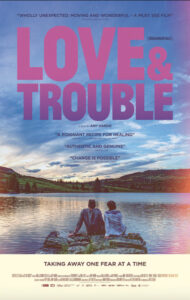

Love and Trouble (Amy Hardie, UK, 2024), premiered in Dokumentale Film Festival, Berlin October 2024.

Review by Robert Abrams, Emeritus Professor, Weill Cornell Medicine, New York.

Love and Trouble, a documentary film, portrays Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) as it affects two protagonists: Kenneth, after repeated wartime experiences in combat; and Kerry, after an emotionally scarring incident of sexual abuse in childhood. Using their real-life stories in a contemporaneous sequence, the film offers a moving revelation of traumatic occurrences and the extended process of healing them. While earnest and genuine, the two principal characters, a married couple, are both remarkably adroit, raising a question about the generalizability of their paths to healing. But that possibility does not detract from the value and importance of this film.

Kerry Preston Watson was a vulnerable young woman who had been psychologically damaged early in life. Her father was imprisoned for armed robbery when she was an infant, and she had little contact with him. Her mother was a single parent, stressed and impoverished. One assumes that loving and sustained parental relationships were insufficient or lacking. Then, Kerry had been raped at the age of nine, leaving her with an aftermath of shame and guilt.

Miserable, Kerry made a hapless suicide attempt at the age of 12. She became a rebellious, unhappy adolescent who dropped out of school at 15. By age 18 Kerry was desperate to leave the restrictions of her hometown. She chose for her escape destination the city farthest from home that she could reach with 5 pounds in her pocket. There she worked as a dancer in a bar, a patently unwise choice given her childhood experience, puzzling except as a self-punitive attempt at expiation of her misperceived guilt. For a while the lights and music obscured her consciousness of the leering men who watched her perform. But one day she broke down, overcome by memories of having been abused. It was at that point in her life that she met Kenneth Watson.

Kenneth was a soldier who had joined the army at the age of 16. Sent to Afghanistan in 2011, he advanced to patrol commander and sniper, the man who delivers lethal payload to the enemy. Kenneth also took on the responsibility of keeping the soldiers around him alive.

When they met in 2012, Kerry was drawn to Kenneth for his kind and gentle manner. But Kenneth, fearing that she would turn away from a person who had been immersed in wartime killing, had not told Kerry about his ordeals in Afghanistan; nor had he described the scenes of children being used as human shields, or the anguish of mortally wounded soldiers.

Not long after the couple’s wedding, at the funeral of a soldier who had been killed in battle under his command, Kenneth felt so tormented by guilt that he could not bring himself to say even a few words of comfort to the young man’s grieving mother.

Subsequently, Kerry observes Kenneth’s sudden withdrawal at a fireworks celebration. This moment marks the beginning of his descent into the darkness of night terrors, paranoia and an ominous loss of control. Kenneth attempts or contemplates suicide on 6 occasions during this period, while Kerry removes knives and other sharp items from the house. She justifiably begins to fear for the safety of their infant son, Harris. She also considers divorce or arranging for Kenneth to be remanded to a psychiatric institution. But she concludes that she cannot not assure her own safety and that of her son by abandoning a person she deeply loves because of a mental condition for which he is blameless.

Determined to find therapeutic opportunities for Kenneth, a resourceful Kerry discovers several. Kenneth begins with a behavioral therapy program featuring encounters with retired racehorses. These horses, once high-level performers, have become skittish, agitated, and financially worthless, all aspects relevant to Kenneth’s own circumstances. Trying other approaches, Kenneth finds that therapies involving introspection are decidedly “against the grain.” His military training as a combat sniper had conditioned him to depersonalize, to “feel nothing but the recoil on my shoulder,” and when the task required it, to turn away from the screams of the dying.

While watching over Kenneth’s halting progress, Kerry addresses her own life goals, now becoming a university student. At this point, however, there is an unevenness in the couple’s rehabilitation as individuals, with Kerry’s personal growth in the ascendant and Kenneth still struggling and beginning to resent Kerry’s competence and initiative. But they come to use these disparities as a bolster for their marriage, whereby each partner alternately encourages the other.

Kerry meanwhile graduates with a degree in psychology, and with great satisfaction opens a practice of social work psychotherapy. Kenneth’s outlook eventually improves sufficiently to warrant his own training as a lay counselor; and he at last connects with Harris, the son he had never stopped loving but with whom his symptoms had inhibited him from freely expressing affection.

After a decade of marriage, Kerry and Kenneth emerge with a gratifying sense of achievement. A few relapses, mainly Kenneth’s, have been shown, but otherwise viewers’ expectations of their ultimate success remain unbroken. This positive anticipation recalls the question posed earlier, whether Kenneth and Kerry, as exemplars, are inadvertently creating the impression that resolution of post-traumatic symptoms is as likely or possible for everyone as it has been for them.

But that is not actually a point at issue in this arresting film. Kerry and Kenneth are exceptional. As a married couple they have the advantage of being able to observe and encourage each other. Separately, each partner is guided by social conscience and gifted with the ability to love unselfishly. Allowing their lives and struggles to be the subject of a film shared with a public audience is itself an act of generosity and sublimation, transforming personal misfortune into a larger public good.

So, it is fitting that Kerry and Kenneth, and others like them, should be the ones to open their hearts and offer their experiences to those who may not necessarily succeed in moving beyond trauma as thoroughly as they have done themselves.