Drew Leder, The Healing Body: Creative Responses to Illness, Aging, and Affliction (Northwestern University Press, 2023, 240 pp. ISBN-13: 978-0810146389).

Book Review by Matthew Swanson

Too often, medical care is offered and experienced as a form of expert technical intervention. Doctors perceive the patient in the role of a passive recipient, and we comply. Dr. Drew Leder, a doctor of medicine and professor of philosophy, seeks a more holistic conception of healing. His newest book, The Healing Body, calls attention to the interactive and symbiotic structures of the patient/practitioner relationship and attends to the subtleties of this dynamic, providing rich insight and new directions for future care.

The Healing Body is the third installment in a trilogy of books written by Dr. Leder that examine the issue of embodiment from a phenomenological perspective, the other two being The Distressed Body (University of Chicago, 2016) and The Absent Body (University of Chicago, 1990). Dr. Leder’s unique combination of medical and philosophical training positions him to provide insight into aspects of patients’ experience of illness, aging, and affliction that otherwise might elude traditional medical models of care and treatment.

Leder’s Chessboard of Healing

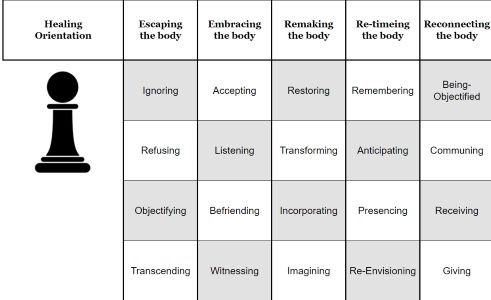

In his introduction to the book, Leader presents a “chessboard” (fig. 1) of possible moves to help readers respond to illness, which becomes an essential analogy and tool for the healing process.

“Twenty Healing Strategies,” (part 1) breaks down the five experiential modalities figured in the chessboard: escaping the body (ignoring, refusing, objectifying, transcending); embracing the body (accepting, listening, befriending, witnessing); remaking the body (restoring, transforming, incorporating, imagining); reconnecting the body (being-objectified, communing, receiving, giving); and re-timeing the body (remembering, anticipating, presencing, re-envisioning). Throughout, the intention is to provide both patients and practitioners with an array of flexible resources for meeting the challenges patients face on a daily basis. The strategies are not arranged in a hierarchy or ranked vis-à-vis one another, but are rather grouped according to the features of lived embodiment that typically characterize them.

For example, sometimes one experiences that “I am” my body; when healthy, the body’s powers of movement and expression simply seem to belong to oneself. At other times, the body stands forth as an object “I have”; during serious illness, it can feel alien and undermining. Such ambiguity in the lived body’s status allows for varying moves on the chessboard of healing. One can distance oneself from the ill body “I have,” for example, by ignoring physical dysfunction, objectifying it, or finding ways to transcend it through intellect or spirit. Conversely, one can move toward the body “I am” by listening more closely to its messages concerning what will lessen symptoms and assist recovery. Again, Leder does not indicate that certain moves are superior to others, simply that it helps to know which strategies one is employing, their strengths and weaknesses, and the other options one has (via the chessboard of healing metaphor). The result is an easily accessible guide that can be effectively employed in a clinical setting or utilized independently by patients.

Humanizing Patient Experiences through Phenomenology

Next, Leder explores the applicability of each experiential modality in depth, taking into account a wide range of patient diagnoses, temperaments, life circumstances, and changing daily conditions. Perhaps the primary strength of this phenomenological approach is its humanizing attention to the direct experience of patients undergoing serious life challenges. Although each modality is initially presented in relation to the philosophical/phenomenological tradition, with an emphasis on the work of major phenomenological figures (Husserl, Merleau-Ponty, Heidegger, Strauss, Ihde, Casey), Leder’s development of these ideas creates a profound synthesis, not a dry philosophical discussion. To illustrate his points, Leder incorporates insights from his own experiences using these strategies as well as the insights of friends, colleagues and acquaintances, which further contextualizes and personalizes his writing.

Someone with walking difficulties due to multiple sclerosis might undergo physical therapy to reclaim previous functioning, an approach Leder calls restoring. Restoring actualizes in the future one’s past mobility. Alternatively, such an individual might alter their gait and environment to accommodate new and perhaps irreversible limitations, a strategy of transforming bodily usage. This also might involve what Leder calls incorporating an external technology into one’s bodily schema (a walker or wheelchair), such that one recovers, even extends, one’s powers of movement. After exploring the particular strengths of each strategy, Leder also considers their “shadow sides,” which he explores throughout the book. (For example, one might become dependent on a wheelchair such that one’s ability to walk unassisted atrophies.) He encourages both patient and practitioner to apply the strategies using practical wisdom, attending closely to how they are working for the particular patient at specific times.

“The Marginalized Body” (part 2) explores the issue of what Leder calls “embodied injustice.” Drawing on over thirty years of work with incarcerated individuals, he investigates the similarities between the challenges faced by such individuals and the challenges of those suffering from chronic illness. Leder sees that both groups use many of the same coping strategies to survive bodily confinement. He then turns his focus to elders, and explores creative solutions to the last stages of life drawn from cultural traditions around the world, as well as how they might be employed in contemporary America. Given our rapidly aging society, yet our ageist biases and unjust treatment of older adults, exploring such solutions should be an essential concern.

“The Inside-Out Body” (part 3) concludes with an examination of the interconnectedness of bodies with other bodies and with their environment. While examining interoception, breathing, and our body’s sensorimotor system, this concluding section ultimately takes leave of the chessboard of healing metaphor and moves vertically, so to speak, into spiritual dimensions of healing. Leder examines Asian teachings such as Adavaita Vedanta, which advocates dissociation from or transcendence of the body/mind, along with Zen and Taoism with their recognition of the interdependent nature of all phenomena. Sympathetically but systematically, Leder explores the self’s connection to a larger transpersonal universe, perhaps the farthest frontier of existential healing. After all, despite all our efforts, the mortal body will in time grow old, sick, and die. For certain traditions, the realization that we are not just our body is the ultimate healing strategy that relieves our ever-present sense of unease, isolation, and suffering.

Dr. Leder’s final installment in the embodiment trilogy expands the scope of his earlier groundbreaking work at the intersection of phenomenological philosophy, medicine and incarceration studies. In The Healing Body, he carries the analysis even further into directly practical domains of healing. The book is accessible to anyone seeking fresh insight into how to address the challenges of embodied being.

Matthew Swanson, PhD, is an Associate Professor of Philosophy at Misericordia University working in comparative philosophy.