Last week the annual celebration of the passing of the final MBChB exams took place at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. It is a tradition. Saturday morning, after a week of exams, the successful students gather in the lecture theatre. They all proudly wear new white coats given by the Faculty of Medicine and spend a few hours listening to words of wisdom from the faculty dean, the dean of education, the chairman of the department of surgery, and other luminaries. The occasion is relaxed, it is fun, it is a celebration (see photo).

My friend and colleague, Professor Shehkar Kumta, surprised the staff and students by demonstrating his prowess in Cantonese as he related the events during the OSCE exam. It was wonderful, and yes it is a joy and a privilege to teach these students. I have high hopes for them. But a couple of thoughts do cross my mind. One of course is that such a celebration could never happen in the UK. The managers in their infinite wisdom have determined that white coats are a threat to patients. What nonsense! Next they will be declaring that hospitals are going to do away with bed linen as it is a source of infection. Hand washing is what is needed—just look to the work of Ignaz Semmelweis 1818-65. They should include some lectures on the history of healthcare in healthcare management school.

But there was another more pressing and more poignant thought going through my mind and that related to a full page feature in our local English language paper entitled “A Dying Profession.” It was all about doctors and appeared on 28 April 2012 in the South China Morning Post (SCMP). For me the first few sentences were like a fluorescent red rag to a generally phlegmatic ball. I must quote,

“Young doctors are increasingly turning away from the more important fields of medical science to embrace the easier and more lucrative areas of plastic surgery and anaesthesiology.”

It is the practice of the SCMP to append the reporter’s email address to the by line and I had no hesitation in sending a pretty terse email to register my protest. I am old enough and wise enough to know that the majority of journalists are self-respecting professionals, and it is not in their best interests to misinterpret the views of those they interview. So I could not attribute the misconceptions of my specialty to Emily Tsang, the author of the piece.

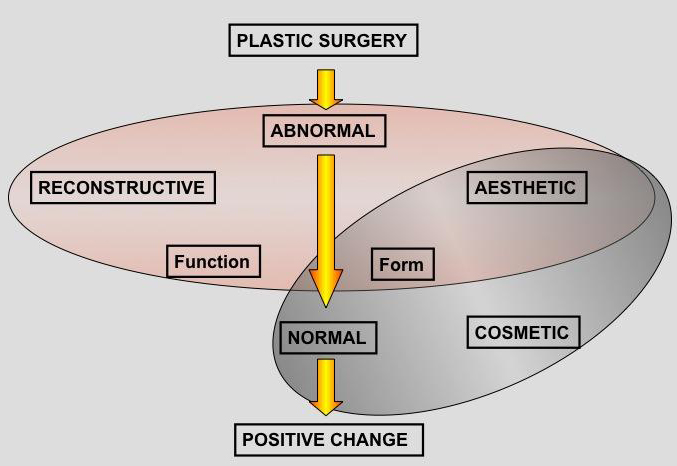

It has been a relentless campaign to explain to the final year medical students what plastic surgery is and what plastic surgeons do. It will require a generational change for this awareness to spread through the medical profession in Hong Kong. I use the Venn diagram (see below) to illustrate the relationship between various terms that are so often confused.

Plastic surgery is the overriding term for a surgical specialty that uses specialised techniques, devices, and strategies to produce a positive change in a person’s form and function. The challenge is then to bring together the vast spectrum of activity that comprise plastic surgery. I show a picture of a coin (unfortunately a Euro, but I am going to change that) and talk about the two faces, one represents reconstructive plastic surgery and the other represents cosmetic plastic surgery and they are united by a common appreciation of aesthetic principles of beauty, shape, and form. So what is the difference between reconstructive plastic surgery and cosmetic plastic surgery? It is where the individual patient journey begins. If they start from a position of abnormality due to trauma, surgical tumour ablation, congenital anomaly and we want to restore form and function towards normality, then this is reconstructive plastic surgery. If, on the other hand, we have a patient who is essentially normal for their sex and age and wants to enhance their appearance surgically then we would call this cosmetic plastic surgery.

The students “get it.” And so do peers and colleagues when you put it in such simple terms. What distresses me though are those who are so insecure in their own image that they need to cloud themselves in an aura of mystery to justify their existence. I am talking now about the plastic surgeons who try to define what and who they are. In this context the greatest confusion is between the terms “aesthetic” and “cosmetic.” I have referred to this confusion before. But the point of this is that it must be a truly misinformed medical professional who can say that plastic surgery is not an important medical specialty. Just look at burns care, for example. We have introduced the concepts of transplantation and immunology to medicine, we are at the forefront of clinical application of tissue engineering, and we have been using clinical cell based therapies for over 30 years and are now at the cutting edge of clinical stem cell applications. Let us also remember who gave a modern ethical framework to medicine. Autonomy? Let these misinformed people spend a few days with a busy plastic surgeon dealing with a major acute burn or planning the reconstruction of a face destroyed in an acid assault attack. Let them sit at our side as we spend hour after hour patiently reconstructing defects left when the onocological surgeons have done their best. Let them join in our world of microsurgery, and let them see if this is easy and undemanding as they think.

Poor Emily, I tracked her down and we talked. I talked. She filled many pages of her notebook and I wonder what “sound bites” she will extract. I did speculate on some of the concerns expressed by senior and respected professors quoted in her article. We live in a changing world; expectations change and I will talk about that on another occasion. In the meantime I can only reflect on the happiness and joy of our wonderful graduating medical students and hope that they prove the cynics wrong. Medicine is not dying. It is evolving, it is exciting, it is relevant, and it remains one of, if not the most, challenging and rewarding of professions.