Dr Lowri Evans (Registrar in Palliative Medicine) , Dr Clea Atkinson (Consultant Palliative Medicine), Professor Anthony Byrne (Consultant Palliative Medicine)

Cardiff and Vale University Health Board and Velindre University NHS Trust, Cardiff, UK

In April 2020, the Palliative Care team at the University Hospital of Wales (UHW) were contacted by the respiratory unit, asking for advice on how best to address end of life symptom control of COVID-19 positive patients. These specific patients were those deteriorating very rapidly (in some instances in less than an hour) towards the end of life, despite maximum appropriate active management, including non-invasive ventilation (NIV). The hospital’s 36-bedded respiratory unit routinely manage acute respiratory cases, also containing a four-bedded high care NIV bay within it, which offers provision of both bi-level positive airway pressure (BiPAP) and continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) non-invasive ventilation to patients in respiratory failure. During the first wave of Covid-19, the ward was converted to primarily provide CPAP ventilation to Covid-19 patients who were not yet requiring intubation for full ventilation on intensive care (ITU), or when ITU level care was not appropriate. This ward team are very experienced in provision of NIV and also the withdrawal of this in the deteriorating COPD patient, who would usually be in Type 2 respiratory failure, with associated hypercapnia causing drowsiness and lessening of awareness at the end of life. In contrast, COVID-19 positive patients were more often developing Type 1 respiratory failure requiring CPAP, and if deteriorating despite this support, patients are much more often alert, leading to a far more challenging end of life situation at the time of NIV discontinuation.

The COVID-19 pandemic has necessitated reacting quickly to emerging new clinical challenges. In this instance a need for intervention was prompted by a cohort of patients deteriorating very rapidly, resulting in sub-optimal symptom control at the end of life. One particular type of situation acted as a trigger for the respiratory team to request a structured plan that could be implemented by a multi-professional team: if a patient deteriorated despite NIV, which was their ceiling of treatment, and a plan was agreed with the patient to discontinue NIV, what would be the best approach. It was clear that distressing situations for patients where air-hunger or a feeling of suffocation ensuing would need to be avoided with evidence-based palliative care approaches.

The Palliative Care team were asked to advise on timings and doses of medications to help better manage symptoms for COVID-19 positive patients approaching the end of life, and specifically those patients having non-invasive ventilatory (NIV) support as their ceiling of treatment, who were deteriorating very rapidly despite this.

NIV does not have to be discontinued for patients in the terminal phase of an illness if this may worsen symptoms1, however it may be the patient’s preference to do so especially in this context owing to COVID-19 infection prevention measures, since patients who wished to have a family member present in serious illness, cannot do so whilst on NIV as this is an aerosol-generating procedure (AGP). Discontinuation of NIV therefore allows these patients to be moved to a non-AGP area where loved ones could then be with them at this distressing time.

Key themes

Following case note review and direct discussion with staff involved in COVID-19 positive patients’ care during discontinuation of NIV, three key themes emerged:

- Patient alertness and awareness:

- Patients were usually in Type 1 respiratory failure.

- Patients were usually alert and aware, despite profound hypoxia and a rapid physiological deterioration.

- Patient alertness was contributing to the distress and fear experienced by not just them, but also family/friends and staff when NIV was discontinued.

- Rapid and acute physiological deterioration:

- The deterioration was often so acute, rapid and unpredictable that even if a syringe driver had been prescribed and initiated, this had insufficient time to take effect.

- Symptoms escalated by discontinuation of NIV:

- Symptoms, especially dyspnoea and agitation were escalating acutely with discontinuation of NIV. This change in symptoms was sudden, distressing and difficult to control.

- In some patients, usual ‘as required’ doses of symptom control medications (e.g. midazolam and morphine 2.5mg PRN subcutaneously) administered following the withdrawal of NIV, appeared insufficiently effective when controlling symptoms and even if repeated frequently

It therefore became clear that a different approach to discontinuation of NIV in the deteriorating COVID-19 patient was necessary. The respiratory team requested clear guidance that could help guide this process across COVID-19 AGP wards delivering NIV, to improve symptom control in these patients in the last phase of life.

Summary of Symptom Control Guidance

A symptom control flowchart was developed and agreed for use in Cardiff and Vale University Health Board (CVUHB) specifically for managing the rapidly deteriorating patient with COVID-19 on NIV as their ceiling of treatment (See Fig 1). This was later formatted and formed part of the All Wales COVID-19 National Secondary Care Guidance website as a palliative care resource 5.

Prior to application of the guidance, a ceiling of treatment for an individual must be clearly defined, including documentation of the decision not to intubate and completion of a DNACPR form, for instance. A clinical multidisciplinary/senior decision to focus on symptom control and end of life care, with involvement of patient if able to, and family/proxy should have been taken. Discussion with the patient and/or family regarding current and future realistic treatments and priorities of care should have taken place. Multidisciplinary teams on relevant wards were encouraged to discuss such scenarios and how they would react as a team to implement the guidance.

