The grapheme <a> is used as a symbol for the phoneme /a/ when it is pronounced as the low front unrounded form of the vowel, as in the Scottish pronunciation of “back.” In the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) it is called Cardinal vowel number 4. The grapheme that looks like a handwritten version <ɑ>, Cardinal vowel number 5, represents the low back unrounded version; it has a slight hint of an o in it, but probably only phoneticists can reliably distinguish the two sounds.

The grapheme <a> is used as a symbol for the phoneme /a/ when it is pronounced as the low front unrounded form of the vowel, as in the Scottish pronunciation of “back.” In the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) it is called Cardinal vowel number 4. The grapheme that looks like a handwritten version <ɑ>, Cardinal vowel number 5, represents the low back unrounded version; it has a slight hint of an o in it, but probably only phoneticists can reliably distinguish the two sounds.

But the letter a is also a word in its own right, the so called indefinite article. Originally it was “an,” a form of the Old English word for one, án, but by 1150 it was reduced to “a” before consonants (for example a word) and before vowels that are pronounced as consonants (for example a eucalyptus, a one, a urinal); “an” was retained before words beginning with a vowel (an operation) or an h (an hour), even if aspirated (an historian), although not nowadays.

In about the 15th century both forms were commonly written in combination with the noun as a single word, for example aman or anoke. When a century or so later they became separated again, there was often uncertainty about where the division should occur. In some cases this led to spurious words (for example, a nox), a few of which persisted, becoming part of the language, as some examples show:

• adder (OE naedre);

• aitchbone (the rump bone in cattle; OFr nache, Latin natis, buttock);

• apron (OFr naperon, from Latin mappa, a table napkin);

• auger (OE nafu-gar, something that pierces (gar) the nave of a wheel);

• umpire (OFr noumpere, one without equal);

• newt (OE an efeta);

• nickname (OE an ekename, an alternative name).

In the first five examples the n was lost from the noun to the article, and in the other two it happened the other way round.

In a variant of this, “for then once” became “for the nonce.” By the same process, in Scotland “mine own self” became “nainsell,” sometimes used jocularly to mean a Highlandman. And when the Fool calls Lear “nuncle,” he means “mine uncle,” although perhaps he also has “nanunculus,” a little man, in mind.

When the Arabic word “naranj” was converted in this way to “orange,” it was at least partly influenced by the Latin aurum, gold. Some Indo-European languages retain the n (Azerbaijani narıncı, Spanish naranja), some do not (French orange, Dutch oranje). In Spanish “naranjo” is an orange tree. The Naranjo probability scale, a method for determining the likelihood of an association when a drug is suspected of causing an adverse reaction, was devised by the late Claudio Naranjo, a clinical pharmacologist in Toronto. His method, although problematic, continues to be used.

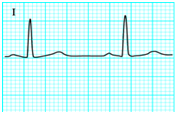

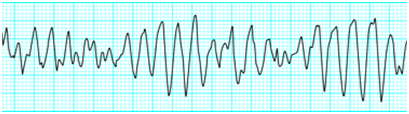

The interaction of grapefruit and grapefruit juice with drugs that are metabolized in the gut and liver by the oxidative enzyme CYP3A4 is well known. For example, the antihistamine terfenadine was removed from over the counter sales some years ago because grapefruit inhibits its metabolism, and that can lead to dangerous cardiac arrhythmias (picture). What is less well known perhaps is that the same interaction can occur with other members of the citrus family, including limes and Seville oranges. Other types of oranges seem to be innocent.

The normal electrocardiogram (left) and the typical type of abnormal cardiac rhythm (right) that occurs during interaction of grapefruit juice with drugs such as terfenadine.

Originally, the process by which these linguistic changes occurred was called provection, but that covered only those cases in which the letter n moved from the article to the noun and not the other way round. In 1914 therefore, the grammarian Otto Jespersen coined a word to cover both processes; he called it metanalysis. Not to be confused with the form of systematic review called meta-analysis, which is the definite article.

Jeffrey Aronson is a clinical pharmacologist, working in the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine in Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences. He is also president emeritus of the British Pharmacological Society.

Competing interests: None declared.