During the COVID-19 pandemic, the National Health Service (NHS) in England rapidly created the NHS Nightingale Hospital London (‘the Nightingale’) – a field hospital providing additional clinical capacity to support the NHS. This unique clinical environment presented both familiar and new, complex challenges in ensuring safe use of medicines. As part of the creation of the Nightingale, novel Bedside Learning Coordinators (BLC) were deployed to gather experience-based insights from front-line staff, as outlined by Shand et al.1 Here, we describe more specifically how BLCs were applied as part of a learning system across two phases of the Nightingale to make rapid, significant improvements to medication safety, and how this approach can be applied to routine NHS care in the future.

Medication safety is a key priority on healthcare agendas nationally and locally.2-4 According to the World Health Organization, unsafe medication practices and the medication errors that may result from them are the leading cause of avoidable harm, with an estimated US$ 42 billion spent globally in litigation costs, increased length of stay and complications.2 Improvements in medication safety require consideration of the complex factors involved in the entire cycle of prescribing, dispensing and administering medicines.5 Adopting a systems approach to medication safety, also known as the human factors approach, focuses on the role of the system in errors, rather than on individual fallibilities.

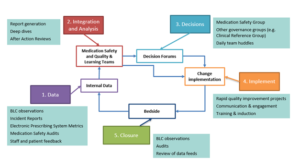

Key to learning how to make systems safer is the availability of data, to understand where improvements are needed. A learning system model6 was embedded across both phases of the Nightingale and used to sense and respond to medication safety issues (Figure 1). BLCs collated daily information from observations and discussions on the wards relating to wellbeing, workflows, processes, staffing and patient safety, including medication safety, as described by Shand et al. The BLC team used these data together with the multidisciplinary team to support a learning cycle of improvements, communication and audit. Collaboration between the BLC and pharmacy teams within the Nightingale was key to driving forward improvements in medication safety.

Figure 1: Learning System for Medication Safety at the Nightingale

Nightingale Phase 1: Establishing the Learning System

When the Nightingale first opened in March 2020 during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, the clinical model focused on critical care to ventilated patients with COVID-19. There were clear challenges for maintaining medication safety in this new environment. Staff were redeployed from different NHS organisations to work in an unfamiliar, high-pressure environment and within newly formed teams. Many were new to critical care, with minimal experience of critical care medications. The use of personal protective equipment made communication and identification of staff members difficult. In addition, there was uncertainty over the optimal management of COVID-19, with rapidly evolving evidence and clinical guidelines under continuous modification. Design of the safety system was therefore in place from the start, with the use of a pre-printed drug chart with standard medication protocols, and pre-filled syringes to aid administration. However, medicine mis-selection and lack of familiarity in use of these medications remained a concern.

Senior pharmacy team members therefore joined the BLC team, undertaking shifts dedicated to observation of the bedside workflows and conversations with frontline staff. These were six-hour shifts at different times of the day, designed to capture insights from day teams, night teams and handovers using a standardised data capture form. These insights were fed back to the quality and learning team (Figure 1) to triage into action, ultimately categorised as ‘fix’, ‘improve’ or ‘change’ in practice1.

Pharmacy input to these multidisciplinary BLC shifts shone additional light on medication-related issues. For example, feedback from one BLC shift led to review of the crash trolley contents, relocation of specific medicines and oxygen cylinders to facilitate better access, and staff education on use of drug syringe stickers. It also highlighted risks related to mis-selection of similar-looking syringes and an incident involving insulin misadministration. Additionally, following any medication-related incidents, the pharmacy team held learning events that combined an after-accident-review approach with clinical teaching and an action plan focused on system-level improvements.

In addition to this team response, a multidisciplinary Medication Safety Governance Group was convened at an organisational level to support action plans mitigating medication safety risks. Rapid changes were facilitated by the group, including use of coloured drug syringe stickers, new insulin guidelines, and revised drug chart design. In addition, a streamlined process was introduced to sign-off medication-related guidelines and standard operating procedures for the Nightingale. Finally, as the Nightingale went into hibernation in May 2020, the systems approach to medication safety and the lessons learnt were carefully documented.

Nightingale Phase 2: Adapting to a New Care Model

When the Nightingale reopened in the second phase of the pandemic in January 2021, the clinical model had shifted significantly. It was now a community hospital model providing support with general rehabilitation and discharge post COVID-19 and for other conditions, in order to increase acute hospital bed capacity for people with COVID-19. As a result, the medication safety requirements also shifted. There was no administration of intravenous drugs within Nightingale 2, but instead a focus on optimising a broader range of long-term medications that were administered by nursing staff in daily drug rounds. Instead of paper drug charts, an electronic prescribing system was in place. However, the challenges of a mixed staff group and unfamiliar environments and protocols remained.