The guidance is clear that the goal is to induce sedation to relieve agitation and distress, prior to discontinuation of NIV. The aim is for the least necessary level of sedation, but where there is no response to voice or glabellar tap. Suggested doses to achieve this include initial doses of subcutaneous Morphine 10mg and Midazolam 10mg given subcutaneously. If not adequately sedated 15 minutes after administration of these first doses, further doses of Morphine 5mg and Midazolam 5mg can be given, with the addition of a dose of Levomepromazine 25mg subcutaneously if agitation/distress is severe on clinical assessment. All the above doses can be modified to individual patients, taking into account their renal function, for instance.

The final step is the weaning of NIV once a sufficient level of sedation is achieved. The NIV should be decreased by 50% and if the patient remains comfortable after 10 minutes they should be weaned off the NIV as appropriate. A syringe driver should be considered in addition, depending on the speed of the deterioration, with suggested starting doses of Morphine 15mg, Midazolam 20mg and Levomepromazine 25mg, as it is important to then maintain a degree of adequate symptom control. Repeated prn subcutaneous doses of Morphine 5mg, Midazolam 5mg +/- Levomepromazine 12.5mg can also be used. Yet again, the above doses may have to be lower for some, and higher for others and it is a highly individualised approach.

Figure 1: Locally formatted CVUHB Palliative Care symptom control guidance in rapidly deteriorating patient with COVID-19 on NIV as their ceiling of treatment

Development of the guidance

The guidance was developed following rapid review of existing published guidance for NIV withdrawal and sedation for other comparable clinical situations, with adaptation using the experiential knowledge of the palliative care and respiratory teams in managing COVID-19 positive patients 1,3,4.

A health board-wide consensus was essential to provide consistency and confidence to guide staff at any time of day or night. It was emphasised that this was not a substitute for routine palliative care advice, which all staff are encouraged to access whenever required. It was important that both palliative care and respiratory team members agreed with the proposed guidance, especially ward staff caring for these patients. Those consulted included palliative care specialist multidisciplinary team members, respiratory senior nurses and staff nurses and all hospital Palliative and Respiratory Consultants in Cardiff and Vale University Health Board (CVUHB). Staff fed back that they had found other types of COVID-19 guidance in the form of flowcharts particularly useful in terms of clarity and ease of direction.

The beginning of April saw the highest daily COVID cases in CVUHB with increasing numbers of patients who may have directly benefited from this guidance2. Staff were insistent that future episodes of NIV discontinuation needed to be overseen with better control and this added to the sense of urgency to come to a consensus and provide guidance as soon as possible. The timeline (Fig 2) demonstrates the efficiency of the consultation process and how guidance was so rapidly produced. Had this not been taking place during a pandemic, this process would very likely have occurred at a much slower rate. Teams motivated by patient dignity and wellbeing brought a sense of urgency and cohesion to work rapidly towards developing this guidance and to quickly ensure approval for use both locally and nationally.

Figure 2: Timeline of guideline development April 2020

Feedback and evaluation of guidance

The initial informal feedback from staff once using the guideline was positive, but to better evaluate this an online survey was distributed in July 2020 to respiratory consultants, junior doctors, and nursing staff from the respiratory team. The survey produced 12 responses in total, 8/12 were from nursing staff and 4/12 were from medical staff. The survey was distributed to consultants via e-mail with 3/9 (33%) consultant response rate. The survey was distributed to junior doctors and nursing staff via closed work social media groups within the respiratory team with 8/61 responding (13%) and one junior doctor response. There may be several reasons for the low response rate, including ‘questionnaire fatigue’ after the first wave of Covid-19, or because some respondents may not have had direct experience of using the guideline, since all staff from Band 2 and above were included to ensure no-one was missed. It was felt to be important that all ward staff in contact with these patients be given the opportunity to comment, since we were keen to capture any disagreement or discomfort with this management approach.

A third of respondents had cared for more than ten COVID-19 positive patients who required discontinuation of NIV, and although this is a small sample, the qualitative and quantitative data is helpful in understanding how the guideline has been initially received by the respiratory staff and indirectly gives some evaluation of the pathway effectiveness. It has also provided an opportunity to anonymously raise any concerns or suggested improvements to the guideline. The aim of this evaluation was to review the guideline in advance of a possible second peak of COVID-19.

Before the introduction of the guideline only 17% of staff felt these patients’ symptoms were adequately controlled. They described the clinical situation with phrases such as: “Patients were too awake and aware of the situation. Withdrawal [of NIV] distressing for patients, staff and family” and “Having patients who were awake and completely aware of their prognosis and demise was the hardest thing I’ve ever had to witness”. These comments echo the distressing experiences which had led to the Palliative Care team being approached to develop this guidance.

