Mary Assunta

Southeast Asia Tobacco Control Alliance (SEATCA)

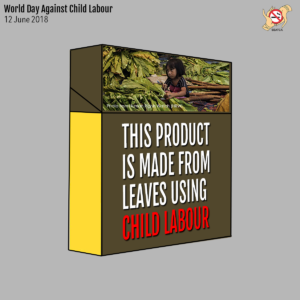

Today is World Day Against Child Labour and this article is dedicated to the millions of children trapped in child labour. It is a reminder that in the 21st century we have failed our children miserably, otherwise there would not be 152 million children working, many full-time.

According to the International Labour Organization (ILO), about 108 million children, or 70% of the children involved in child labour, are concentrated primarily in agriculture. Of these, many millions are believed to be involved in tobacco growing.

The ILO states that in impoverished tobacco growing communities, child labour is rampant and that this problem has increased in some countries where tobacco production has increased. In Malawi for example, whose economy is dependent on tobacco, 63% of children were engaged in child labour. While international agencies acknowledge the problems of child labour in tobacco growing are significant, there are no reliable estimates of the true scale of the problem in the 124 countries where tobacco is cultivated.

Transnational tobacco companies (TTC) and international leaf traders profit from cheap leaves produced in low-income countries using child labour. Japan Tobacco International (JTI) and an industry front group, the ECLT (Eliminating Child Labour in Tobacco Growing) Foundation have given grants of about US$15.4 million to the ILO, ostensibly to address child labour in six tobacco growing countries.

These programmes are part of the TTC’s corporate social responsibility (CSR) programmes and do little to solve the deeply entrenched problems farmers face, which are linked to the industry itself. The WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) calls on Parties to ban such tobacco related CSR activities. The ILO remains the only UN agency still collaborating with the tobacco industry.

Despite increasing pressure to cut ties with the tobacco industry, the Governing Board of the ILO has postponed the decision about whether to do so three times, pushing it back to November this year.

While the ILO remains in limbo on the issue, this June 30 the grant from the ECLT to the ILO will expire. The ECLT’s US$5.3 million was earmarked for activities in Uganda, Malawi and United Republic of Tanzania. The ILO has provided no details on how exactly this money was used in these countries.

Cutting ties with the tobacco industry is inevitable for the ILO. They know they must not renew or extend the contract with the ECLT. Meanwhile the ECLT continues to reap public relations benefits from its ILO association. The ECLT has recently refreshed its website, replete with heart-warming photos of children and communities.

Tobacco industry sponsored programs do little to curb child labour in tobacco farms because they do not improve the tobacco industry-driven cycle of poverty for tobacco farmers, such as low leaf prices and unfair contracts, that forces children into the fields.

Multiple reports have documented that abusive contracting arrangements in countries including Malawi, Bangladesh, and other countries lock tobacco farmers and their families into generational cycles of poverty and indebtedness. According to tobacco industry researchers Otanez and Glantz, the tobacco industry uses ‘greenwashed’ supply chains to make tobacco farming in developing countries appear sustainable while continuing to purchase leaf produced with child labour and high rates of deforestation.

In June 2017, the UN Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) in its resolution E/2017/L.21 encouraged UN agencies to develop policies that would place a firewall between the UN and the tobacco industry. Despite this important resolution, the ILO has failed to make a decision to cut its ties with the industry.

Sustainable Development Goal target 8.7 aims to end the worst forms of child labour by 2025. After almost two decades, and multi-million dollar tobacco industry CSR activities, the problem of child labour in tobacco production remains widespread. The tobacco industry does not have a date on zero-child labour policy and based on the glacial pace of progress, the SDG target will not be met in the next seven years. The ILO must prioritize protecting children over continuing to accept funding from an industry that exploits farmers and their children while producing products that kill. The choice to do so can be postponed no longer.