Blog by Sloka Iyengar, PhD

The intentions and motivations of scientists are still misunderstood by the public. The reasons for this disconnect are complex and include scientific jargon, the third person orientation of science, and the stereotype that scientists are socially inept and isolated. However, the “doing” of science is a group process involving not only university professors and students, but important support staff such as funding agencies, administrators, as well as cleaning and janitorial services. While there are efforts to popularize science, many challenges exist: lack of funding and sustained interest, lack of support from institutions, and shortage of time and resources. Also, science popularization efforts tend to focus on specific scientific subfields, and not on scientific activity in general.

The arts have also been used to popularize science, though the common stereotype that art and science are different human realms has perhaps made these collaborations a fringe activity. Thankfully, productive collaborations between artists and scientists are growing. For example, Dance Your PhD helps scientists connect with movement and dance, infusing their personalities into science. Programs like this encourage scientists to talk about the human aspects of their work without fear of being judged as non-objective and unscientific. Among non-scientists, the description of the sciences as a humanistic endeavor could help make science relatable. My experiences as a practitioner of neuroscience and of a traditional form of Indian dance known as Bharatanatyam have helped me to communicate science to a variety of audiences. Here, I give four examples of how I have done this, after briefly discussing my background in both fields.

Personal Perspective

I am both a neuroscientist and a dancer, but my dance background goes back further than my scientific training. I started learning Bharatanatyam, a 2,000-year-old Indian dance form, at the age of five in Ahmedabad, India. Bharatanatyam incorporates symbolism, philosophy, movement, music, mythology, rhythm, emotion, and storytelling, and it deals with issues that are universal and contemporary. The essence of Bharatanatyam is communication. With proper framing, the dance can travel successfully outside its cultural context—it is suitable for anyone, whether or not they have a connection with Indian culture.

I employ the communicative aspect of the dance in my work with older adults, where I use Bharatanatyam to offer safe and imaginative ways of movement to foster self-expression.1 I continue to learn Bharatanatyam from my gurus in India, and I supplement ongoing training in Bharatanatyam with folk dance, pedagogy, Carnatic music, and Sanskrit. My area of study in neuroscience is epilepsy, and for my doctoral and post-doctoral training, I studied the neural pathways that contribute to the generation and propagation of seizures in temporal lobe epilepsy.2 My recent work brings my knowledge of science and dance together: I have started describing the neural pathways involved in the practice and appreciation of Bharatanatyam.3

Communicating Scientific Concepts through Bharatanatyam

Example 1: Understanding the Brain through Dance

Through an online forum called Vichaar (Sanskrit for “thought” or “contemplation”), I explore several topics related to the arts and the sciences. At a recent recital, I demonstrated how Bharatanatyam could help us understand the ways ours brains process and perceive movement, symbols, emotions, music, and rhythm. Through Vichaar, I also talk about the ways my dance training makes me a better scientist, helping me communicate ideas clearly and appreciate the beauty in science. My science training makes me a better artist as well because it facilitates depth, creativity within a framework, and finding the essence of my practice.

Example 2: Showing Caregiving through Dance and Science

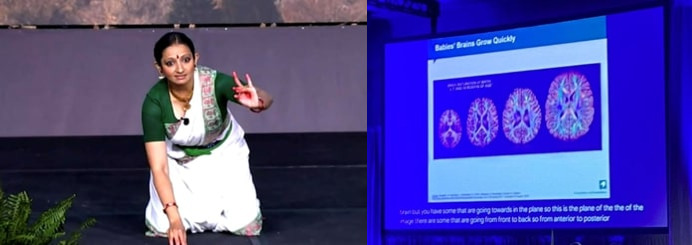

As part of an organization called Parents as Teachers, in 2022 I was invited to a conference to talk about caregiving to an audience of professional caregivers. I described the neuroscience of caregiving and supplemented the science with lullabies and Bharatanatyam pieces expressing the stages of a child as it is being nurtured by its loving and attentive caregivers (Figure 1). Through dance, I showed tangible acts of nurturing (feeding, playing, ensuring physical contact, singing, reading) and connected them with the “parenting network” that enables a caregiver’s response to a child (e.g. recognizing the child’s signals, expressing positive affect, mirroring, and embodying resourcefulness while handling distress). Anecdotally, several people from the audience shared with me that presenting the science and the dance together validated their work, which is so often ignored, and made them feel seen. We are all here because someone took care of us.

Example 3: Creatures on the Move

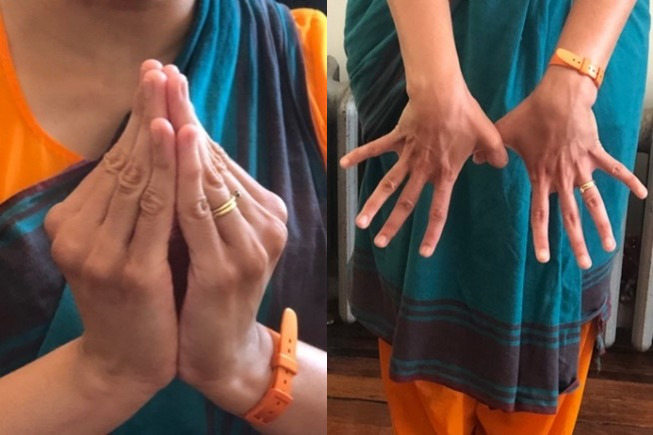

Bharatanatyam has many representations of animals, and through articles in “Creatures on the Move,” I recreate their movements (Figure 2) and discuss how animal brains make such unique movements possible. I have also linked this with my work teaching evolution at the American Museum of Natural History and at St. Joseph’s University, where I discuss diversity, grandeur, and the magnificence of natural variation.

Example 4: Learning and Teaching

At the STEMPeers conference held in Philadelphia in 2022I presented a piece called “The Dance and Music of Neurons” where I elaborated on neuroscientist Vikram Gadagkar’s work studying error detection in songbirds. He shows that the brain switches between “practice” and “performance” modes, similar to human performers (while practicing, I can stop and correct a mistake; while performing, I cannot). I extrapolated from his talk and shared how detecting and addressing errors are important parts of learning a skill. I also explored the long-term journeys of artists and scientists, as both groups acquire skills and knowledge and eventually teach students, sharing common professional and practical trajectories.

Using Bharatanatyam and other traditional art forms to communicate science has many benefits, including science literacy and greater public engagement with science. The synergy established between art and science can also lead to an appreciation of the beauty in the doing and thinking of science. Finally, such cultural enrichment may increase funding for science, as greater engagement leads to greater public understanding and support.

Sloka Iyengar, PhD is a neuroscientist and dancer passionate about relieving suffering through the sciences and the arts. She is developing a program to use Bharatanatyam for creative aging and regularly stages productions that explore the intersections between the arts and neuroscience. More about Sloka’s work can be found here: https://www.slokaiyengar.net/

References

1 Sloka S. Iyengar, “Bharatanatyam in Creative Aging,” Medical Humanities (blog), March 7, 2023, https://blogs.bmj.com/medical-humanities/2023/03/07/bharatanatyam-in-creative-aging/.

2 Sloka S. Iyengar and David D. Mott, “Neuregulin Blocks Synaptic Strengthening after Epileptiform Activity in the Rat Hippocampus,” Brain Research 1208 (2008): 67–73, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2008.02.045.

3 Sloka Iyengar et al., “Reflections on Bharatanatyam and Neuroscience. A Dance Studies Perspective,” International Review of Social Research 11, no. 1 (2021): 288–97, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.expneurol.2014.11.009.