The learning system approach was carried forward into Nightingale 2, with the BLCs working with the pharmacy and medication safety team to rapidly collect insights about medication-related incidents. In traditional error management, patient safety issues are often identified retrospectively following an incident. However, the BLC role and use of an ImproveWell app to log issues and observations allowed a continuous ‘temperature check’ of the ward, staff and potential issues arising. The app was a new initiative for Nightingale 2 that enabled all staff to engage in real-time quality improvement feedback and idea generation. While medication safety specific concerns only accounted for 6% of all logged items (10/154 incidents) on the Improvewell app, they were combined with a pharmacy quality & safety walkaround exercise to shape a proactive medication safety plan. Quick wins included reorganisation and labelling of medication and oxygen storage areas, streamlined medication ordering processes, introduction of a pharmacy technician checklist and a revised pharmacy induction for healthcare staff on their first day.

Progress was monitored with the introduction of a fortnightly Medication Safety and Management audit, alongside continuous review of BLC data and incident reports. The pharmacy team also worked with the electronic prescribing and medicines administration system team to develop metrics on delayed doses and dose omissions. Again, a multidisciplinary Medication Safety Group was formed to review these data feeds and support action plans. This learning system achieved rapid and measurable improvements in medication safety during this Phase.

Taking the Approach Forward into Routine NHS Care

As the host organisation for Nightingale 2, North East London NHS Foundation Trust (NELFT) has embraced the opportunity to transfer the learning approach to their core services. The Medication Safety Team has been motivated to change current practice from what seemed more like an assurance function, comprising review of medication-related incident reports at quarterly meetings. Instead, local Medication Safety and Quality Huddles are being introduced, each representing a directorate within NELFT and meeting monthly. Each huddle will have a small multi-disciplinary membership comprising clinicians and managers with the skills, resources and desire to forge data-driven improvements within their services. Trust-wide assurance will be provided via a summary report to the overarching NELFT Medicines Optimisation Group.

We are very early in this journey and aware of changes necessary to adapt to this new context. These include adapting the language of “bedside” to a diverse community service and balancing competing priorities and resources required to operate multiple forums. However, it is anticipated that a more proactive learning system approach closer to front-line services will save time by addressing issues prospectively rather than responding to reported incidents. At the same time, robust communication channels among the groups will be required to avoid duplication and enable shared learning across the different directorates. As a successful example of this new strategy, this approach already has been applied to the four COVID-19 vaccination centres NELFT are operating.

Conclusion

Application of a learning system approach can facilitate rapid and significant improvements in medication safety by ensuring that observations from frontline care are translated into rapid fixes and improvements in the system and a proactive governance response. The use of multiple data feeds to inform a learning cycle for medication safety was successfully employed across different clinical models in the Nightingale and can be successfully adapted to routine NHS care.

–Sonali Sanghvi, Dr. Samantha Machen, & Rahul Singal: all worked at the Nightingale during the COVID-19 pandemic and wrote this blog on behalf of the Nightingale Pharmacy and Bedside Learning Coordinator teams.

Sonali Sanghvi is Pharmacy Advisor in the Genomics Unit at NHS England and NHS Improvement. She previously led on formulary and medicines governance at UCLH NHS Foundation Trust and is interested in quality improvement, value-based care and genomics.

Dr. Samantha Machen (@samantha_machen) is an Improvement Facilitator at Central London Community NHS Trust and has a PhD in applied health research from UCL. Her key research interests include the governance and improvement of patient safety, safety culture, and quality improvement.

Rahul Singal is Chief Pharmacist at North East London NHS Foundation Trust. Prior to that he has held senior leadership roles at Kings College NHS Foundation Trust and NHS England. He has a professional interest in improvement and clinical leadership.

References:

1. Shand, J., et al., Systematically capturing and acting on insights from front-line staff: the ‘Bedside Learning Coordinator’. BMJ Quality & Safety, 2021: p. bmjqs-2020-011966.

2. World Health Organisation, Medication Without Harm- WHO Global Patient Safety Challenge. 2017.

3. European Medicines Agency, Good practice guide on recording, coding, reporting and assessment of medication errors 2015.

4. Elliott, R., et al., Prevalence and Economic Burden of Medication Errors in The NHS in England. Rapid evidence synthesis and economic analysis of the prevalence and burden of medication error in the UK. 2018.

5. Dean Franklin, B. and M.P. Tully, Introduction, in Safety in Medication Use B. Dean Franklin and M.P. Tully, Editors. 2015, CRC Press: London

6. Bohmer, R., et al., Learning Systems: Managing Uncertainty in the New Normal of Covid-19. Nejm Catalyst Innovations in Care Delivery, 2020: p. 10.1056/CAT.20.0318.