Following introduction of the guideline the number of respondents who felt symptoms were adequately controlled rose from 17% to 58%, however 25% of respondents were unsure that there was improvement and 17% felt that symptoms remained uncontrolled. Comments regarding this included “patients were much less air hungry, less distressed” and “I feel any anxiety and pain was addressed”. However some felt that patient symptoms were better controlled but “emotional issues remain”.

Staff were also asked to rate the value of the guideline for managing discontinuation of NIV in the deteriorating COVID-19 positive patient, using a Likert scale between 0-10 (0 = not at all valuable, 10 = extremely valuable). Responses ranged from 5 to 10 with both the median and mean rating being 8, suggesting that having the guideline was a useful way to support staff managing these patients.

It is also recognised that discontinuation of NIV is potentially distressing for staff regardless of how well symptoms may be controlled, however staff distress appeared to be eased somewhat by having the support of the guideline, with the mean distress score (where 0 = not at all distressing and 10 = extremely distressing) falling from 8 to 5 after the introduction of the guideline. “Guideline was a positive intervention but overall still a difficult process – especially for the nursing staff”.

Feeling supported and the availability of specialist palliative care advice was highlighted by staff as being key to help them manage these distressing situations better. “Even though it was still distressing the guidelines were invaluable and your support was hugely appreciated”

The doses of medications suggested in the guideline may be unfamiliar to staff outside of the specialist palliative care setting. Explanation of why these medications were used for symptom control was important. A video tutorial was produced to explain and educate that these medications were appropriate and proportionate in this specific clinical situation to achieve the goal of care and this is available on the All Wales COVID-19 National Secondary Care Guidance website. However, local support from the Palliative Care team to answer questions and to address fears and uncertainties is important to ensure that staff are comfortable with the rationale, the approach and the medication dosing.

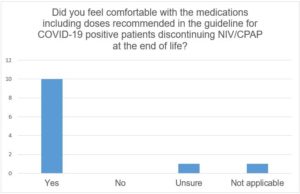

Figure 3 demonstrates that this was effective and that the majority of staff felt comfortable with the medication doses in the guideline.

Figure 3: Graph demonstrating staff responses regarding whether they felt comfortable with the medications, including doses, recommended in the guidance for COVID-19 positive patients discontinuing NIV at the end of life.

There can sometimes be concern that guidelines result in a formulaic and less individualised approach to managing a patient in the last phase of life. However this must be balanced with providing non-palliative staff with the appropriate information and guidance to enable them to care for all patients in a timely and responsive way. This flowchart appears to be an effective intervention in our health board to better manage COVID-19 positive patients who have very serious illness and are deteriorating rapidly. It also ensured a higher likelihood of being able to offer patient choice, especially for those who requested not to remain on NIV. We were also glad to hear that staff felt that despite the difficult circumstances, patients were treated with compassion: “I feel all patients were treated as individuals, with dignity and respect. Each patient has their own wishes and as staff we adhered to this.”

Summary

The COVID-19 pandemic has been described as an ‘unprecedented palliative care emergency’ resulting in large numbers of patients deteriorating rapidly in acute settings. Palliative medicine has a responsibility to support colleagues to best manage these patients. Key to the appropriate implementation of this guidance has been the support of the local palliative care team and good working relationships between the palliative and respiratory teams. A collaborative approach facilitated the rapid development of guidance in response to a direct patient need. Implementation of this flowchart has given the respiratory team some guidance to support better end of life care and to reduce distress for patients, families and staff. We will be continuing to evaluate its effectiveness during the next wave of the Covid-19 pandemic.

References

- Faull C. Withdrawal of ventilation at the request of a patient with motor neurone disease: guidance for professionals. Association for Palliative Medicine of Great Britain and Ireland. 2015.

- Public Health Wales. Rapid COVID-19 Surveillance. Confirmed Cases by Sample Date: Cardiff and Vale UHB. 2020. https://public.tableau.com/profile/public.health.wales.health.protection#!/vizhome/RapidCOVID-19virology-Public/Headlinesummary (accessed 20 Sept 2020).

- Davidson AC, Banham S, Elliott M, et al. BTS/ICS guideline for the ventilatory management of acute hypercapnic respiratory failure in adults. 2016; 71 (Suppl 2):ii1-35

- Grounds M, et al. Intensive Care Society Review of Best Practice for Analgesia and Sedation in the Critical Care. 2014.

- NHS Wales. COVID-19 Palliative Care Guideline when CPAP/ NIV is the Ceiling of Treatment. All Wales COVID-19 Secondary Care Management Guideline.https://covid-19hospitalguideline.wales.nhs.uk/education/managing-rapidly-deteriorating-patients-with-covid-19-when-cpap-niv-is-their-ceiling-of-care/ (accessed 02 Sept 2020)