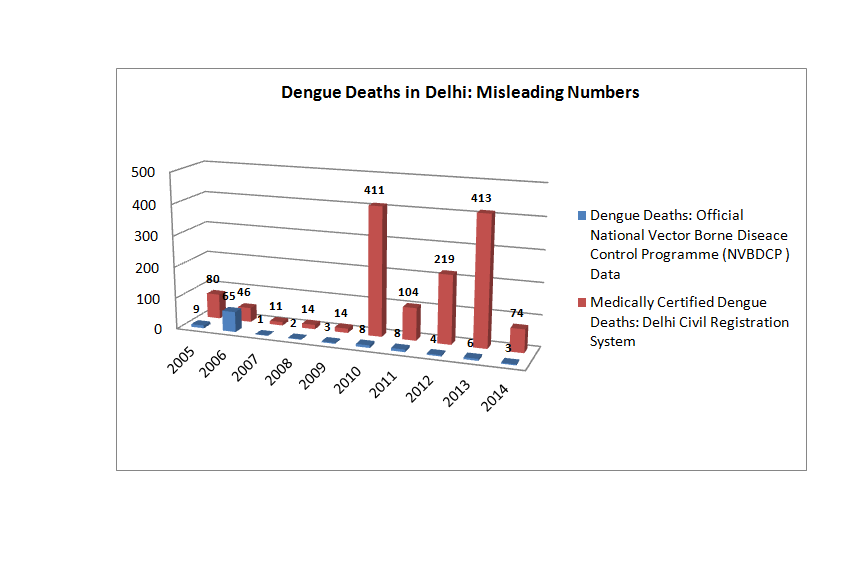

A quick comparison of different sources of data on deaths from dengue fever show that the “official” reported deaths from dengue fever over the last five years (2010-14) in Delhi are much lower than the deaths registered by the civil registration system, as the following graph shows. Of the 1221 deaths from dengue fever that were registered in Delhi between 2010 and 2014, only 29 entered the official system. This is actually not surprising given the Indian situation, as studies have shown that official estimates of the annual incidence of dengue fever in India are lower than the actual number by a staggering 282 times.

Dengue fever affects most of the metropolitan cities and towns in India, where the healthcare delivery systems are better than the rural areas, however, the preparedness of the system against it may be impacted by the level of massive under-reporting of cases and deaths.

It comes as a surprise that the febrile, high decibel news coverage on dengue fever—which frightens people rather than informs them—focuses on official statistics alone. The numbers being discussed in the media are in no way near reality. Judging purely by airtime, however, dengue outbreak in Delhi has perhaps become yet another instance of the media’s urban bias playing itself out. As two prominent commentators wrote, the story of an Adivasi in Odisha who was allegedly forced to sell his two-month-old son for Rs 700 to buy medicines for his sick wife earlier this year was relegated to the inside pages of newspapers. It seems no channel picked it up.

Private Sector Woes of Delhi

In most cases dengue fever is self limiting, but a small proportion of patients need to be hospitalised. It often happens that many patients are admitted to hospitals who didn’t need to be, while some patients who needed hospitalization were admitted too late, or not admitted at all.

Profiteering in times of distress is nothing new to Delhi’s private health sector: even those which claim to be private “charitable” hospitals are notorious. Delhi has a large number of private hospitals, which have received free land and other subsidies from the government to provide free services to poor patients. Over time, these charitable hospitals have become purely commercial entities, dishonouring the commitments made to the government.

A high level committee assigned by the Government of Delhi, headed by Justice AS Qureshi, took a bleak view of the nature of such hospitals which claim to be charitable just to lap up subsidies and have become “selfish, greedy, and exploitative” moneymaking machines. Data from 2014 show that the average total medical expenditure for treatment per case of hospitalisation is higher in Delhi than any other state in India, at Rs 34,658. The India average is Rs 18,268.

For these very reasons, midway through the dengue outbreak, the Union Health Ministry decided to ask the Delhi government to take action against any overcharging by the private hospitals. On 16 September, Delhi’s Directorate of Health Services issued an order against private hospitals and laboratories overcharging, and implemented ceiling prices for dengue testing. Another advisory on the same day allowed the private hospitals and nursing homes to increase their bed strength by up to 20 per cent on a temporary basis for two months.

As of 21 September, the press has reported that while the death toll has “risen” to 22 this season, the deputy chief minister announced that the health situation is now better and the government is winning the battle against dengue. However, activists do not take these numbers seriously. Advocate Ashok Agarwal, a member of a Delhi high court-appointed panel to oversee the implementation of the EWS scheme (beds reserved for patients from “economically weaker sections”) in private hospitals announced on social media that the Delhi Government’s dengue death figures are incorrect and that 23 dengue deaths have happened in one hospital alone. The director of another hospital in Delhi is on record saying that at least seven dengue deaths had taken place in his hospital alone, as of 17 September.

A look at civil registration data reveals that dengue strikes Delhi at regular intervals. With more money already put into health, the current Delhi government—only in its first year of rule—may be better placed to fight any dengue outbreak in the future. However, any effort towards containing contagion should begin with having correct numbers—of cases and deaths—and a long term plan to align the private sector in the state with the broader public health goals of society.

Oommen C. Kurian is research coordinator, Oxfam India.

Competing Interests: In 2013, the author conducted a comprehensive study of Mumbai’s private charitable hospitals based on data over three years which found large scale flouting of laws, and that only 2% of the large hospitals in Mumbai provided poor patients with the legally mandated 10% of bed days.