‘Mandoob’ (The Night Courier), Ali Kalthami, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 2023

In UK cinemas from Friday 30th August 2024

Review by Khalid Ali, Film and Media Correspondent

Empathy is a desirable quality in all healthcare professionals. In a seminal article Decety argues that educationalists and learners should start by approaching the sometimes-amorphous concept of ‘empathy’ in a tangible, relatable way to promote its practical applications in medicine. Using an architectural approach, Decety describes nine functional components of empathy based on an affective, cognitive, motivational and regulation framework.1 In this article, I will describe how as a viewer and a clinician, I empathised with Fahad, the central protagonist in ‘The Night Courier’. I will follow that by analysing five elements of empathy using Decety’s model (table 1).

Set in Riyadh, Fahad (Mohammed Aldokhei) is a man in his thirties suffering from generalised anxiety disorder (GAD). After a heated argument with his boss Abu Saud (Mohammed Algarawi), Fahad is fired from his job as a phone operator in a customer service call centre. He is expecting a court sentence for assaulting his boss and vandalising the workplace. Fahad is the principal breadwinner for his family, including Nasser (Mohammed Alttowayan), his frail father who is awaiting a kidney transplant; a recently divorced sister Sarah (Hajar Alshaammari); and Sarah’s daughter Yassam (Amani Alsami). To make ends meet, Fahad takes a low-level job as a courier for a delivery company. A chance encounter brings him face to face with an illegal alcohol bootlegger. After stealing alcohol from the bootlegging gang’s secret factory, Fahad starts selling it to wealthy customers to earn much-needed cash. As a devout Muslim, Fahad is guilt-stricken for having become an alcohol dealer. To make matters worse, Fahad injures a member of the gang in an auto accident. Fearful of a prison sentence, he panics and flees the scene. In a matter of days, Fahad has lost his job, his social status and his moral compass. His fragile mental state is tested to the limit by relentless stress, worry and insomnia.

Ali Kalthami (film writer and director) and Mohammed Algarawi (film writer and actor) explain how they intentionally presented Fahad’s family background and his fragile mental state in a way that would ensure that the audience emphasises with him. Consultant psychiatrist Dr Yahya Al-Hussein provided guidance on how to realistically depict the clinical features of Fahad’s GAD.

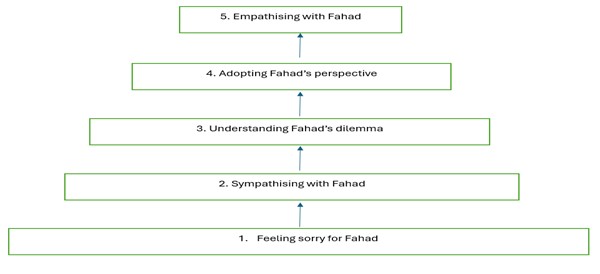

As a viewer, I experienced five emotions in a sequential manner as seen in figure 1 (the pyramid of empathy). From the first scene, I feared for Fahad as he was trapped in his boss’s office and ordered to resign. I then sympathised with him as a diligent son who lovingly bathed, dressed and fed his ailing father. His kind, accepting attitude toward Sarah as she travelled around the city to pitch her naïve ‘ice-cream business’ emphasised his status as a loving brother. Portraying Fahad as a three-dimensional caring human being is a testament to the skill of the film writers and director, complemented by an elegant, yet restrained and nuanced performance by Mohammed Aldokhei. Fahad’s disappointment when abandoned by his female colleague Maha (Sarah Taibah) is captured over the course of a phone conversation by a sudden shift from his normally calm facial expression to one of anger, outrage and ridicule. Appreciating Fahad’s background as a Muslim contributes another important layer to the viewer’s emotional attachment to him and to the understanding of his motivations. Fahad rushes to the mosque to pray, flooded in tears after he accidentally hits the gang member. His praying alone in the big mosque in the early hours of the morning draws attention to his loneliness and social isolation. These expertly crafted scenes echo the feelings of remorse of Rodion Raskolnikov, the protagonist in Fyodor Dostoevsky’s timeless classic ‘Crime and Punishment’. Trying to understand and sympathise with Fahad’s mental anguish and moral dilemma at a rational cognitive level is soon followed by a deeper level of emotional empathy.

Table 1 summarises five functional components of empathy (modified from Decety’s model).2

| Functional component

|

Definition |

| Personal distress | Emotional reaction such as worry, or anxiety experienced after observing another person’s situation.

|

| Empathetic concern (or compassion or sympathy)

|

Feelings of warmth and concern towards another person, and a motivation to improve their well-being

|

| Emotion regulation

|

Spontaneous reactions to someone else’s situation acknowledging their social circumstances while being non-judgemental

|

| Cognitive empathy

|

Imagining or adopting someone else’s perspective to better understand their experience

|

| Emotional empathy

|

Phenomenon when individuals express and feel emotions similar to those of others

|

While it is challenging to quantify the role of medical humanities in improving empathy in medical students,3 films such as ‘The Night Courier’ serve as a fine example of conceptualising empathy for healthcare professionals. Representing the sights and sounds of Riyadh, the film’s visual and sound aesthetics poignantly frame Fahad’s tragic demise. While billed as a thriller drama, the film can also be viewed as a film noir, a black comedy or a character study. Whatever genre it belongs to, ‘Mandoob’ is a must-see for film lovers and humanities scholars alike.

References

[1] Decety J. Empathy in Medicine: What it is, and how much we really need it. The American Journal of Medicine 2020; 133: 561-66.

[2] Decety J. Empathy in Medicine: What it is, and how much we really need it. The American Journal of Medicine 2020; 133: 561-66.

[3] Zhang X, Pang HF, Duan Z. Educational efficacy of medical humanities in empathy of medical students and healthcare professionals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med Educ. 2023 Dec 6;23(1):925. doi: 10.1186/s12909-023-04932-8. PMID: 38057775; PMCID: PMC10698992.